Best Actor, 1997

• Academy Award: Jack Nicholson, As Good As It Gets

Actors win Oscars for playing physically or mentally handicapped characters all the time, but Jack Nicholson’s performance as Melvin Udall in As Good As It Gets is in a bizarre class by itself. In theory, Melvin suffers from obsessive-compulsive disorder: He can’t step on cracks in the sidewalk, for example, and lives his life according to routines from which any deviation inspires panic. He’s also a germophobe, which can be a related condition. Neither of those things, however, ultimately has much bearing on Melvin’s real problem, which is simply that he’s an asshole: boorish, self-absorbed, insensitive, bigoted, etc. Throughout the movie, he does things like shout his order to the wrong waiter across an entire restaurant—nightmarishly rude behavior that has absolutely nothing to do with OCD (though it might have merited an Asperger’s diagnosis, had that syndrome been better known in 1997). Consequently, Nicholson has a lot of trouble making sense of the guy, and tends to lean hard on generic Jackisms, making Melvin one of his signature lovable rogues. (Even when he does impressive work, writer-director James L. Brooks, who seems more insecure than usual about whether the audience is with him, tends to undercut it with formal ineptitude. The famous “You make me want to be a better man” speech, for example, which Nicholson delivers with admirable simplicity and restraint, nearly gets killed by the slow, significant zoom into Helen Hunt’s astonished face that follows it.) This isn’t a bad performance, by any means, but given that Nicholson had already won two Oscars (for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Terms Of Endearment), only something bold and uncharacteristic should have earned him a third, especially in this competitive year. None of the major critics’ groups picked him; they preferred stronger turns in much smaller films. But this was the year of Titanic, and Hollywood largely opted to honor its own.

• New York Film Critics Circle: Peter Fonda, Ulee’s Gold

Who would have imagined, pundits breathlessly asked, that two of the stars of Easy Rider would be still be competing against each other for awards almost three decades later? Fonda’s performance in the earnest Florida indie Ulee’s Gold could hardly be a starker contrast to Nicholson’s showy work; playing a beaten-down beekeeper struggling to protect his family from some remarkably polite but dangerous thugs, he’s as still and gentle as the landscapes visible behind him. Were Fonda even half the natural-born actor his father was, such taciturn underplaying would have been ideal; it’s easy to imagine Henry Fonda (who made Advise & Consent at the age Peter was here) murdering this role. Peter Fonda has always been more of a first-rate camera subject than a performer, though, and his Ulee (short for Ulysses) is sometimes so undemonstrative that he flirts with being bland. Handed a long monologue about the pain Ulee experienced following his wife’s death, Fonda simply recites it, often staring downward as if embarrassed by even the minimal emoting he’s doing. On the other hand, he excels at the numerous scenes that silently observe Ulee performing various mundane tasks involving his beloved bees. Behaving like the subject of a documentary is a specialized skill, which Fonda handles much more ably than delivering the halting dialogue written by director Victor Nunez. If Ulee’s Gold represents the peak of his career, it’s mostly because the film demands so little of him that he’s able to make “not overacting” seem vaguely heroic. Critics went nuts (at least in New York), but it seems significant that this Oscar-nominated performance didn’t lead to a late-career renaissance of any kind; Fonda has kept working, but mostly in tiny roles and/or obscure films. Truth is, his range is exceedingly narrow. Ulee’s Gold works hard to make that limitation a virtue, but it only gets so far.

• Los Angeles Film Critics Association: Robert Duvall, The Apostle

Now here’s some acting. Not since James Cagney barked his way through One, Two, Three in 1961 had the world witnessed such an energetic, tireless performance from a senior citizen. Duvall was 66 at the time of The Apostle’s release, but there’s nothing even remotely creaky about Sonny, a.k.a. The Apostle E.F., a Pentecostal firebrand who starts a new life in Louisiana after killing his wife’s lover in Texas. Duvall clearly studied the cadence of actual preachers, and he nails the rising and falling rhythm—from a bellow to a whisper and back again—that sometimes makes such sermons look like the ranting of a manic depressive. More than anything else, though, it’s abundantly clear how deeply invested he is in this project, which he financed and directed himself after more than a decade of studio rejections. The Apostle is a character study of a deeply flawed but nonetheless worthwhile man—really, it’s about nothing except that man and his improbable journey, which makes it exactly the sort of film that allows a great actor to hit a home run. And while a slightly deranged preacher could easily become a grating caricature, Duvall never allows him to be anything less than powerfully human. Even the scene in which Sonny clobbers his wife’s lover with a baseball bat is played in a unexpected key: The act itself is wholly impulsive, and Sonny doesn’t even seem aware, in the immediate aftermath, that he’s done anything regrettable, as he tries to solicit kisses from his young kids, and only later flees the scene. And give Duvall credit for playing a tender romance with a much younger woman (Miranda Richardson, who’s 28 years his junior) that doesn’t come across as unbearably skeevy. Of that year’s Oscar nominees, he was by far the most impressive; granted, he’d already won… but then, so had Nicholson, and just as recently. (They took home Actor and Supporting Actor, respectively, for Tender Mercies and Terms Of Endearment in 1983.) No excuse, really.

• National Society of Film Critics: Robert Duvall, The Apostle

Here’s Duvall again, so I’ll use this space to briefly address the other two Oscar nominees that year. Everybody remembers Ben Affleck and Matt Damon winning Best Original Screenplay for Good Will Hunting, but I’d completely forgotten that Damon received a Best Actor nomination as well—one of just two he’s received to date, the other being his forgettable supporting turn in Clint Eastwood’s Invictus. This is an unmistakable star-is-born honor, bestowed by people not yet familiar with Damon’s basic moves; looking back at his filmography today, few people would likely be inclined to choose Will Hunting as one of his best performances, rather than, say, Tom Ripley (The Talented Mr. Ripley), Staff Sergeant Sullivan (The Departed), Mark Whitacre (The Informant!), or even LaBoeuf (True Grit). If Damon played Will Hunting for the first time today, it would be received with a collective shrug: cute, charming, not much more. But there was no way to know that at the time, obviously, and the Academy sure liked them apples.

Even more superficially amusing was Dustin Hoffman’s Robert Evans impression in Wag The Dog—another of the actor’s “humping one note on a piano” routines, to quote Pauline Kael’s priceless evaluation of his work in Rain Man. It’s an enormously fun note, though, and Hoffman’s manic energy is infectious; his gesticulations alone arguably deserve some sort of plaque or citation. A stronger case could be made for Mark Wahlberg in Boogie Nights, perhaps, or Al Pacino in Donnie Brasco, or any of the three main actors in L.A. Confidential. But comic performances are so rarely acknowledged at all, much less in the lead category, that I’m not inclined to begrudge this particular choice, if only because Hoffman is having so much fun.

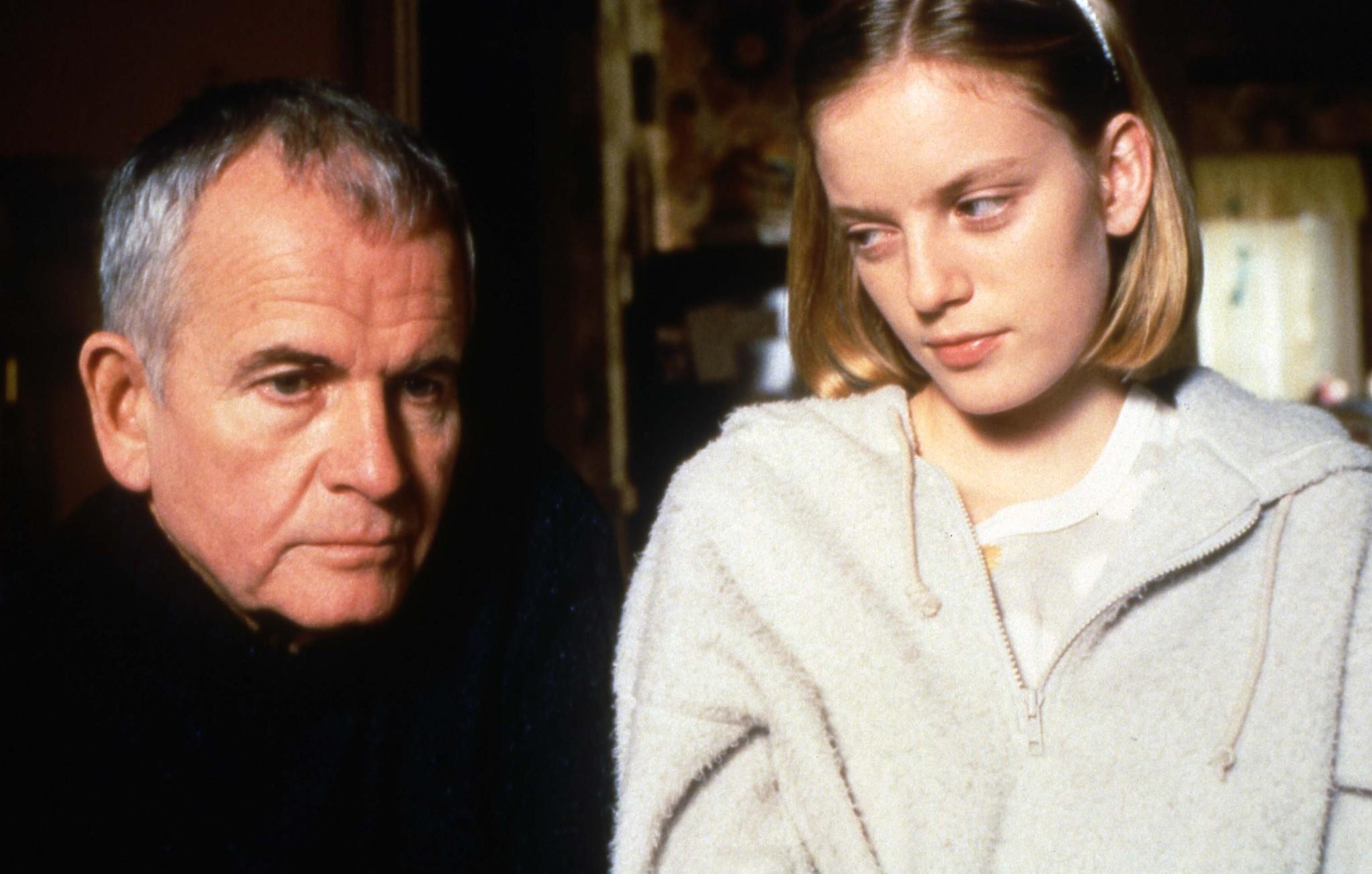

• Performance Review’s Most Overlooked: Ian Holm, The Sweet Hereafter

About midway through The Sweet Hereafter, Ian Holm, playing an unscrupulous lawyer trying to score huge settlements following a tragic school-bus accident, delivers a lengthy monologue about an incident many years earlier in which his daughter, then only a baby, nearly died after being bitten by a baby black widow spider. Director Atom Egoyan shoots the scene in what appears to be a single sustained two-shot of Holm and the actress playing his rapt listener (Stephanie Morgenstern)—though there are some flashbacks interspersed with the story, so it could theoretically be multiple takes—and so powerful is Holm’s quietly impassioned delivery of the story that I’m almost positive he genuinely makes Morgenstern cry at its most crucial moment. (I have never made it through the scene without tears, including just now.) That’s merely the most intimate facet of a truly towering performance, which sees Holm embody craven manipulation, stoic forbearance, wounded dignity, and almost incalculable loss. The ambulance-chaser is usually a cardboard figure in movies, defined entirely by his insulting lack of compassion; Holm, aided by Egoyan’s masterful script and evocative compositions (and Mychael Danna’s plaintive score, too), digs painfully deep into this soul-sick individual, even though the film isn’t really “about” this character in any conventional sense. If I seem unduly dismissive of Peter Fonda above, it’s in part because I’m comparing his work to Holm’s: Both avoid histrionics, but Holm succeeds in conveying the intense passion underlying the carefully chosen words and the impassive demeanor. It’s preposterous that almost no one recognized him that year (save Canada, where he won the Genie for Best Actor), especially since The Sweet Hereafter wasn’t little-seen or universally ignored; Egoyan even received an Oscar nomination for Best Director! “I did not have to go as far as I was prepared to go,” the spider monologue concludes. “But I was prepared to go all the way.” If only.