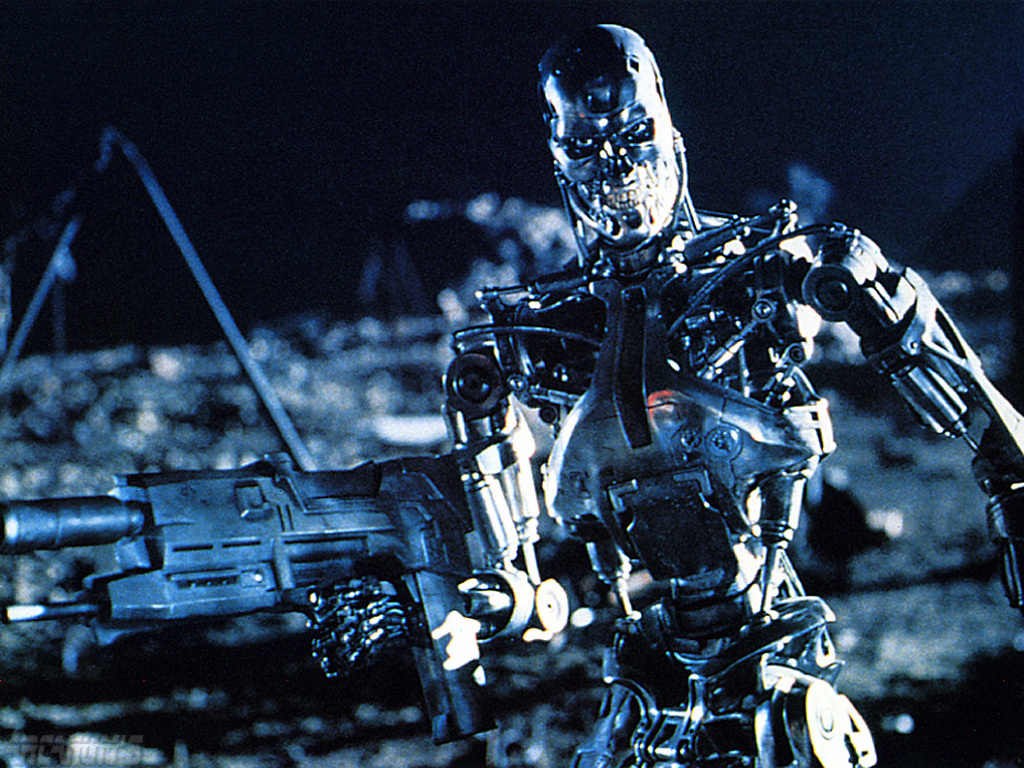

Back in 1984, James Cameron co-wrote and directed a scrappy, relatively cheap $6 million action film called The Terminator, which revolved around an unusually high-concept science-fiction hook: a nigh-unstoppable, futuristic cyborg killing machine, sent back in time to the present day to kill random civilian Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) before she could conceive the son destined to become humanity’s great hope in the robot wars of 2029. The Terminator was a long-lasting hit—not primarily at the box office, where it did reasonably but not spectacularly well for its time, but in the way it entered the cinematic landscape and the science-fiction lexicon. “I’ll be back” and “Come with me if you want to live” became familiar catch-phrases, and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s impassive face—all but expressionless, yet somehow conveying a scowl—became iconic, vaulting him past his previous Conan and Mr. Universe stardom, and on to cinematic immortality.

Cameron went on to write and direct Aliens and The Abyss, each of which had noticeable effects on his next project: his 1991 Terminator sequel, which continued the story by bringing in elements Cameron had originally earmarked for The Terminator. A liquid-metal, shape-changing Terminator was part of his initial script for the first film, but he dropped the idea because the era’s special effects made it impractical. With the sequel—which took the budget from $6 million to $100 million, at the time a record-breaking sum—he brought the concept back, using the CGI morphing techniques he’d experimented with on The Abyss. (“So, raise your hand if you think that was a Russian water-tentacle.”) And he also brought back Schwarzenegger, playing another copy of the T-800 Terminator he’d played in the first film.

The trick is, this time around, the T-800 has a different role. But the film plays out in a way designed to obscure that fact from the audience. In voiceover narration, Sarah Connor (Hamilton again) explains that just as in the first Terminator, the malign future AI Skynet sent an assassin back in time to destroy John Connor—now a 10-year-old, played by Edward Furlong—to prevent him from becoming a future leader. Just as in the first Terminator, Connor’s human-resistance faction sent back a protector to keep him safe. And right up to the moment the two clash, the audience is meant to see Schwarzenegger as the same heavy he played in the last film, and his opposite number, the advanced-tech T-1000 (played in some scenes by Robert Patrick, and in others by a digital effect, which was also groundbreaking at the time), as the hero sent to rescue John.

A variety of clues lead audiences astray. Hamilton’s narration never specifies that the new protector is a Terminator; instead, she implies he’s human by equating this “lone warrior” with the one sent last time—Kyle Reese, the man who became John’s father. When the T-800 first arrives in the present day, his first action is to commit slow-paced mayhem in a roughneck bar, shooting and stabbing the residents and harvesting clothes, boots, weapons, sunglasses, and a motorcycle from his victims. The T-1000 certainly kills the first man he encounters, and takes his police car—but Cameron elides over the details offscreen, never showing the T-1000 changing shape, or making it clear that the cop is dead instead of unconscious. When the T-1000 visits John Connor’s foster home and asks where the boy is, he’s polite and official, where the T-800 was gruff, preemptory, and violent. The newer model appears more human—for all audience members know at that point, he is human. Audiences get to see through the T-800’s eyes on multiple occasions, seeing how he processes the world like a machine, picking options from menus and evaluating humanity solely in terms of threat level and their usefulness to him—for instance, as clothing delivery systems. And most significantly, when the T-800 first sees John Connor, the words “TARGET ACQUIRED” pop up onscreen. It’s no accident that the words aren’t “TARGET TO PROTECT ACQUIRED, BECAUSE I’M THE GOOD GUY THIS TIME AROUND.” Just as Cameron avoids showing the world through the T-1000’s eyes, to reveal that he isn’t human, he’s coyly deceptive about what information he gives the audience even in the T-800’s POV shots.

And none of it mattered, because in 1991, when Terminator 2: Judgment Day was released, the marketing campaign gave the whole game away.

Re-watching Terminator 2: Judgment Day, it’s actually frustrating to see how carefully crafted the first half-hour is, how thoroughly it takes advantage of audience assumptions, all in order to floor them with the big reveal, when Patrick and Schwarzenegger’s Terminators face off over a terrified John Connor, and Schwarzenegger’s is the one who saves John’s life and hustles him to safety. Counting Cameron’s first run at these characters and this basic idea, it took around seven years to build up this fake-out—and just a couple minutes of trailer (and a tagline, “This time he’s back… for good!”) to blow it. It’s one of the dumbest marketing missteps of all time—at least in terms of audience experience.

In terms of actually selling the movie, though, it certainly got butts in seats, to the tune of more than $500 million in box office worldwide, in 1991 dollars. The point of that spoiler-ridden trailer, with its complete lack of respect for the moments Cameron intended as surprises—the reveal that the T-1000 is the villain, the reveal that it isn’t human, the reveal that it can change shape and survive close-range damage from heavy-caliber weapons—was to show just how much of a upgrade this film was from the last one, in terms of scale and ambition, but also in terms of technological developments. Cameron’s attention-grabbing liquid tentacle from The Abyss was stunning to audiences in its day, and the next logical step, an actual character built with CGI technology, was a huge headline-grabber back in 1991. There was no way TriStar was going to leave this ultra-expensive (and eventually Oscar-winning) visual effect out of its sales campaign.

Playing up Schwarzenegger’s role as a good guy was an understandable move, too. His role as the Terminator in the first film was indelible, and audiences wanted to see how a movie monster that heavy could be used on the side of the angels—and what threat could be so monstrous as to give the Terminator a run for its money. It was a perfect role for Schwarzenegger, too, designed with his strength and his limits in mind. Never the most flexible or emotive of actors, Schwarzenegger got the chance to not just be the good guy, but to be the soulful, touching Shane who rides into town and saves the day, then rides back out (in his own modern way), leaving a forlorn child weeping for him. And all this without having to crack a stiff smile himself. For once, the deadpan, square-jawed delivery that’s always been his best comic tool becomes an effective family-drama tool as well. He gets to evoke emotion without having to unconvincingly express emotion himself.

The human element is sometimes the least convincing part of Terminator 2: Judgment Day: Hamilton delivers her already-overwrought voiceovers with maximum leaden portentousness, Furlong’s acting is sometimes clumsy and broad, and the dialogue doesn’t do either of them any favors. The film is built around the spectacle of explosions, destructive chase sequences, and new-to-the-screen effects, and sometimes it’s easy to wish Cameron would get past the explanations and the family-dynamic business, and cut to the action he’s so talented and ambitious at choreographing.

But one of the most compelling elements of both of the first two Terminator movies is the way they balance the machine and human elements, while purposefully contrasting them. Both films take up the idea of how superior unyielding metal seems to soft, vulnerable flesh when the former comes after the latter with malicious intent. But both films also pause to emphasize the warmth of human relationships, and the human elements that give people enough strength to fight off their robot attackers: love, maternal ferocity (borrowed, somewhat, from Cameron’s Aliens), determination, creativity, flexibility, hope for the future. And both focus on human connection, and human moments, in a way that modern action movies often shorthand with a quick scene or two, to the point where the characters get shortchanged. The scenes where Terminators melt through bars or perform motorcycle jumps or just plain blow up everything in sight—those are the exciting moments. But Cameron perpetually keeps his eyes on that soft, vulnerable flesh, and makes sure it gets equal time onscreen, to remind audiences what all the explosions are for.

Terminator 2 is unusual by comparison with modern action films for the way it’s edited, with longer shots and longer takes than today’s films. (More about that tomorrow.) It’s unusual in the way it stands precisely between the age of practical effects and the CGI takeover, with both methods working smoothly together rather than edging each other out. But it’s also unusual in the sheer amount of time it spends watching Sarah Connor navigate her post-traumatic stress disorder, while John Connor deals with his abandonment issues, and bonds with a machine in lieu of the father who died before he was born. Terminator 2 is about a lot of things: nuclear paranoia, the scary side of technology, crafty narrative reversals, the limits of machinery and artificial intelligence, as compared with the human intelligence that created it. But it’s also openly about a weird, temporary, but vital hybrid family, sketched out over long scenes in which each of its three members stretches and grows a little. It was on the cutting edge of moviemaking technology (and moviemaking budgets) in its time, but one of the reasons it still holds up today is the way it’s about more than spectacle.

That’s something that wouldn’t fit in a trailer. Just as well, because the marketers might have found a way to spoil that, too.

Tomorrow our Wednesday Forum continues the T2 talk with a look at the film’s exploitation roots, James Cameron’s queasy relationship with technology, its mix of CGI and practical effects, and more. And Thursday, Chris Klimek concludes with a look at the Los Angeles Police Department as villains, in this film and elsewhere.