Two Dissolve writers keep the Aliens conversation going...

Scott: Maybe the best place to start with Aliens is its conceptual audacity. James Cameron made a sequel to one of the great modern horror movies, and turned it into an action film. In Alien, a single creature took out the crew of an entire space vessel, leaving just Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) standing. Sequels by nature demand an upping of the ante, and multiple aliens perhaps naturally suggest a shift in emphasis from horror to action, but the degree to which Cameron veers in that direction is startling. The ship in the first film is a mining operation, without the firepower to combat an unknown creature whose properties (the parasitic ingestion, the relentless aggression, the acid blood) are only just being revealed to them. The second has Colonial Marines, the badasses of the universe, touching down with the most advanced hardware and weaponry of a spacefaring future era, and Ripley on board to give them intel.

You can see how Cameron and company concluded that Aliens had to be a much different movie from Alien—the premise of a small colony overrun by the aliens requires an escalated response—but what struck me watching it today is how much continuity there is between the two films. Aliens opens with the deep-space silence of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a prevailing element of Alien, where “In space, no one can hear you scream.” And it doesn’t get around to human-on-alien combat until about an hour into its 137-minute run time, choosing instead to establish the situation and give viewers a sense of life on the ship and the key relationships. (And the minor ones, too.) Cameron’s confidence as a storyteller is remarkable, especially from the vantage of 2015, when we’re expecting action beats to arrive a lot sooner. But memories of the first movie—which Cameron brilliantly evokes in a fake-out dream sequence where an alien struggles to emerge from Ripley’s stomach—carry through to a lingering dread before the flamethrowers and grenade guns are busted out. Cameron certainly loves his hardware, but Aliens is not the complete departure from Ridley Scott’s original film that it seems to be. It’s just the next evolutionary step. What struck you this time around, Keith?

Keith: There’s also this connection: Aliens essentially repeats Alien’s ending, on a grander scale. First, it sends Ripley on a last-minute rescue mission as a life-or-death countdown plays out behind her. Then it has her fight an alien aboard the ship she thinks will take her to safety, ultimately blowing it out the (goddamn) airlock. Yet for all those repetitions, it remains a different sort of film. I don’t even know if it’s the next evolutionary step so much as a sidestep. I can’t think of another sequel that so boldly jettisons so much of what made the original work. It’s a risk many aren’t ready to take, but then again, most sequels aren’t being helmed by the ultra-confident James Cameron in the mid-1980s. Not to diminish Cameron now—I’m not the biggest Avatar fan, but he clearly remains a formidable filmmaker—but he was operating on another level at the time, making this movie just after The Terminator, and getting it done on an $18 million budget that was low for big movies at the time, and unthinkable now.

Cameron had a background in special effects, which made him particularly well-suited to this sort of film. I’m sure we’ll get to the effects, but first, let’s talk about the storytelling, which is remarkable. First, there’s the matter of timing. Not counting the dream sequence and the facehuggers in the medical lab, it’s an hour before we get to the aliens in a film called Aliens. (In the theatrical cut, anyway. Which is my preferred cut, in part because we never see the doomed colony of LV-426 until the military expedition arrives there.) Then Cameron packs a nonstop barrage of action scenes into the last 45 minutes, which includes the aliens breaking into the “secure” area, the flight through the air ducts, the kidnapping and rescue of Newt, and the final fight aboard the Sulaco.

Other directors would have spaced all that out. Instead, Aliens takes time to establish Ripley’s woman-out-of-time situation, and the personalities of and relationships between the Colonial Marines, giving a moment of color even to those doomed not to make it through their first encounter with the aliens. It’s a memorable bunch of characters, as Genevieve Valentine addresses, with character arcs and relationships that pay off beautifully, as when Vasquez and Gorman have their moment of understanding as they make their last stand, or when Bishop finally makes Ripley recognize his artificial personhood.

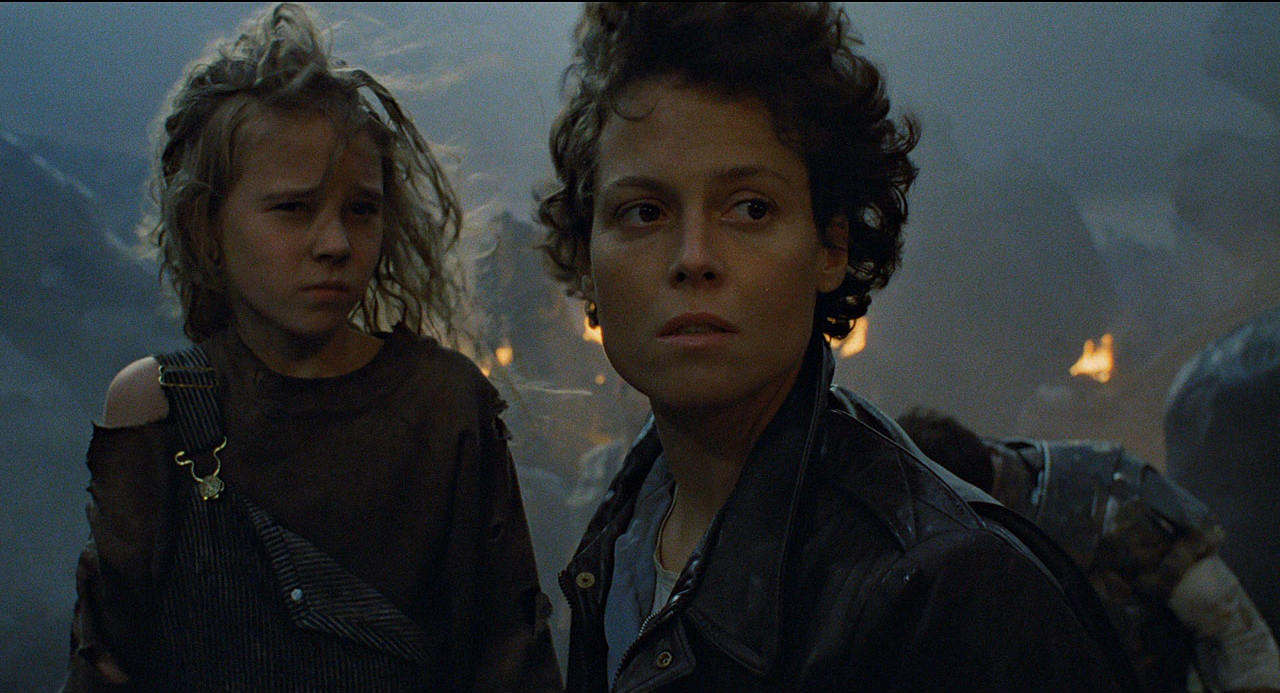

But we’re dancing around the central relationship of the film, between Ripley and Newt, the little girl she rescues from the ruins of the colony. Motherhood is a powerful theme in the movie, with Ripley’s concern for Newt echoed by the alien queen attempting to protect her brood. Let me start by asking you about one detail Tasha brought up in her Keynote: The special-edition cut of the film released in 1992 restores a scene in which Ripley learns the daughter she left behind years before has died during Ripley’s 57-year hypersleep. This establishes a sense of loss to her character, but does it need to? Does the theme play out just as powerfully without its inclusion?

Scott: Initially, no. Ultimately, yes. Waking up after 57 years should be a more powerful moment, given that if the same thing happened to most of us, we’d immediately have to consider the deaths of most of the people we love. (And if Ripley’s daughter hadn’t died, she’d be faced with the odd circumstance of being older than her mom.) After the initial shock, Ripley has to contend with more practical matters of lost time: She doesn’t have the skills or knowledge to thrive in a world that’s gotten away from her by decades. Meanwhile, “the Company” has built a colony of 50 or 60 families on the planet that hosted the alien that wiped out her crew. Much as I’d have loved more details about the future in which Ripley finds herself—how society works, how much power “the Company” wields, how she’s relating to people a few generations’ distance from her—I think it’s smart for Cameron to pare things down to the essential details and keep the story moving forward. As we mentioned before, it takes him plenty of time to get to the action anyway, and Ripley’s grief over her lost daughter would add more freight than necessary.

But long-term, would anyone say Cameron doesn’t hit the maternal themes of Aliens hard enough? I don’t think we need to know about Ripley’s lost child in order to understand and be affected by her relationship with Newt, which can just as easily be chalked up to a material instinct—or plain old empathy. Whatever the case, the bond between them is beautifully realized, mirroring not only the protective relationship between the alien mother and her brood, but the trust that takes time to develop between Ripley and the marines. Like Ripley, Newt has lost everyone she cares about. Also like Ripley, she’s become so self-reliant that she legitimately believes her chances of survival are hindered more than helped by the presence of heavily armed, highly trained super-troopers. Ripley understands her trauma and fear of abandonment, and knows how to instill a sense of trust and safety within a child who sees adults and aliens as almost equally fearsome. Cameron’s ability to thread this subplot into the action is one of the film’s strongest attributes: What parent hasn’t agreed to watch over a frightened child while they’re going to sleep? The nightmare is real in this case—once Company stooge Burke deliberately sets a couple of facehuggers loose in the lab where Newt and Ripley are sleeping—but doesn’t make the maternal gesture less basic or identifiable.

At the same time, Newt is every bit the unlikely badass that Ripley is. I’m reminded of Lillian Gish’s quote from The Night Of The Hunter, another thriller about abandoned and frightened children: “When you’re little, you have more endurance than God is ever to grant you again. Children are man at his strongest. They abide.” What struck you most about the Ripley/Newt relationship, Keith? And what about its alien counterpart? These creatures are simple and vicious, but the maternal relationships have some things in common.

I’d also be interested to hear your thoughts on Burke and his scheming. Though command of the ship goes to Cpl. Hicks (Michael Biehn) after the cigar-chomping Sgt. Apone (Al Matthews) is taken out in that chaotic first ambush, there’s some tension in the film about who really controls the mission. “The Company,” as represented by Burke, has a tremendous amount of power: The colony is theirs, the cutting-edge atmosphere-processor is theirs, and Burke spearheads the effort to recruit Ripley for the mission in exchange for a restoration of her professional rank (and a promise, later broken, to obliterate the aliens). With Aliens, Cameron is predicting, not without reason, that corporations (or one mega-corporation) will have control—or at least a dominant influence—over every facet of human life, from where people live and work to the engagement of the armed forces. Ripley has to argue for Hicks to take over his rightful command, because it isn’t immediately assumed he has it. Burke’s interest in pursuing the company’s agenda—at the risk of his own life, to say nothing of the lives of the crew—is a chilling kind of sociopathy. No mere corporate tool would go as far as Burke does. He doesn’t merely represent the Company. He is the Company, and Cameron invites us to peer into that mentality.

Keith: As Tasha points out, change the perspective a bit, and Ripley’s the bad guy here. Sure, the aliens depend on ruthlessly killing other species to reproduce, but they’re just trying to survive. Part of what makes the finale so powerful is that it plays as a meeting of two beings with similar agendas: protecting the young of their species against anyone who might try to harm them.

As for Burke, it’s one of the film’s neatest reversals to make “artificial person” Bishop (Lance Henriksen) a kind, supportive, distant presence, while making Burke a congenial monster. Burke performs exactly the same function as Ash (Ian Holm) in Alien—forwarding the Company’s agenda whatever the human cost—but he doesn’t have the excuse of faulty programming. The casting of Paul Reiser is ingenious, too. He would soon be a sitcom dad (on My Two Dads) and husband (on Mad About You), but he already had a warmth about him. It’s easy to see why Ripley starts to trust him, if only a little.

On the other hand, it’s not like she has that much choice, if she doesn’t want to spend her days working the docks and her nights smoking cigarettes alone. (Well, with Jonesy the cat.) Weyland-Yutani Corp. is, by all appearances, the only game in town in the future. Cameron doesn’t, as you suggest, spend a lot of time exploring the film’s world, but I think it’s an example of how more can be less. We get a glimpse of life in the future and a hint of conflict between the agendas of Weyland-Yutani and the military contractors they employ, and a lot of suggestions about how exhausting it must be to go on one seemingly pointless mission after another in the Company’s name. (One thing I love about this movie, borrowed from Star Wars, is how scuffed and used-looking the equipment looks.) That sense of space exploration being just another way to earn a buck is carried over from Alien, but here it has the added element of life in the military. The soldiers have had a lot of time to try to find ways to amuse and annoy each other between bug hunts, and not a lot to break up the tedium, despite the occasional colonist’s daughter and the talk of “Arcturian poontang.”

That’s an interesting exchange, right? I don’t want to read Aliens as more progressive than it already is, but it’s interesting the way the Marines joke about how one of them might have gone home with a man, but that it doesn’t really matter if it’s Arcturian. Are Arcturians aliens? A subculture that’s developed somewhere out in space? Whatever the case, it seems like an extremely mild bit of ribbing about sexual confusion that in the actual 1980s—rather than the space-future 1980s of the film—would have been read as much more insulting, and with much more homophobic implications. Maybe I’m overreaching, but it seems consistent with the way the film makes Ripley into an action hero without presenting her gender as a hindrance to kicking ass. Or the way Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein) turns Hudson’s (Bill Paxton) teasing about her butchness back around on him. The smart people know that dwelling on such distinctions, and treating them as limitations, goes nowhere.

Scott: The gender reversals here and in Alien are perhaps just a wish that the future is a more equitable one, and that the roles someone like Ripley can play have broadened considerably. Seeing the marines interact in the lead-up to battle reminded me so much of Starship Troopers, which would come a decade later, and feature a scene where men and women in uniform shower together without issue. That doesn’t stop the full-blown machismo that’s aired in this operation—with Cameron seemingly making up tough-sounding references (“assholes and elbows”?)—including the contrast of Bill Paxton as a hysteric in the face of danger. “Manliness” is still prized in the corps, but men are not its exclusive practitioners; there’s a feeling that Vasquez and Ripley still have to prove themselves up to the task, and they do it by being the toughest of the lot. At the same time, that doesn’t preclude Ripley from taking on the role of surrogate mom. She cannot be confined in the typical masculine/feminine boxes.

So how about a little more praise of Cameron’s storytelling prowess here? He may be dinged fairly for his indelicate touch, especially with dialogue, but his script parses out narrative information beautifully in Aliens. Because Ripley has lost 57 years from her life, it’s completely natural that she would have questions about what happened during the time she missed, but Cameron doesn’t jam the answers into an info-dump. He has Burke deliver the news, and holds off until an official post-mortem on the original mission to reveal, via an off-hand remark, that there’s now a colony on the alien planet. To give you a more granular example, Cameron sets up the big, crowd-pleasing moment (“Get away from her, you bitch!”) by first mentioning Ripley’s job on the loading dock, which then justifies her using a loader to prep for the drop, which then makes it plausible that she’d use the machine for alien head-squeezing purposes. You can also see his work in minor relationships like Vasquez’s intense camaraderie with Private Drake, the last Marine to die in the first ambush. Her anguish in letting him go is one of the most emotionally piercing moments in the film, and it wouldn’t have been possible without Cameron sketching their friendship just enough to suggest their closeness.

Cameron’s wizardry with special effects are less of a surprise here, but nearly 30 years later, Aliens is only a few crude rear-projection shots away from perfection as far as I’m concerned. It’s important that the aliens have a physical presence, so it’s maybe a relief that the film got made at a time when CGI was not available to give form to them. The perpetual darkness of the planet, the colony, and the ship’s environs goes a long way toward making the shape and movements of the creatures plausible, and Cameron emphasizes the visceral mess of contending with them. When Ripley goes down to rescue Newt just as one of the parasite eggs is hatching, the image is somewhere between the stickiness of a spider web and viscous ooze of embryonic fluid. That tactility is the power of physical effects.

So bring us home, Keith. Any favorite individual moments here? And how do you see it in light of future sequels, and as a touchstone for blockbusters to come?

Keith: I tweeted earlier this week that my favorite part of Aliens is every part of Aliens, and that’s not much of an exaggeration. There’s not a scene that doesn’t work, a relationship that doesn’t pay off, or an alien whose appearance doesn’t fill me with terror every time I watch this. And Newt’s cry of “Mommy!” brings a lump to the throat, too, doesn’t it? Aliens arrived at a time when action and science-fiction films were beginning to merge, and the films that first brought them together set the bar high for those that would follow. For that, we primarily have Cameron to thank, with the one-two punch of The Terminator and this movie, but RoboCop wasn’t far behind, and it was another movie that combined science fiction and explosions with some rich thematic material. They also all hit what now looks like a sweet spot for special effects. When we old-timers complain about how CGI lacks the tactility of practical effects, it’s scenes like the trip to the alien nest farm that we’re talking about.

As for the rest of the series, re-watching Aliens made me angry at Alien 3 all over again. There may be no more nihilistic gesture in franchise filmmaking than the way the sequel not only kills off the non-Ripley survivors of the Sulaco, but subjects poor Newt to a fairly graphic autopsy scene. We spent Aliens worrying about her survival and watching her bond with Ripley for that? That said, though the movie has abundant flaws, I respect the way David Fincher attempts to do with Alien 3 what Cameron did with Aliens, by making a substantially different sort of movie than the one that came before. Ditto Jean-Pierre Jeunet in Alien: Resurrection. That one is even less successful than Alien 3, but it’s going for something different. The Alien series defined itself by changing expectations, and even the controlling genre, with each entry. (Yes, I’m intentionally forgetting the Aliens Vs. Predator films.) It didn’t always work out, but it did work brilliantly with Aliens. Other series might take a lesson from it. Sometimes the dares pay off.

Also today, Genevieve Valentine discusses how Aliens set the gold standard for supporting casts. And don’t miss Tasha Robinson’s Keynote essay on the film’s twisted look at motherhood, fatherhood, and other family ties.