Blockbusters have become such an integral part of the way we talk about films that it’s hard to believe they haven’t always been with us. But while there have always been big movies—lavish productions designed to draw crowds and command repeat business—the blockbuster as we know it has a definite start date: June 20, 1975. That’s when Jaws first hit screens in the middle of what was once, in the words of The Financial Times, a “low season” when the “only steady summer dollars came, in the U.S., from drive-in theaters.” It’s summer, after all; why go to the movies when you could be outside? Jaws changed that. Star Wars cemented that change. And now, the summer-movie season is dominated by the biggest films Hollywood has to offer. (At least traditionally; some signs suggest that the season is losing its meaning.)

For our list of the 50 Greatest Summer Blockbusters, we decided to be strict in some ways and lax in others. Only films released in the United States between May 1 and August 31 qualified. That eliminated a lot of films that might have landed on a list of best blockbusters, including the Lord Of The Rings films (all winter releases) and The Matrix (released March 31, 1999). (In fact, only The Matrix Reloaded qualifies for consideration. Spoiler: It did not make the list.) Beyond that, however, we left it open, meaning films with laser cannons and exploding Escalades qualified, but so did animated movies, comedies, and any other sort of film released during summer months. We let the calendar define what it meant to be a summer movie, but let our panel of 12 critics define what made a film a blockbuster, narrowing it down from 655 contenders over the course of three rounds of voting. The process yielded a diverse bunch of movies starting with a comedy about a man discovering love late in life, and ending with… Well, we’ll get to that.

(2005)

One of the funniest movies of the last 30 years (despite being directed with all the visual panache of an episode of The Big Bang Theory), Judd Apatow’s first directorial feature is still his best. The movie runs nearly two hours, and yet it’s harder to think of one joke from the film that falls flat than it is to think of 30 so good they transcend the medium altogether, weaseling their way into the vernacular of friendships and the rhetoric of culture.

When Andy Stitzer (Steve Carell) embarks on a halfhearted quest to have sex (a journey that’s really driven by the transparent projections of his endearingly stunted coworkers), he cemented the foundation for an entire generation of mainstream American comedy, doing for laughter what The Matrix did for leather. Where Wet Hot American Summer covertly introduced a new era of comedy, and Anchorman made a similar brand of absurdity palatable for the multiplexes, The 40-Year-Old Virgin used classic sex-comedy tropes as a trojan horse to marry that silliness to a sense of sincerity. What the film lacks in erotic appeal, it more than makes up for in “Boner Jams.”

The 40-Year-Old Virgin mercilessly lampoons how heteronormative men are disenfranchised from their own desire, but it’s also a gentle slap on the wrists to the legion of movies before and since that hinge on and promote the idea that women are better duped than loved. The film’s moral is that no one should let someone else define their happiness, but everyone should laugh when it happens.

Movie moment

The chest-waxing scene gets most of the attention, and the “You know how I know you’re gay?” banter has probably earned more than it’s worth, but the sequence that best typifies the movie’s sweet alchemy is when Dave (Paul Rudd) takes Andy and the rest of the gang for a round of speed dating on their lunch break. Dave tries to play it cool, but a run-in with his ex-girlfriend Amy (Mindy Kaling) hilariously dismantles all the defense mechanisms he’s been using to protect himself from the fairer sex. (“Remember that time we made love and you just started crying in my arms?”) —David Ehrlich

(2010)

Scott Pilgrim wasn’t the financial smash that many of the entries on this list became; it fizzled at the box office, possibly because audiences were tired of its then-overexposed star, Michael Cera, or because it looks like a movie about videogames, or because it’s based on a beloved indie comic that’s much less known in the mainstream. Theories abounded. But the audiences that failed to flock to the film missed a smart, subversive, funny, and above all impressively dense comedy that uses the visual language of comics and videogames to major effect. In summary, it doesn’t sound like much—it’s yet another story about a loser’s journey to finding himself, getting the girl, and learning how to be less of an ass. But in execution, it’s lively, silly, and tongue-in-cheek in a way that doesn’t undermine its satisfying moments of full-on superhero-movie badassery.

Cera stars as Scott Pilgrim, a wet noodle of a kid who expects his friends to alternately admire and pity him, depending on his mood. When he falls for a stranger named Ramona Flowers (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) and has to fight her seven evil exes for the right to date her, he ends up in a structure straight out of a classic videogame, complete with a boss fight at the end. He also does a lot of flying through the air, smashing through walls, and otherwise defying the laws of physics. The effects in Scott Pilgrim are seamless. In looks, craft, and energy, it fits in with any summer blockbuster on this list. It’s the kind of film that’s destined to keep finding and surprising new audiences.

Movie moment

Some viewers complained about Cera’s version of Scott being limper, whinier, and wispier than the overconfident comic-book version. That’s part of the point. Cera plays the role like a mocking commentary on every other role he’s ever played. But it’s still immensely satisfying when he “gets a life”—in the videogame sense, picking up a 1-UP token that lets him replay his failed actions—and charges back to the scene of his failure, finally understanding who he is and what he needs to do. It’s Edge Of Tomorrow’s death-based learning curve, writ small and hilarious. —Tasha Robinson

(1995)

When people lament that the summer-movie season has become glutted with sequels and licensed properties, squeezing out “original films,” Babe is the kind of original they mean. Based on Dick King-Smith’s slim British children’s book The Sheep-Pig, Babe arrived in 1995 with little fanfare, and took off thanks to word-of-mouth from kids, parents, and cinephiles alike. Writer-director Chris Noonan and writer-producer George Miller turned a sweet tale of a shepherd pig into a funny, moving film about faith, interspecies friendship, and one farmer’s ability to see something special in a runty piglet named Babe.

Today, people generally forget that there was a mini-backlash against Babe when it went from being a surprise summer hit to a surprise Oscar contender, up for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Supporting Actor for James Cromwell’s near-wordless performance as determined farmer Arthur Hoggett. The debate over whether “a kid’s movie” belonged alongside more serious awards-bait presaged some of the arguments today about the popularity of YA literature and superheroes. But Babe is the perfect example to throw back at people who say movies for children are inherently unsophisticated. From the special effects that make real animals “talk” with each other to the eventful story of how Babe earns the respect of real sheepdogs, Babe is a full-course vegan meal.

Movie moment

Babe’s affection for his master is shaken when he learns that humans eat pigs, so Babe runs away. When Arthur brings the sickly Babe home, the ordinarily stoic farmer nurses the pig with a baby bottle, and sings and dances for him. Besides being roughly the third or fourth scene in the movie that reduces the audience to a puddle of tears, Arthur’s song represents what Babe does so well, using quiet, quirky moments to get viewers invested in the more dramatic and triumphant action that follows. —Noel Murray

(1986)

In a grim but entertaining 2011 GQ essay, Pictures At A Revolution author Mark Harris says Tony Scott’s 1986 blockbuster Top Gun was essentially the film that killed filmmaking, and that set Hollywood on a course of craven, self-protective recycling. He blames producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer for turning films into “pure product,” into “rails of celluloid cocaine with only one goal: the transient heightening of sensation.” And he blames the film itself for codifying the kind of blockbuster-oriented thinking that puts marketing, packaging, and demographics above any other consideration. It’s true that Top Gun is a slick, glossy, self-congratulatory thrill-fest, remembered not for its plot so much as for its jet-fighter sequences, three different uses of Kenny Loggins’ “Danger Zone,” and the homoerotic shirtless beach-volleyball scene featuring Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer oiled-up and half-naked. And it’s true that it seems calculated to a T to appeal to young men—as Harris puts it, “16-to-24-year-olds—the guys who felt the rush of Top Gun because it was custom-built to excite them.”

But as shallow as that transient heightening of sensation may be, it’s still a pleasantly intense high, which helps account for Top Gun’s monumental success: It was the top-grossing movie of 1986, its soundtrack has been certified platinum nine times over, it won the Best Song Oscar for “Take My Breath Away,” and its scenes of cocky, swaggering Navy fighter pilots jockeying for superiority reportedly caused a 500 percent uptick in Navy recruitment. Top Gun clearly tapped into something, even if it was just a desire for cocaine in celluloid form, and for Cruise’s glistening torso and blinding smirk.

Movie moment

One moment of plot stands out above the driving music, competitive banter, and fencing conversations that read more like foreplay: The accident that kills one of the main characters. The fatality happens with real-world abruptness and a sickening thunk that momentarily brings the film down to one sharp pinpoint of emotion that’s surprisingly resonant for an action blockbuster. —Tasha Robinson

(2002)

Originally conceived as a sequel to another summer blockbuster spun from a Philip K. Dick short story—Paul Verhoeven’s cruder, bloodier Total Recall—Minority Report proved the perfect platform for a collaboration between Steven Spielberg at his most Hitchcockian and Tom Cruise at his most zealous. Exactly one year earlier, Spielberg delivered A.I., a similarly tough futuristic fairy tale of an artificial boy searching for his mother. Now came the story of a drug-addicted cop gutted by the disappearance of his young son. Set in 2054, Minority Report imagines a future where sunlight and trees and clapboard houses still exist, but privacy doesn’t. The Department of Precrime, which convicts would-be killers based on the prophecies of three semi-catatonic “precogs” (named, cheekily, Dashiell, Agatha, and Arthur), has kept Our Nation’s Capitol murder-free for six years. With the program poised to expand nationwide, Precrime Chief John Anderton (Cruise) is accused of a killing a man he’s never heard of, 36 hours in the future.

The movie’s metaphysical riddle about fate vs. free will gives it substance, but it’s foremost a brilliantly plotted mystery whose marriage of visual and thematic motifs moves as close to Chinatown or Memento as any summer popcorn-seller ever could. Janusz Kaminski’s ghostly cinematography makes it look as though everyone in the frame has already died and ascended to the celestial firmament, unless the entire picture is taking place in purgatory, a distinct possibility. (In the movie’s language, convicts placed in suspended animation are “haloed.”) Though Minority Report was shot before 9/11—a tragedy Spielberg and Cruise later channeled explicitly in 2005’s War Of The Worlds—it was released nine months after. Guantanamo Bay’s Camp X-Ray was open for business by then, giving a chilly resonance to the film’s scenario of people preemptively imprisoned after hasty tribunals via videoconference. The film has also been a startling predictor of technology that became ubiquitous in the years following its release, from touchscreen interfaces to cameras equipped with facial-recognition software. The digital paper and driverless cars? They’re coming.

Movie moment

Forced to go on the lam, Detective Anderton fools the ubiquitous public retina scanners by getting a dual eye transplant on the black market courtesy of Fargo’s sociopath, Peter Stormare, whose nose drips more slime during the procedure than the xenomorph in Alien. “Don’t scratch!” he warns his patient. Later, menacing robotic police “spiders” crawl into the bedrooms of everyone in the building to check the eyes of the panicked residents. —Chris Klimek

(1994)

The Little Mermaid launched the Disney Renaissance, and Beauty And The Beast and Aladdin followed, with each successive movie making significantly more money than the last, to the point where other studios started taking note of the Disney bonanza. But The Lion King was the one that radically changed the field of American animation. Critics dissed the plot as a rehash of Hamlet as filtered through the Japanese anime series Kimba The White Lion, but audiences returned again and again to the film, which made nearly a billion dollars worldwide in theatrical box-office release alone—on a $45 million budget. Suddenly, every serious filmmaking studio needed its own animation wing or production partner; the temptation of that kind of money was just too huge. With one blockbuster mega-success, Disney finally took the revolution far beyond its own walls. Today’s thriving American animated-film industry can be traced directly to The Lion King.

Legacy aside, the film itself is an oddball grab-bag of different tones and beats, from majesty to goofy playfulness to surprising grimness. The pieces don’t entirely fit together—the garish, stylized color-explosion of the musical number “I Just Can’t Wait To Be King” is particularly hard to reconcile with the somber, shocking sequence where lion cub Simba desperately tries to rouse his father’s battered corpse after a fatal stampede—but taken individually, those pieces are on average pretty marvelous. And Elton John’s songs—three of which were up for Oscars, with “Can You Feel The Love Tonight” claiming the win over “Circle Of Life” and “Hakuna Matata”—don’t quite hit the highs of the Ashman/Menken era of Disney, but they’re catchy enough to achieve sing-along status.

Movie moment

Disney promoted the film by releasing the opening sequence, set to “Circle Of Life,” as a teaser trailer. It’s still the sequence that sells the movie: a wonderland of rich, colorful, ambitious animation that culminates in the moment when baby Simba is held aloft, presented to the animals of the veldt he’s destined to rule. The movie opens with a triumphant crescendo that sets the tone for the rest of the story. —Tasha Robinson

(1988)

Bull Durham is the greatest sports movie ever made. Why? Because it runs counter to just about every other sports movie ever made. There’s no triumph over adversity. There are no great rivalries or inspirational moments. There isn’t even a big game—it ends before the season is over. The hero of Ron Shelton’s sleeper hit is “Crash” Davis (Kevin Costner, relaxed and never better), a journeyman catcher for the minor-league Durham Bulls, and it’s one of the film’s many truths that a Big Game ending would be out of place in the farm system. Crash has been tearing it up in the minors for years, but that means nothing, especially for a player too old to be considered a prospect. His actual purpose on the team is to develop the sublimely dopey “Nuke” LaLoosh (Tim Robbins, relaxed and never better), a young fireballer with funky delivery and funkier shower shoes, for The Show. That means lessons on his mechanics (Crash has him wear a garter belt), on talking to the press (“You gotta know your clichés”), and on riding a winning streak.

That last lesson includes not sleeping with Annie Savoy (Susan Sarandon, relaxed and never better), the lovely, learned Bulls groupie who has taken both Nuke and Crash as partners for the season. Once a prospect himself, writer-director Shelton makes observations about minor-league culture that are rich in comic detail, from a meeting on the mound where the guys discuss wedding presents to hilariously misconceived promotional nights. But the love triangle at the film’s center is every bit as good—sexy, romantic, and brimming with intelligence and wit. By discarding the Big Game ending, Shelton arrives at a more satisfying, long-lasting conclusion that’s its own kind of ninth-inning triumph.

Movie moment

Skip past the famous “I believe in” speech—the film’s only bum note, and one Shelton confesses he wrote primarily to attract actors to his debut feature—and there are so many truer nuggets of wisdom in the film, like Crash telling the younger players about the 21 days he spent in the bigs. “You never handle luggage in the show… you hit white balls for practice, the ballparks are like cathedrals, the hotels all have room service, and the women all have long legs and brains.” It’s here that Crash, as much as he’s resigned himself to the journeyman’s role, lets a little regret seep out. —Scott Tobias

(1999)

Brad Bird’s directorial debut was a box-office flop with a blockbuster heart, a financial disappointment whose impact and influence can only be properly appreciated in the context of its failure. With a take of just $23.1 million, the animated wonder didn’t even crack the top 75 highest-grossing films of its release year, yet it’s all but impossible to find an animation buff who doesn’t cite it as one of the medium’s all-time best. Released in 1999, The Iron Giant coincided with the tail end of the hand-drawn Disney Renaissance and the emergence of Pixar’s CGI dominance, and its visuals—presented in glorious, era-appropriate CinemaScope, which Bird insisted upon, despite being warned against presenting tall objects in the super-wide format—bridge the two forms without aping either’s house style.

Bird went on to become one of Pixar’s biggest behind-the-scenes names with The Incredibles and Ratatouille. But The Iron Giant is his signature work: a loving, good-hearted, thoroughly cinematic blend of childlike wonderment and Cold War paranoia, whose embodiment of comic-book superheroism frequently—and deservedly—inspires the laurel “the best Superman movie ever,” even though it featuring a different man of steel. (Well, iron.) But The Iron Giant is more than just homage or a re-imagining; it’s absolutely singular, an unexpected outsider in the animation canon that, like its titular hero, towers above the rest with uncanny grace and humanity.

Movie moment

Sirens blare. A missile streaks through the sky. Our hero takes flight. A little boy’s voice says, “You are who you choose to be.” And then: “Su-per-man.” Not a dry eye in the house. —Genevieve Koski

(2008)

Though it’s hard to believe today, there once was a time when superhero movies weren’t all that common, and films in what would become the Marvel Cinematic Universe were considered risky propositions. Marvel characters had enjoyed great success thanks to the X-Men and Spider-Man series, and proven big business via less fondly remembered films starring The Fantastic Four and others. But those properties were all licensed to other studios, which seemingly left Marvel a little shorthanded when it decided to make its own movies in 2005. Thor, Captain America, The Incredible Hulk, and Iron Man were all characters comics fans had enjoyed for years, but only the Hulk had the kind of broad name recognition enjoyed by Spider-Man, and he was fresh off a not-so-well-received Ang Lee film a few years earlier.

Enter Tony Stark. In retrospect, it’s remarkable Marvel made so many right choices with Iron Man, the first entry in what’s now known as the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but the rightest of all was casting Robert Downey Jr. as Tony Stark, the billionaire playboy industrialist forced by fate to develop a suit of armor suitable for the 21st century, and maybe beyond. Downey is effortlessly charming in the role, but also skilled at conveying the gravity of any situation in which his Stark finds himself, offering glimmers of panic as he quips about his predicament. He’s exactly what the films needs him to be: the big-screen embodiment of the complicated, troubled heroes that set Marvel’s comics apart from the competition. Downey and a cast that included Jeff Bridges and Gwyneth Paltrow in a film helmed by actor/director Jon Favreau emphasize the drama, letting the story lead and the effects, as impressive as they are, follow. It’s a fleet, entertaining film that feels substantial, no matter how loud the explosions.

Movie moment

One of Iron Man’s best moments comes relatively early, when Stark, under duress, develops his first primitive suit while being held captive in a cave. To escape, he fudges what he’s up to, then turns the suit against the captor. It’s a thrilling sequence, and one that defines the character through action: He uses muscle and firepower to win, but only because he’s able to use his brains first. —Keith Phipps

(2013)

Director Edgar Wright and his co-writer/stars Simon Pegg and Nick Frost conclude their Cornetto Trilogy, which started with the zombie comedy Shaun Of The Dead and continued with the action-movie parody Hot Fuzz, with an alien-invasion tale that’s as much a critique of blockbusters as a stellar example of one. As two in a quintet (Martin Freeman, Paddy Considine, and Eddie Marsan play the others) of middle-aged men who return to their hometown to complete the pub crawl they couldn’t finish as teenagers, Pegg and Frost discover their old haunts have been “Starbucked” into bland, colorless, neutered homogeneity. And as the evening wears on, they discover the people are as conspicuously hive-minded as the bars. It’s hard not to see The World’s End as a metaphor for pop culture—and by extension, the movies themselves.

Like Wright’s other work, The World’s End is something of a shadow blockbuster, both in the sense that Wright is making these crowd-pleasing entertainments on a smaller scale, and that he’s doing it with the wit, intelligence, and flavor that’s been Starbucked out of Hollywood tentpoles. (Hence the mass anguish over his exit from Ant-Man, suggesting Marvel’s failure to jam this particular square peg into a round hole.) While The World’s End is fun, however, it’s also a sobering, acutely observed portrait of middle age, built around Pegg’s performance as a long-in-the-tooth 40-year-old desperately clinging to the past. There are still robot invaders to fight in high style, and a barrage of boozy one-liners exchanged between friends, but it’s the rare summer movie that’s trimmed with melancholy.

Movie moment

The embarrassing spectacle of middle-aged men attempting “The Golden Mile” comes through when Pegg and his chums arrive in town and strut toward the first leg of the journey. Wright shoots it with Reservoir Dogs cool, putting Pegg in the middle with a black leather coat and sunglasses, with lots of rebel attitude. Then the gang pass a group of kids less than half their age, heading in the opposite direction. It’s clear which ones are the sad poseurs. —Scott Tobias

(2001)

Baz Luhrmann directed films before his musical Moulin Rouge! (Strictly Ballroom, Romeo + Juliet) and afterward (Australia, The Great Gatsby), but while virtually all of his projects share a dizzying, psychedelic fascination with libertines and libations, none of his other films have put his visual signatures and specific obsessions to such perfect use. Moulin Rouge! is garish and broad in its story of a penniless writer (Ewan McGregor) in love with a beautiful—and expensive—courtesan (Nicole Kidman) who’s coveted by a scheming duke (Richard Roxburgh), but Luhrmann is entirely conscious of his own campiness, and thoroughly embraces it. Jim Broadbent, playing a procurer with a heart of gold, embodies the film’s lunatic spirit, howling and booming his way through setpieces built around repurposed, familiar pop songs. His wild, deliberately over-the-top rendition of Madonna’s “Like A Virgin,” delivered to convince the dangerously jealous duke that his love object is pristine and untouched by any underhanded penniless writers, is simultaneously a manic highlight and a shameless low point.

Movie moment

Kidman’s character, Satine, is introduced with a joyous but pointed rendition of “Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friends,” a show-stopping number illustrating the glitz and glamour of fin de siècle Paris and the Moulin Rouge cabaret, and laying out its money-talks-and-romance-walks philosophy. The film’s biggest flourish, though, comes when Satine, dying beautifully and operatically of tuberculosis, sends her lover away for his own safety, and reprises that theme song to open the play he wrote and the duke funded. The reprise, “Hindi Sad Diamonds,” turns Kidman into a glittering, emotionless clockwork icon in the midst of a madly extravagant Bollywood setting. Onstage, surrounded by servants, wealth, and intensely elaborate rococo décor, she appears to have everything a courtesan could want, but it’s all cold and mechanical without the love she felt forced to reject. —Tasha Robinson

(2009)

Generally, animated children’s films don’t start with 10-minute montages about infertility, disappointment, and the loss of a soulmate. But Pete Docter’s Up is all about baggage. Aging widower Carl Fredricksen (voiced by Ed Asner) spends a big chunk of the movie lugging his house—a metaphor for the memories of his beloved dead wife, Ellie—across a South American mountain. Letting viewers experience the full scope of Carl and Ellie’s marriage from giddy young love to heartbreaking goodbye gives viewers their own emotional baggage to tote around through the film, and helps them understand why Carl goes to such extreme lengths to get to Paradise Falls, the place Ellie always wanted to visit, but never could.

When Carl and Ellie first met as children, they both idolized Charles Muntz (Christopher Plummer), a disgraced explorer famous for searching Paradise Falls for a mythical monster in his giant dirigible, the Spirit Of Adventure. And as Carl finally lets go of his dead wife’s memory and embraces life again, Up is filled with its own spirit of adventure, with Carl becoming the protector—first reluctantly, then proudly—of a host of lovable sidekicks: awkward but enthusiastic Wilderness Explorer Russell (Jordan Nagai); gangly “monster” bird Kevin; and Dug (co-director Bob Peterson), a dog who can speak through a high-tech collar, when he isn’t distracted by the sight of squirrels.

Up is Pixar’s most whimsical, inventive blockbuster. There are aerial dogfights between planes piloted by actual dogs, and swordfights on blimps thousands of feet in the air. (The vertiginous 3-D photography also made Up one of Pixar’s most spectacular theatrical experiences.) The film doesn’t ever surpass its transcendent opening, but that’s sort of the point. Life for Carl will never be what it was with Ellie. But if he can let go of his pain, it can be good again.

Movie moment

The opening montage that takes Carl and Ellie from little kids to senior citizens. The entire thing is told silently; everything is expressed though gestures, camera movements, and Michael Giacchino’s wistful score. The sequence offers one indelible image after another, from the montage of neckties that mark the passage of time to the moment when Carl floats a dying Ellie a message strung from a balloon, in an echo of the night when they met as kids. If you can watch this scene without crying, it’s time to consult your optometrist, because there’s something wrong with your eyes. —Matt Singer

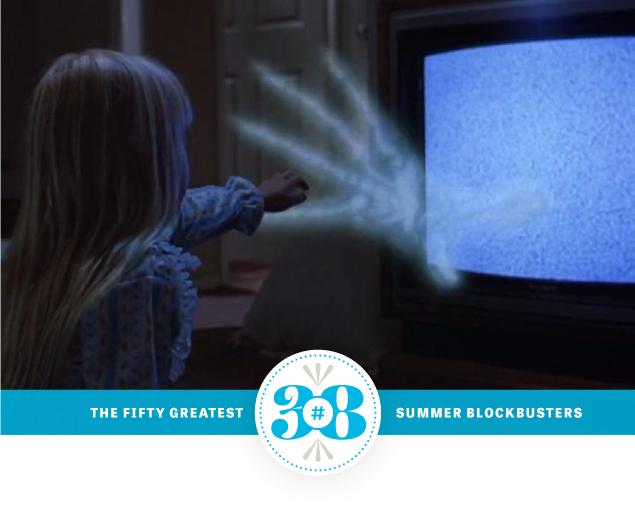

(1982)

In 1982, Poltergeist punched a hole in the world of happy, homogenous American suburbia, and during a Steven Spielberg-dominated summer movie season, provided the dark counterpoint to the rainbow streak of light that was E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. Tobe Hooper received the official director’s credit on Poltergeist, but it’s Spielberg—who co-wrote and produced—whose tone dominates this portrait of a California family shaken by the spirits of those buried six feet under their kitchen linoleum.

One of Spielberg’s greatest assets is his ability to understand children, a skill that manifested gracefully in E.T. and via sheer horror in Poltergeist. As the movie’s tagline promised, Spielberg knows what scares viewers: that gnarled tree outside the bedroom window; the unfinished backyard swimming pool that could turn into a mud pile of decaying corpses; static-filled TV screens that communicate messages from kids kidnapped by the dead; scary-ass clowns that come to heart-stopping life. (There’s no hard data on this, but it seems to fair to assume there was a huge spike in the number of clown dolls immediately destroyed after Poltergeist was released in June of 1982.)

But what makes Poltergeist a great summer blockbuster isn’t its frightening imagery or jumpy moments, though those are well-executed. What makes it an enduring horror movie is the the way the film eases into its chills and bonds the audience to the Freeling family. When Carol Anne announces, “They’re here,” it’s disturbing, because it’s such an ominous note for a little girl to strike. But it’s also disturbing because every young suburbanite feels like she could be right there in Carol Anne’s place, placing her defenseless hands on a glowing television that will soon become her only conduit to home.

Movie moment

Diane Freeling’s climactic rescue of Carol Anne and the film’s nightmarish finale are the most obvious highlights. But look again at the scene in which Beatrice Straight’s Dr. Lesh explains why some spirits rest in peace and others don’t. That exchange—and the poignant way Robbie says good night to his sister by talking to the TV—confirms that this isn’t just a ghost story. It’s a story about real people struggling with the specter of death. —Jen Chaney

(1982)

When a Paramount executive suggested to novelist-turned-filmmaker Nicholas Meyer that he take a meeting about the second Star Trek picture, Meyer’s response did not inspire confidence: “Is that the one with the guy with pointy ears?” Scrimped together for only a quarter of Star Trek: The Motion Picture’s runaway budget, The Wrath Of Khan, for which Meyer also wrote the shooting script (uncredited, and for free), was the cheapest Trek and by far the richest, replacing its precursor’s cosmic torpor with a swashbuckling tale of high-seas adventure that just happened to be set in outer space.

But the movie had soul, too. Meyer didn’t initially know Mr. Spock from Dr. Spock, but he loved C.S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower novels, and he decided that borrowing their nautical milieu would be the key to making his silly space movie something that wouldn’t embarrass him. He made now-Admiral Kirk’s fear of aging and obsolescence a key theme. He turned the U.S.S. Enterprise, which had always felt like an intergalactic Howard Johnson’s, into something more like a submarine, cramped and dangerous. And he quoted Moby Dick, literally and figuratively. Returning to the 1960s Trek TV show to resurrect Ricardo Montalban’s Khan—a brilliant but crazed product, in Star Trek’s future-past, of the “Eugenics Wars” of the, er, 1990s—Meyer gave the character a self-annihilating lust for vengeance against Kirk, who exiled Khan and his crew to a once-fecund-but-now-barren planet after foiling their attempt to hijack the Enterprise. Though Khan and Kirk never meet in the movie (except via viewscreen), Montalban’s operatically unhinged performance secured Khan’s place as the Trek-iverse’s greatest villain.

Khan was also memorable for the ship-saving death of Spock, a natural climax for a story about Kirk coming to terms with mortality. After test audiences balked, Meyer suggested Leonard Nimoy—who was coaxed back for the sequel with the promise of a grand death—recite the TV series’ famous “Space, the final frontier” narration at the end to acknowledge that Spock would live on in memory. But the tag scene of Spock’s casket on the surface of the “Genesis Planet,” suspiciously intact, was appended over Meyer’s objections.

Movie moment

After a quick meeting with Kirk, young Lt. Saavik (a pre-Cheers Kirstie Alley) complains to her mentor, Spock—in subtitled Vulcan—that the admiral “always seems so human!” Spock responds with Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond’s kicker from Some Like It Hot: “Nobody’s perfect.” —Chris Klimek

(1984)

For a stretch in the 1980s, Steven Spielberg became a kind of industry unto himself, directing huge movies and serving as a prominently billed producer on even more. It seemed like he brought in directors to express parts of his personality sublimated in his own movies: Horror expert Tobe Hooper for Poltergeist, Richard Donner for the juvenile adventure of The Goonies, Robert Zemeckis for the comedic Back To The Future, and so on. Spielberg enjoyed a long relationship with Joe Dante, one that often involved Dante offering visions from an alternate Spielberg universe dominated more by black comedy than wonder. This habit stretches back prior to their professional partnership with Dante’s quick-and-nasty Piranha, a variation on Jaws, and up to the Dreamworks era, when Dante’s goofy Small Soldiers appeared side by side with Spielberg’s earnest Saving Private Ryan, military tales with a different slant on duty, honor, and sacrifice.

Released two years after E.T., Gremlins plays a bit like that film’s evil cousin. Everything’s just a little bit off: In place of Spielberg’s suburbia, Dante offers Kingston Falls, a small town that’s a barely disguised backlot. Like E.T., it features an adorable creature, but one whose introduction has consequences never visited upon Elliott and his family. Fed after midnight, its adorable mogwai turn into the horrifying gremlins of the title, creatures hellbent on destruction, and on turning Kingston Falls into a living Mad magazine parody of some half-forgotten horror movie from Dante’s youth.

It’s graphic enough that, along with Spielberg’s Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom, it inspired the MPAA to create the PG-13 rating just for such ’twixt-and-’tween movies. And while it’s unfair to write the movie off as a goof—it’s genuinely scary, and Dante had to fight to keep a memorable scene in which Phoebe Cates’ heroine recalls a grim Christmas—Dante’s punkish instincts to spray graffiti over movie-perfect Americana set it apart. The good guys win in the end, but Dante shares more than a little sympathy for the gremlins. (For further evidence, check out the gleefully anarchic 1990 sequel Gremlins 2: The New Batch.)

Movie moment

Helping the good guys win is a late-film distraction in the form of Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs, which the gremlins watch, transfixed in a cozy theater. In Dante’s world, and Spielberg’s, such is the power of movies. —Keith Phipps

(1989)

Comic-book characters had flown across movie screens since the 1940s, and Richard Donner’s Superman proved conclusively in 1978 that movie audiences would believe a man could fly. But it was Tim Burton’s Batman that invented the modern superhero movie by ditching the genre’s stereotypical trappings of spandex and sidekicks in favor of gothic atmosphere and a dark, brooding hero. When Burton made Batman, comic-book movies were still largely thought of as B-level exploitation pictures for children, done quickly and on the cheap. When Batman became the No. 1 movie of 1989—topping established franchises like Back To The Future, Ghostbusters, and Indiana Jones—it proved the viability, both creatively and financially, of superhero stories on an epic scale. With Batman, Burton didn’t just create a movie, he created a world: a Gotham City of nightmarish architecture, and a seedy underbelly teeming with crime.

The film’s impact cannot be overstated. In Batman’s wake, its logo became one of the most iconic and marketable images in all of popular culture, adorning T-shirts, posters, and even the backs of a few poorly parented children’s heads. Hollywood responded by churning out a series of glossy imitators, all designed to ape Burton’s retro-pulp vibe and hyper-stylized setting. But these Bat-knock-offs lacked Burton’s secret weapons: Danny Elfman, whose stirring compositions matched Burton’s dark visuals; Anton Furst, visionary production designer of Burton’s Gotham (who committed suicide in 1991); and actors like Jack Nicholson, whose penchant for onscreen madness was rarely more suited to a role than that of the Joker, and Michael Keaton, who nearly matched Nicholson in deranged intensity. Their moonlit dance with the devil was a thing of hideous, world-changing beauty. Blockbusters would never be the same.

Movie moment

It’s all about the big showdown between Batman and the Joker at the parade the latter has supposedly thrown to prove his awesomeness to the people of Gotham (but has actually thrown so he can kill everyone with poison gas). As Joker attacks, Batman swoops in with his high-tech jet, the Batwing, snatches the villain’s toxic balloons, and flies away. He releases the balloons, then soars above the clouds, pausing for one moment in front of the moon—creating a giant spontaneous Bat-logo in the sky. It’s an unforgettable image. No wonder kids started carving it into their hair. —Matt Singer

(1982)

In retrospect, The Thing probably shouldn’t have been presented as a summer blockbuster in the first place. John Carpenter’s masterpiece hit theaters on June 25, 1982, where it promptly bombed. The $15 million horror film, a mercilessly nihilistic monster movie that boasts more sociopolitical allegories than female cast members (at least two and almost one, respectively) and takes place at a frigid research center in the middle of the endless Antarctic tundra, opened to a whopping $3.1 million, placing it eighth at the box office behind a murderer’s row of classic pop spectacles like E.T., Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan, and Blade Runner. But we all know how this story goes: The film froze over and waited for a rescue team of critics to rescue and reappraise it, and when The Thing finally thawed out, it was unstoppable.

Adapted from John W. Campbell’s novella Who Goes There? by Bill Lancaster (son of Burt), the film is quickly suffocated by the dread of its premise. There’s exactly one scene of levity before the shit hits the fan, a chuckle-worthy bit of foreshadowing in which bored helicopter pilot MacReady (Kurt Russell) is checkmated by a computer chess machine. The joke isn’t that MacReady has been defeated by an imitation, but that the movie has just started, and he’s already lost. Everyone has. The Thing has all the dramatic uncertainty of The Death Of Mr. Lazarescu, but Carpenter’s genius is that he’s able to keep the best of both worlds, already mourning his indelible characters while he’s still mining suspense from their circumstances.

It’s ironic that a film so fondly remembered for Ennio Morricone’s unsettling electro trill is defined by its silence. The snowdrifts muffle the sound and vacuum-seal the research base, which—in concert with Carpenter’s camera, slyly orienting viewers to the layout of the station—cultivates the sickening sense that, in Antarctica, no one can hear you scream. And in the darkest recesses of all that emptiness, a threat in waiting begins to take a number of increasingly gruesome shapes. Rob Bottin’s amazing creature effects are so good, they almost leave an odor, but it’s easy to forget how much of the film’s terror is mined from the invisible and the unseen. Steeped in Cold War paranoia (“Thing” also being the name of a Soviet listening bug) and set during the year that AIDS was officially named, The Thing immaculately traces the fine line between hope and extinction, becoming one of the few films as scary as the ideas it invokes.

Movie moment

It’s not the blood test, which is a classic Russian-roulette situation, cooked to perfection. It’s the chest-paddles, as Norris’ rib cage suddenly gives way to a row of enormous teeth that chomp Copper’s arms clean off. It’s the way the bodies shake and vibrate when the Thing affects them, and how the snapping ligaments in Norris’ neck are inexplicably green. And it’s definitely Palmer’s “You gotta be fucking kidding,” saying what everyone else is thinking as Norris’ detached head begins to sprout legs and groan like a dying Wookie. —David Ehrlich

(1983)

Here’s a fun bit of trivia: If you watch the 25th-anniversary Blu-ray of Risky Business on a large enough television, you can actually see the hormones wafting in the air like the heat waves of a boiling Chicago summer. No movie before or since Paul Brickman’s classic has so teased and tapped into the erect id of the heterosexual American teenage boy, conditioning an entire generation of horny young men to have a Pavlovian response to the ethereal synth beats of Tangerine Dream.

But if Risky Business owes its massive box-office success to teen boys, and its nostalgic appeal to the star-making performance of a young Tom Cruise as Joel, slathered in a fresh layer of cherubic fat, the film’s enduring value can be attributed to the fact that it isn’t just about horny high-school boys, even though it so fluently speaks their language. Brickman’s surprisingly inclusive intentions are signaled by the extended first-person sequence in which Joel’s parents read him the riot act before they leave him their house for the weekend. The camera transforms the bourgeois nagging (what kind of asshole cares that much about an ugly glass football?) into a one-size-fits-all attack. This isn’t about sex so much as it’s about freedom, and the economic pressures of the Reagan era.

But it’s still totally about sex. It lets Cruise look at Rebecca “What every white boy off the lake wants” De Mornay’s Lana with his mouth hanging open, without ever losing sight of how easily lust can be exploited. Joel and Lana are roughly the same age, but she’s much older. From very different starting points, they arrive at the same sex-positive place together. And that’s why the movie is still so much fun: because it captures that feeling of how everybody needs a little excitement. Joel’s relationship with Lana isn’t believably sustainable even in the upbeat ending the studio forced upon the movie, but it doesn’t really matter. He has his memories, he lived a little, and that’s what every white boy off the lake really wants.

Movie moment

Don’t even with that Bob Seger scene. Sure, Tom Cruise sliding into frame in a pair of tighty-whities was the moment that launched the career of our greatest contemporary movie star, but it doesn’t even begin to compare with the el-train ride that launched a million teenage boys into puberty. Joel, fresh off a successful night of converting his parents’ house into a pop-up brothel, is dragged into the city by Lana, who “wants to make love on a real train.”

And so begins a sequence that contains not one, but two of the greatest music cues in film history. Phil Collins’ “In The Air Tonight” is practically a plot song here; written about the anger the singer felt after divorcing his wife, the song’s lyrics and its orgasmic build to that drum fill couldn’t more perfectly capture the do-or-die anticipation of teen sex if they tried. And then, as Joel removes a drunken hobo from the train car, the synth majesty of Tangerine Dream resurfaces. Here, of all places, is the birth of Wong Kar-wai, beautiful bodies entwined and stuttering in step-printed slow-motion, the moment born immediately into memory. And then there’s that spark. —David Ehrlich

(1980)

Cinephiles justifiably mourn the loss of the Western and the musical—once-flourishing genres that now produce maybe one picture every few years, if we’re lucky. Pour one out as well, though, for the fast-paced, gag-based comedy, which today exists only in the form of such abominations as Date Movie and the Scary Movie franchise. Once upon a time, there was ZAZ: David Zucker, Jim Abrahams, and Jerry Zucker, who collectively turned sustained silliness into an art form. Airplane! was their masterpiece, employing the template of a forgotten 1957 drama called Zero Hour! to poke incessant fun at the then-popular Airport series, along with any other random topic that sprang to mind. No idea was too ridiculous, yet there’s a sophistication underlying the anarchy, epitomized by the casting of actors with fairly grave personas—Leslie Nielsen, Robert Stack, Lloyd Bridges—who were encouraged to play everything perfectly straight.

Airplane! has such a high GPM (Gags Per Minute) that 10 different people might fondly recall a dozen favorites apiece and have little or no overlap. There’s visual humor, like the hero’s “drinking problem,” which involves his inability to get liquids into his mouth. There’s verbal humor, like the pilots’ vaudevillian cockpit chatter. (“We have clearance, Clarence.” “Roger, Roger. What’s our vector, Victor?”) There are parodies of other movies, though these deftly avoid the modern-day pitfall of coming across like nothing more than checklists of iconic scenes, slightly tweaked. And there’s the eternal question “Joey, have you ever been in a Turkish prison?” Surely you remember that especially creepy running gag. [Your indignant reply here.]

Movie moment

Again, there are so, so, so, so many to choose from, making the task nearly impossible. So here’s one selected almost at random: Robert Hays’ Ted Striker buying his ticket for the doomed airliner, being asked by the agent whether he prefers smoking or non-smoking (remember, it was 1980), answering “smoking,” and promptly being handed a ticket that appears to be on fire, billowing smoke. He accepts it without a second glance, heading for the gate. That’s how you do goofy. —Mike D’Angelo

A Fish Called Wanda

(1988)

The surprise mega-hit of 1988, this modest comedy (and previous Dissolve Movie Of The Week) is fairly close to being a perfect film. The heist plot is exciting, the characters are colorful, the dialogue is memorable, and the cast is perfectly suited for their roles. Kevin Kline won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his energetically nimble portrayal of a dumb but pretentious American thug, but the rest of the cast—Jamie Lee Curtis, John Cleese (who also scripted), Michael Palin, Tom Georgeson, and Maria Aitken—also hit their comic beats flawlessly, turning what could have been a broad comedy into a tightly tuned humor engine. This is a movie that casually gets away with letting a character kill three small, fluffy dogs while trying to murder their owner, all without losing its light sense of play, or even losing the audience’s sympathy for the dog-assassin.

A lot of the credit goes to Cleese’s script, which is absurdist and outrageous, but keeps a propulsive enough plot, full of betrayals and counter-betrayals, to support all the nonsense. The real question of the story isn’t who will end up with the stolen diamonds that provide the film’s McGuffin, but who will survive all the treachery and attempted murder, and more significantly, whether Curtis’ sharp-eyed schemer will get away with playing everyone against each other to her own benefit. Viewers were so taken with Charles Crichton’s snappy direction and the film’s comic density that they boosted the $8 million film to a $100 million box-office payday.

Movie moment

There are dozens of infinitely quotable lines in Fish Called Wanda, and most of them come with memorable moments. But one scene in particular stands out for the way it sums up the film’s dynamics. Stuffy but sad British barrister Archie (Cleese) has spirited manipulative femme fatale Wanda (Curtis) off to a borrowed vacation home for a tryst; she’s using him to get information on some stolen diamonds, but all he knows is that a beautiful, lively American girl has taken an interest in him. Half-dancing around the lower level of their love nest, stripping for sex and reciting Russian poetry to excite Wanda (who gets so turned on that she starts humping the furniture), Archie is stark naked and giddily spinning about with his own underwear on his face when a British family walks in the door, having just rented the flat. As the rest of the scene plays out, with Archie just-barely covering his danglies with a hastily snatched portrait, it’s worth noting that he’s exposed, awkward, and humiliated because he finally expressed his emotions, while Wanda is safely out of sight and gets off scot-free. That pattern repeats throughout the movie, always to wry comic effect. —Tasha Robinson

Tomorrow: Our countdown continues with numbers 30 through 11. Then on Thursday, we’ll reveal our top 10, with extended pieces on each.