Damien Chazelle still isn’t 30 years old, and he’s written and directed a Sundance sensation. Whiplash, his second feature film (after 2009’s black-and-white indie jazz musical Guy And Madeline On A Park Bench), won the Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award in the Dramatic category in Park City earlier in 2014, and a significant Oscar buzz has followed it ever since. It’s easy to see why: The film is a sharp, electric story, stylishly told and rivetingly performed. Miles Teller (Divergent, The Spectacular Now) stars as Andrew, a talented up-and-comer at a terrifyingly competitive all-male music school considered the best in the country. When he attracts the attention of Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons) and gets a spot in Fletcher’s jazz band, he thinks his potential has been recognized, but Simmons abuses his charges mercilessly in an attempt to bring out the genius in any who don’t break under the pressure. After playing a long run of snappish but benign cranks in films from Juno to Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man run to the Coen brothers’ Burn After Reading, Simmons reaches back to the much more dangerous tone of his long-running white-supremacist villain on HBO’s Oz. He’s a mesmerizing force of intimidation and fury in the film, and his clashes with his students are literally breathtaking, in that Chazelle ramps up the tension—and the speed of the film’s many jazz-band performances—until it’s difficult to breathe. The film is heavily inspired by Chazelle’s own experience as a high-school drummer with an abusive mentor, and his struggles with anxiety and depression during that period of his life. The Dissolve recently sat down with Chazelle in Chicago to talk about how he made the film, and how he means people to take it.

The Dissolve: You’ve said that part of the impetus behind Whiplash was processing your own high-school band experience, and trying to resolve the clash between “Music should be fun!” and “Artistic greatness is worth any cost.” Did you reach any conclusions in writing or shooting the film?

Damien Chazelle: That’s a really interesting question. I guess no. I guess it’s still something I’m not sure about. If you’re going to play music or do any art form, just as a hobby or as purely a source of enjoyment, then yeah, you should enjoy it. But I do believe in pushing yourself. If you actually take the idea of practice seriously—to me, practice should not be about enjoyment. Some people think of practice as “You do what you’re good at, and that’s naturally fun.” True practice is actually about just doing what you’re bad at, and working on it, and that’s not fun. Practice is about beating your head against the wall. So if you’re actually serious about getting better at something, there’s always going to be an aspect of it that’s not fun, or not enjoyable. If every single thing is enjoyable, then you’re not pushing yourself hard enough, is probably how I feel. But this movie takes it to a extreme that I do not condone. [Laughs.]

The Dissolve: The summaries of the film I’ve seen in different reviews certainly suggest people are taking Fletcher differently. No one is fully on his side—

Chazelle: “He’s so misunderstood!”

The Dissolve: But some reviewers describe him as a monster, and some as a cruel but necessary teacher, citing what Andrew accomplishes under his watch. Did you intend for Fletcher to be ambiguous?

Chazelle: Yeah, because I think that’s the question posed by a lot of these tyrannical teachers, tyrannical band leaders, tyrannical directors. To what extent is it the tyranny pushing people, and to what extent is it other stuff? I personally think fear is a motivator, and we shouldn’t deny that. Someone like Fletcher preys on fear. I think there’s a reason his methodology sometimes works, both in real life and on the screen. Fletcher’s methodology is like if there was an ant on this table, and I wanted to kill it, so I used a bulldozer. Yeah, you kill the ant, but you also do a lot of other damage. And in Fletcher’s mindset, that’s actually fine. Fletcher’s mindset is, “If I have 100 students, and 99 of them are, because of my teaching, ultimately discouraged and crushed from ever pushing this art form, but one of them becomes Charlie Parker, it was all worth it.” That’s not a mentality I share, but in many ways, that’s the story of the movie. He potentially finds his Charlie Parker, but he causes a lot of wreckage in that pursuit.

The Dissolve: The film seems more ambiguous as it’s in progress—it feels like it could become a Full Metal Jacket situation, with revenge on a destructive bully, or an inspirational-teacher movie, or something else entirely. Were you thinking in terms of keeping people guessing about the ending?

Chazelle: Yeah, one thing I definitely wanted people to wonder is whether Andrew is going to basically kill himself drumming, like the old fairy tale of the dancer who dances herself to death, or [Edgar Allan Poe’s] “The Oval Portrait,” where the painter kills his subject by painting her. The idea of art being something that kills is weirdly fascinating to me. Especially toward the end, I definitely wanted to film Andrew in a way that looks like he’s this close to literally having a heart attack and keeling over. I wanted people to worry not just for his sanity, but for his physical well-being. There’s a physical side to this instrument, and a brutality that’s not just emotional, but corporeal.

At the same time, I like genre movies, and this fits pretty squarely into the sports-film genre. You’re building up to the big fight, or the big game. In this case, it’s the big performance. There are certain kinds of narrative rules in terms of how you do that, where you have to bring the character really low before you bring them high, and you have to do another microcosm of that within the big fight. Even if they’ve had their low point, you can’t just have them show up to the climax and immediately knock the guy out. You still need to have another mini low point. There are narrative rules that you don’t have to follow, but I actually thought since this is not a sports movie, they would be fun to follow. It gave me the leverage to wholeheartedly embrace some of those tropes.

The Dissolve: Were you thinking of specific films in terms of that plot map?

Chazelle: A lot of boxing films—The Fighter, Rocky—but I think in terms of the road map and the moment-by-moment feeling I wanted to capture, it was much more the the non-sports-movie sports movie, which is Raging Bull. It’s a sports movie, but really not.

The Dissolve: Women in those movies are virtually always support networks, or objects that get shunted to the side. Your romantic subplot in Whiplash seems like it mostly exists to reveal Andrew as arrogant, as thinking of himself like a smarter version of Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull, determined to avoid the same pitfalls. Was there more to that subplot?

Chazelle: To me, it was funny to spend enough time on a supporting character where you’re like, “Okay, we’re spending time with this person, so this is going to become a storyline that really carries through,” and then cut it off earlier than you expected. I thought it was also weirdly indicative of Andrew’s state of mind that he has this whole speech to this girl, where he basically purports to know everything about her, and her hopes and dreams, when we’ve literally seen them go on one date. Maybe they’ve gone on a couple others that we haven’t seen—that’s left ambiguous—but certainly they’ve not been a couple for a long time. He purports that he can just sit down and X-ray into her. And that, to me, was really him becoming a mini-Fletcher. Fletcher has a single conversation in a hallway with Andrew, then decides he knows his entire backstory, and knows exactly how to twist the knife. It’s a subjective movie, so you have to stay in Andrew’s point of view, but hopefully in terms of how that scene was staged, it clues the audience in to the fact that Andrew is not the only person in the story, and his actions actually have consequences on other people.

The Dissolve: You get a little into drum esoterica in the film, and you’re dealing with such complex rhythms that I suspect the average viewer can’t tell whether the drummers are actually doing anything wrong when Fletcher calls them out. Did you think in terms of making that accessible to viewers? Is it all just in the actors’ reactions?

Chazelle: I think it doesn’t matter. I was just the other day watching, probably for the 50th time, David Fincher’s commentary track on The Social Network. He talks about the Facemash scene, and why he loves procedurals, and how that relates here. There’s sometimes this fallacy in movies that you have to understand what people are doing. If people are at work, you have actually spell out to the audience what they’re doing. In his mind—and I agree with this—that actually doesn’t matter at all.

“I think there’s a difference between making something exciting and explaining it.”

The only burden on you is to convince the audience that the people onscreen know what they’re doing. That to me is more exciting. I like to watch people at work who are clearly more knowledgable about the work than I am. I almost like to feel a little lost. I like that when I’m watching Mark Zuckerberg do Facemash that it’s going a little quicker than I can follow, so I’m getting a broader picture, but if you ask me to go do what he did, I would’t be able to do it. That, to me, is part of the fun of movies. They should be able to shine a light on a subculture or profession or discipline that we’re not familiar with, and make it exciting. I think there’s a difference between making something exciting and explaining it.

The Dissolve: To some degree, just the speed at which he’s drumming suggests to laymen that he’s doing well.

Chazelle: Yeah. I mean, we could have done a whole movie where they’re all playing ballads, and he’s just playing with brushes, but then I think the movie would be interesting to musicians and myself, but not to other people. Certainly, part of the thinking at the outset was, “What kind of music are we going to do?” Most of the music in this movie is a specific kind of jazz. It’s fast, aggressive big-band jazz that’s very drum-heavy: numbers that really feature the drummers in a prominent way. That immediately gives an energy you can build from, and that dictates the cutting style, the shooting style. That type of music is so frenetic and hectic and violent in a way, it was really just a matter of shooting to keep up with it.

The Dissolve: I’ve read that Miles Teller did almost all of his own drumming, that he was a drummer already, but didn’t know anything about jazz drumming, and you and other people had to teach him that for the film. Did you have to visually cheat around anything in terms of his ability?

Chazelle: Much less than I thought. Certainly, one thing I should clarify—he did pretty much all of the visual drumming onscreen, but the audio of the drum solo at the end is mostly not Miles. He’s not actually the greatest drummer on planet Earth. [Laughs.] But he learned how to seem like he was the greatest drummer on Earth. It’s all about visual tricks. It’s about doing stuff that looks difficult, but isn’t that difficult. As a drummer myself, I knew what those things are. Piano’s the same thing. It’s really easy for pianists to do fast arpeggios, and people look at it and go “Wow,” but it’s still actually easy. As a drummer, it’s pretty easy to do fast stick work, and spin around, and do stuff that’s really fast, or do over/underarm stuff. There are just certain kinds of things you can do that look impressive.

Ironically, some of the hardest stuff Miles had to do in this movie was just some of the beats. Not even the drum solos. Just the beat to “Whiplash” is really hard. That’s a beat that actually sounds easier than it is, because it’s in a weird time signature, and it’s just fucked-up. We did a few weeks with him at the drum set, just crash-course training on specifically what he would have to play in the movie. And he was so good on set that we almost never had to use a double. There’s a couple of things here and there where there’s a close-up on his hands, or the top of his head, where it’s a double. But even stuff where you normally would use a double, like really wide shots, or shots of his back, or quick pan shots where we could get away with a double if we needed to, it’s actually Miles. I was pretty impressed on set. He really brought it. Even a good 40 percent or so of what you hear on the soundtrack is live audio from him playing on set. He did a good job.

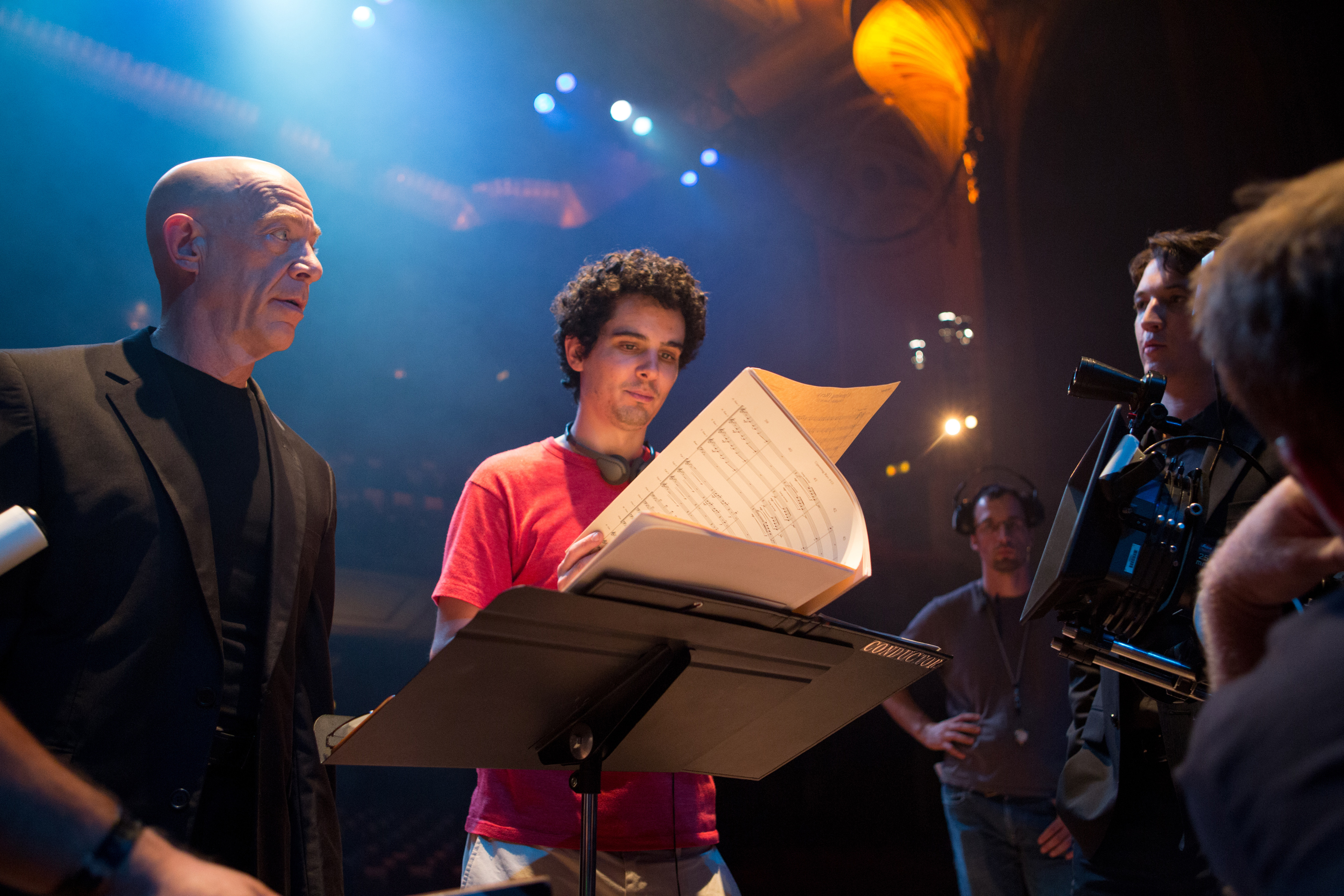

The Dissolve: What was your directorial work with J.K. Simmons like? How did you coach him, or how much did you coach him?

Chazelle: I didn’t have to coach him much. He went to music school, so he knew how to conduct. He has a degree in conducting. [Laughs.] He knew that world, and he also had such a conception of the character that he was just lifting off from what I had on the page—the wardrobe, the physical appearance, that was all him. It’s so fun to work with an actor who just makes you better. An actor who takes what you’ve written, or what you’ve conceived, and fully realizes it. He’d go on set, we’d do a take. I would make some minor adjustments. We’d do another take. It was all just a matter of minor shifting. The fundamentals were all there.

The Dissolve: He’s unusually visually striking in the film—he’s always in black, he wears very tight T-shirts, you focus in on his biceps. I had no idea he was that bulked-up.

Chazelle: Yeah, it was important that he feel like a person who could beat the shit out of you if he felt the need. He actually makes very little physical contact in the movie, but the threat is always there. Miles is a big guy himself. Miles is actually a lot taller than J.K., which is funny. With J.K., there’s almost an aerodynamic shape, with the shaved head. I joked it was like Fred Astaire goes to Parris Island. It’s like this cross between a dancer and a military drill sergeant.

The Dissolve: The homophobic insults Fletcher uses are an early tip-off that maybe his character isn’t so ambiguous, maybe he is just a dick. Why was that necessary? What did you want viewers to get out of his language?

Chazelle: It is precisely that. It’s that to me, his behavior is not tough love, it’s not ambiguous, he’s not this grumpy guy whose rubber ducky was stolen, so he decided to… There’s nothing redeemable in him. Certainly I think his passion for the music is admirable, and sometimes he gets results, which is admirable, but there’s nothing admirable about the behavior. A lot of that is just pulled from history, what jazz-band leaders have often done. They haven’t exactly been models of progressive politics.

The Dissolve: You’ve said you came under pressure to tone things down in the film. Was it that kind of language? Or more about the physical violence?

Chazelle: No, it was the language. Specifically, the language of hatred. When Fletcher uses anti-Semitic or homophobic language. But it was part of the point, to me. There’s not a single demographic group in existence that he doesn’t go after at some point in the movie, but there’s almost no logic to it. I remember one person commented on the point where he starts yelling at one of the drummers, using homophobic language, this commentator assumed the drummer was gay. Maybe he is, maybe he’s not, but that doesn’t matter to Fletcher. He’s in a room with a group of highly competitive, undersexed, workaholic musicians who are all stepping on each other to get one of the two or three spots available for them, so he’s going to use the kind of language—it’s the same thing you see in military boot camp—that makes them feel as un-masculine as possible. There’s something so reactionary about him. Especially in the context of music like jazz, which we like to think of as not a reactionary art form. But I think jazz is a lot more full of cruelty and hatred than we think. It doesn’t make that art form any less great, but I think we should not be blind to what the world is like.

“I think jazz is a lot more full of cruelty and hatred than we think. It doesn’t make that art form any less great, but I think we should not be blind to what the world is like.”

The Dissolve: It’s fascinating when you show Fletcher actually playing jazz himself. He does have skills, but he doesn’t have the drive or aggression he has in training. You just said he wasn’t someone who got his rubber ducky taken away, but did you have a backstory in mind in terms of his history as a musician?

Chazelle: J.K. and I talked a little about it. We never spelled it out. I think he thought initially that he would go into musicianship, and I think pretty early on, realized that he was like Salieri in Amadeus, in that he was good enough to know who’s better, and that his real skill lay in sniffing out the Mozart when no one else could. He’s not a genius player. He’s a nice player, and he has skills. That’s not actually what he gives his heart and soul to. He gives his heart and soul to watching other players, and trying to push them to something.

The Dissolve: Do you generally think there’s any truth to, “If you can’t do, teach?”

Chazelle: J.K. and I talked about that. No, I don’t really believe that. I think what it is is that it’s almost two different art forms, in the sense that there’s the art of actually performing the music, but there’s also the art of teaching. Same as there’s the art of making something, and there’s the art of criticism or analysis. I really don’t buy that notion that there’s an art form, and everyone who surrounds it are the people who couldn’t cut it. I think that denies how all the people around that art form are equally important to that art form. Jazz and any art form would not progress as quickly as it did without the teachers, the critics, the champions, the historians, the patrons, producers. It’s all part of the same equation.