Early in Tim Burton’s movie Big Eyes, an aspiring artist named Margaret Keane (played by Amy Adams) takes a job at a furniture factory, where she paints small Humpty Dumptys on headboards, using her artistic talent to help fill bulk orders. Later, she does the same for her husband Walter, producing paintings that he sells under his own name. Over time, Margaret isolates herself, and ends up locked away in a succession of upper rooms, alone and misunderstood.

Burton didn’t write Big Eyes, but Margaret is very much a Tim Burton character. Heck, she may be Tim Burton.

Burton was born in Burbank, California, in the heart of the entertainment industry. He was reportedly a quiet kid who kept to himself, more interested in art and popular culture than in school. After studying animation at the California Institute Of The Arts, Burton went to work for Walt Disney Productions, like a lot of Cal-Arts grads. He joined up at a time in the early 1980s when the studio’s animation department was at a low creative ebb. Initially bored and disillusioned with having to spend his days cranking out sketches and cells for other people’s films, Burton eventually found a few like-minded artists who encouraged him to experiment on the company’s dime. The work he did at Disney was good enough to get him work as a feature director—a career that got off to a fast start with the surprise 1985 hit Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure and the left-field 1988 smash Beetlejuice.

As a director, Burton quickly established a style and a set of themes. Half Steven Spielberg and half David Lynch, Burton has often made dynamic, crowd-pleasing movies about people a lot like himself: misfits adrift in pleasantville. Over and over, Burton has borrowed from spooky old movies and kitschy TV shows to tell stories where losers become winners by beating away bullies in noisy final battles that take place in tall, shadowy towers. His early films in particular are obsessed with darkness, though by the end, nearly all of them round off any sharp edges, leaving audiences more reassured than challenged.

Yet whatever Burton’s work has lacked in real danger, it’s more than made up in visual splendor. Over time, Burton has relaxed some of the anti-normalcy posturing of his early work, and has been willing to acknowledge that being an upstanding family man has its merits—to the extent that a lot of his later films sometimes become borderline-cloying. But Burton hasn’t relaxed his restless camera, or his preference for elaborate, unusual movie sets. Few filmmakers have ever been as consistently inventive as Burton.

Few have been as frequently frustrating, either. Over the past 15 years, Burton has often taken assignments that seem motivated more by money than by any personal connection, and he’s courted self-parody by working with a lot of the same people over and over, including his wife, Helena Bonham Carter; his friend Johnny Depp; and composer Danny Elfman, whose cartoonish, Carl Stalling-inspired scores are a major part of what makes a movie “Burton-esque.” But never let it be said that Burton doesn’t put his own stamp on his work. Even when he’s just painting Humptys on cribs, Burton has a perspective—and a rare gusto.

Short Stuff (1982-1984)

| 5 | “Vincent” | 1982 |

| 2.5 | “Hansel And Gretel” | 1983 |

| 3.5 | “Frankenweenie” | 1984 |

| 3 | Faerie Tale Theatre, “Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp”: Season 5, episode 1 | 1986 |

| 2.5 | Alfred Hitchcock Presents, “The Jar”: Season 1, episode 20 | 1986 |

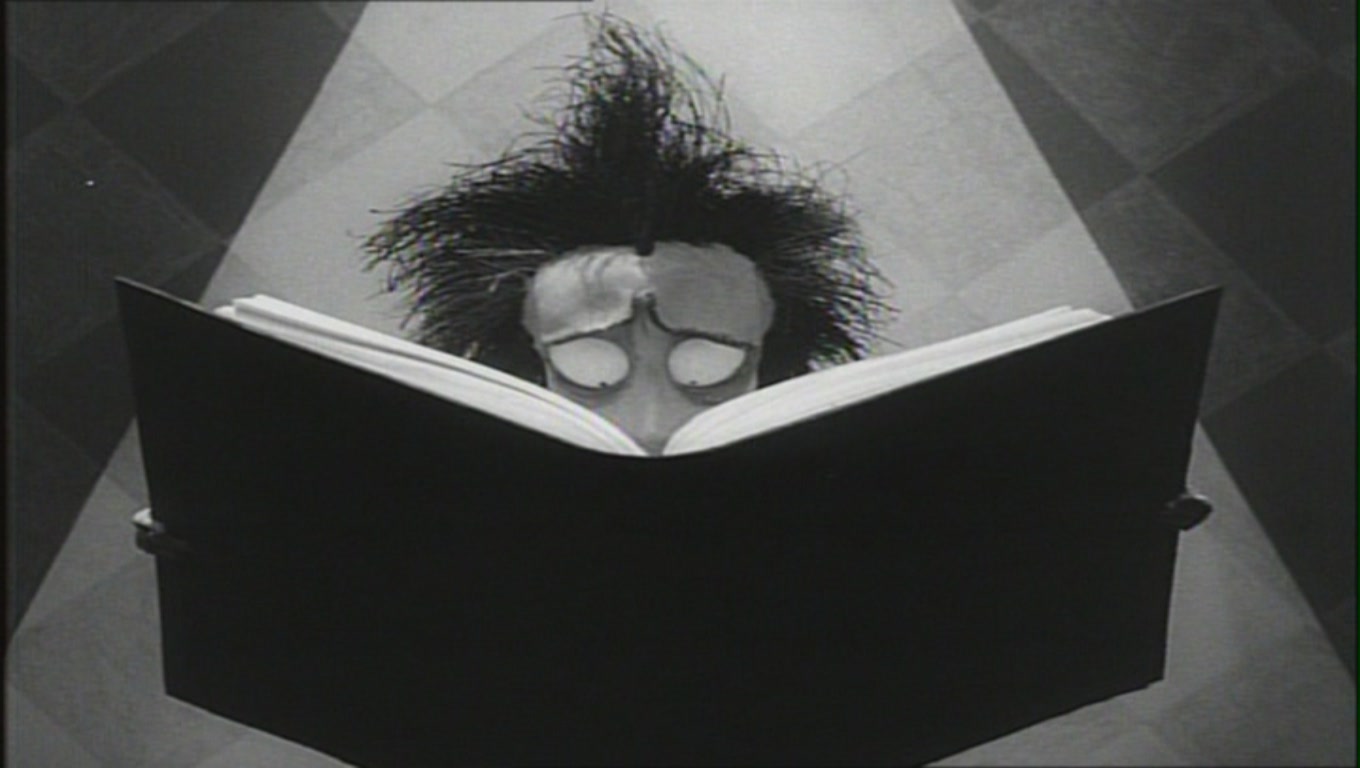

Tim Burton has only made two perfect films in his career, and one of them is less than six minutes long. While working for Disney, Burton wrote and directed the stop-motion short “Vincent,” about a little boy obsessed with Vincent Price. Practically a thesis statement for Burton’s entire career, “Vincent” calls back to classic Hollywood in the narration (by Price himself), and has a style and rhythm that recalls both Dr. Seuss and Chuck Jones. The film is a thank you of sorts to the artists who inspired Burton, revealing through jump cuts how their way of seeing the world transformed his own. What’s most striking about “Vincent” is the way Burton keeps contrasting the young hero’s bland home-life with the shadowier world he wishes he were inhabiting. Here, at ground zero for Burton’s filmography, he makes his first confession that he maybe isn’t as weird as he wants to be.

There wasn’t much of a market for a film like “Vincent” back in 1982, but the short did prove that Burton could be useful to Disney, if the studio pulled him off feature animation and let him play. His next project for the company was a half-hour Disney Channel special: a live-action adaptation of the Brothers Grimm’s “Hansel And Gretel” that Burton and screenwriter Julie Hickson set in Japan, making the story seem more exotic. The special has a soft, slow, twinkly quality—a little like an extended segment from Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood. It’s too remedial to engage adults for more than about a minute at a time, but any given one of those minutes is a treat to look at, filled with puppets, overtly artificial sets, and charming mechanical gadgets.

The next short film Burton made for Disney was his last: “Frankenweenie,” another half-hour live-action film, about a boy named Victor Frankenstein who brings his dead dog back to life with an electrical jolt. Given how obviously uncommercial “Frankenweenie” was in 1984, it’s surprising how many resources Burton was given to make it. He got Daniel Stern and Shelley Duvall to play Victor’s parents, and shot the movie in beautiful black and white on a sunny suburban set that looks like a leftover from a 1950s sitcom. Like “Vincent,” “Frankweenie” slips gothic-horror trappings into the unlikeliest of settings, revealing the world of Burton’s youth the way he always wanted it to be: populated by dimwitted neighbors who chase well-meaning mad scientists into the tallest structures in a crumbling miniature-golf course. Burton and screenwriter Lenny Ripps have a hard time sustaining this premise for a full 30 minutes, but the film is clearly the work of a director with a unique slant, mixing freakiness with sweetness.

Disney had no idea what to do with “Frankenweenie”—at least until after Burton became famous, after which the studio released it on home video—so he and the studio parted ways. If he’d been cut loose a year or two earlier, maybe Burton could’ve made “Frankenweenie” for one of the anthology TV series the networks were trying out at the time, like Amazing Stories, the new Twilight Zone, and the new Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Instead, Burton ended up doing some work for those shows after launching his feature career. He collaborated with his old Disney colleague Brad Bird on the animated Amazing Stories episode “Family Dog” (later developed into a short-lived CBS series, co-produced by Burton and Steven Spielberg), and for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, he directed “The Jar,” an adaptation of a Ray Bradbury short story about an unsuccessful artist who obtains an ugly artifact that mesmerizes people. The episode has a Danny Elfman score and a screenplay co-written by Beetlejuice co-writer Michael McDowell, but it’s largely devoid of Burton’s style or wit. It’s most useful as a thematic precursor to later Burton films like Ed Wood and Big Eyes, showing how even the worst junk can be captivating.

There’s a lot more of Burton in “Aladdin And His Wonderful Lamp,” an episode of Shelley Duvall’s Showtime series Faerie Tale Theatre that Burton directed in 1986. Robert Carradine plays the crafty Aladdin, who gets his genie (James Earl Jones) to help him win the love of a princess (Valerie Bertinelli) and thwart a rogue (Leonard Nimoy). Though shot on video, Burton’s “Aladdin” looks as opulent as a big-budget movie, with colorful costumes, impressive makeup effects, and sets that sport Burton’s familiar kinks and curlicues. Two years after making the intermittently stilted “Frankenweenie,” Burton had learned a lot about pacing. He gives this episode a lot of zip, like a 1980s sitcom with no laugh track—not even any pauses for laughs. Burton and screenwriters Mark Curtiss and Rod Ash show a particular fascination with the Genie, painting him as an unstable, dangerous individual who threatens terrible violence, then emits a booming, unconvincing “I’m just kidding” laugh. The Genie in Burton’s “Aladdin” is the living embodiment of Burton’s early aesthetic. He’s also one of Burton’s most tragic characters: a perpetual servant who admits, “I have great powers, but very little imagination.”

| 5 | Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure | 1985 |

| 4.5 | Beetlejuice | 1988 |

| 3 | Batman | 1989 |

| 4 | Edward Scissorhands | 1990 |

| 4 | Batman Returns | 1992 |

Unlike the Genie, the Tim Burton of the mid-1980s was a man with a surfeit of imagination, but very little power. Then Paul Reubens—the performance artist known to the avant-garde comedy world as “Pee-wee Herman”—saw “Vincent” and “Frankenweenie,” and asked Burton to help him make a movie that was already in development at Warner Bros. Pee-wee’s Big Adventure is Reubens’ movie, dropping his man-child character and his Saturday-morning kiddie-show sensibility into a picaresque plot (co-written by Phil Hartman) that sees Pee-wee making new friends across America while trying to retrieve a stolen bicycle. But Pee-wee’s Big Adventure is very much Burton’s movie, too. It’s his other perfect film, after “Vincent.” Working in the tradition of visually oriented comedy directors like Jacques Tati and Frank Tashlin—while copying neither—Burton puts Pee-wee and his handmade props inside a well-lit, well-decorated frame, reveling in the artificiality of it all. There’s a reason Pee-wee’s Big Adventure became a cable-TV staple and go-to video rental in the 1980s. It’s so packed with good-spirited gags and strange interludes that it never goes stale. (There are too many classic bits in the film to name them all, but the coda where Pee-wee has an awkward cameo in the movie version of his own story is particularly funny and playful.) The movie has a satisfying arc, too, as Pee-wee leaves the comfort of his own home and comes back wiser—and even a fraction more mature.

With Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, Burton showed Hollywood that he could make the outré into mainstream fare. But because Hollywood wasn’t teeming with Pee-wee Hermans in the 1980s, it took three years for Burton to find a project he could make his own: Beetlejuice, an offbeat supernatural comedy written by horror novelist Michael McDowell, then rewritten by Warren Skaaren. Alec Baldwin and Geena Davis star as a genteel married couple, the Maitlands, who die in a car accident and come back as ghosts. When they try to rid their house of the artsy New York family that’s just moved in, the Maitlands get frustrated with afterlife bureaucracy and go for a shortcut by calling on Beetlejuice, an obnoxious corpse played by Michael Keaton. Beetlejuice goes full Woody Woodpecker on them, though, introducing more anarchy into the situation than the Maitlands can handle. The movie’s rickety story structure is just sturdy enough to let Burton make what amounts to a 90-minute live-action cartoon, piling on slapstick, blackly comic sight gags, and cheap, handmade special effects. Beetlejuice is a movie for the world’s model-builders and moody loners who feel overwhelmed and overlooked. Beginning what would become a recurring Burton motif, the Maitlands are invisible to everyone save the New York family’s goth daughter (played by Winona Ryder), the only one cool enough to see what’s special about them. Beetlejuice also kicks off what would be nearly a decade of movies wherein a misanthropic Burton could barely conceal his desire to drive out “infestations by the living.”

During the years between Pee-wee’s Big Adventure and Beetlejuice, when Burton was suddenly the hottest new director in Hollywood, he started developing the movie that would become the 1989 blockbuster Batman—though he didn’t get the final green-light from Warner Bros. until after Beetlejuice. At the time, some comics fans questioned whether a director with a style as broad as Burton’s was a good fit for the late-1980s era of the “grim ’n’ gritty” superhero, and Burton didn’t quiet their concerns when he cast comedic actor Michael Keaton as his caped crusader, and grizzled Jack Nicholson as his maniacal Joker. Burton’s Batman is a lot campier than the Alan Moore and Frank Miller comics he claimed as his inspiration. It’s also the first Burton feature that feels compromised by studio demands: It sports rote action sequences, jarring Prince songs, and a Nicholson performance that pushes Keaton to the margins of his own movie. But there’s a lot of Tim Burton in the picture, too—primarily in the way he and cinematographer Roger Pratt explore Anton Furst’s grimly imposing Gotham City sets, scratching beneath the surface of the superhero movie to find Fritz Lang and film noir.

Post-Batman, Burton wasn’t just an A-list director, he was one of the few working directors in the U.S. who had an identifiable style, much like Spielberg and Lynch. Taking advantage of his moment in the spotlight, Burton chose not to jump right into a Batman sequel, and instead returned to an idea he’d been kicking around for years, about a suburban outsider with scissors for hands. The 1990 fantasy Edward Scissorhands became another Burton hit, which either says something about how the ticket-buying public was growing accustomed to Burton’s kinks, or proves that he’s never been as kooky as he’s presumed. Either way, Edward Scissorhands is one vibrant, clever movie, with a bruised heart. Johnny Depp makes his first appearance in a Burton film, playing the title character: a mad scientist’s creation left to rot in a spooky old house after the old man (Vincent Price) unexpectedly dies. Edward is rescued by an Avon Lady (Dianne Wiest) and taken to live in a nice middle-class neighborhood, where he’s first looked on as a fascinating curiosity, and then as a menace. The simplistic plot arc is already something of a retread for Burton. It takes a lot from “Frankenweenie”—right up to the climactic clash in a dark tower—and too often, Caroline Thompson’s script goes for cheap laughs at the expense of Edward’s square neighbors. But there are moments where Burton lets Depp express real pain at how he’s alienated from the culture around him. And Edward Scissorhands earns its heartstring-tugging ending by gradually revealing how having someone like Edward around makes everything more beautiful.

With Edward Scissorhands finally out of Burton’s head and onto a screen, he was free to pay another visit to Gotham. But he came back on his own terms. Batman Returns is the Tim Burton movie he didn’t get to make the first time: a film filled with angry freaks. This time, Keaton’s Batman is plagued by The Penguin, a misshapen orphan (Danny DeVito) abandoned by his wealthy parents. He’s also bedeviled by Catwoman (Michelle Pfeiffer), a former milquetoast office worker who gets pushed too far and becomes a righteous, steal-from-the-rich feminist. And everyone in the movie has to deal with corrupt industrialist Max Shreck (Christopher Walken, doing his best Christopher Walken impression). Even more like a 1940s crime picture than the first film, Batman Returns offers relentlessly slam-bang action—to an exhausting degree—couched in Burton whimsy. Whether it’s Catwoman threatening Penguin by putting a live bird in her mouth or Penguin employing an army of actual armed penguins to do his bidding, the movie takes ideas that could’ve looked silly and puts them in service of a grand vision. Gotham City in Batman Returns is a place where the powerful and powerless are equally scarred, and pushed to fight each other in the sewer for control of the hellscape above. Next to Sweeney Todd (made during a later phase of his career), this is Burton’s bleakest, knottiest movie.

| 3.5 | The Nightmare Before Christmas | 1993 |

| 3 | Ed Wood | 1994 |

| 3.5 | Mars Attacks! | 1996 |

Even though Batman Returns was a box-office disappointment relative to its predecessor, it was still a sizable success. Having directed nothing but hits since becoming a feature-film director, Burton spent the mid-1990s cutting loose a little, experimenting with ideas that were more unstructured—and often uncommercial. In the process, Burton solidified his brand, though these were also the last few years where he only made “Tim Burton movies.” The post-1999 Burton filmography is more Batman than Batman Returns.

Technically, 1993’s stop-motion-animated The Nightmare Before Christmas isn’t even “a Tim Burton film,” since it was directed by fellow CalArts alum and former Disney grunt Henry Selick. But it’s definitely “a Tim Burton movie,” since he was the one who came up with the story, the characters, and the overall visual design—and he got his name above the title on the poster. First conceived when Burton was a Disney employee—and scotched because his bosses didn’t see any potential in the idea—The Nightmare Before Christmas is a Burton-esque riff on the old Rankin-Bass holiday specials, imagining what would happen if the ruler of “Halloween Town” kidnapped Santa Claus and tried to handle Christmas himself. Danny Elfman’s songs are an acquired taste, and there’s really only enough plot here for a half-hour TV show, but on the visual side alone, The Nightmare Before Christmas is the most unfettered blast of Burton’s subconscious since Beetlejuice. From characters like “the clown with the tearaway face” to the landscape dominated by slanted lines and spirals, The Nightmare Before Christmas is so imaginatively designed that it’s a shame it has to have a story at all—let alone one that ends yet again with with a good guy rescuing a blank girl from a bad guy in a dark tower. The Nightmare Before Christmas is also another crucial peek into Burton’s often-conflicted point of view. For someone so associated with outcasts and monsters, Burton is surprisingly pro-Santa in Nightmare. His affection for weirdos has its limits.

Burton’s mixed messages work against 1994’s Ed Wood, a biopic of a man often called the worst director who ever lived. Burton reunites with Johnny Depp, who plays Ed as a gung-ho impresario, so in love with the idea of making movies that he uses any resource available—stock footage, washed-up actors, cheap sets—to fill screen time. Ed Wood looks amazing, with Stefan Czapsky’s high-contrast black-and-white cinematography accentuating every stray piece of fuzz on Wood’s angora sweaters. The movie sounds good, too, with Burton giving Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski’s script (adapted from a Rudolph Grey book) the snappy rhythm of a 1930s screwball comedy. But Burton’s tendency to “cute up” the eccentric has him turning real people into insubstantial cartoons. The best parts in Ed Wood involve Ed hustling to put on a show (often while wearing women’s clothes) or Martin Landau’s foul-mouthed, embittered Bela Lugosi ranting about how show business turned him into a penniless junkie. The scene where Ed films Bela for the last time, and catches him literally taking a moment to stop and smell the flowers, is a wonderful reminder of how every movie is a personal statement to some extent—as well a reminder of Burton’s friendship with Vincent Price. Otherwise, though, Ed Wood is overly engaged with poking fun at the pretensions of Ed and his motley crew. It’s a loving mockery, but it’s still coming more from a place of superiority than empathy.

Ed Wood was one of Burton’s most critically acclaimed films, but it flopped at the box office. Burton bombed even more spectacularly with his next film, 1996’s Mars Attacks! Based on a lurid Topps trading-card series that was yanked from stores in the early 1960s due to parental complaints, Mars Attacks! is like Burton’s version of a star-studded, over-the-top 1970s disaster picture. Everyone from Jack Black to Jack Nicholson (in a dual role!), Jim Brown to Tom Jones, Glenn Close to Pam Grier, and Michael J. Fox to Rod Steiger plays an assortment of oddball Americans overrun by tiny, green-brained Martians. In the year of the straightforward alien-invasion epic Independence Day, audiences in the U.S. didn’t have much use for Burton’s aggressively silly, largely plotless slapstick comedy. (The film did much better overseas.) But like The Nightmare Before Christmas, Mars Attacks! is a boon for fans of the freewheeling Burton. The movie is just plain nuts, from the opening scene of burning cattle to the scene where a dog with the face of Sarah Jessica Parker makes out with Pierce Brosnan’s dripping decapitated head. There’s some method to the madness. Structured like the trading cards (moving from one overstuffed tableau to another), and designed to look like a Las Vegas replica of the Kennedy era, Mars Attacks! succeeds in making a familiar genre look foreign, right down to the nasty little villains and the “ack” noises they make when they talk. The movie is a mess, but it’s a fun mess—and one of the rare older movies that almost needs to be post-converted into 3-D.

| 3 | Sleepy Hollow | 1999 |

| 2.5 | Planet Of The Apes | 2001 |

| 4 | Big Fish | 2003 |

| 3.5 | Charlie And The Chocolate Factory | 2005 |

| 3 | Corpse Bride | 2005 |

| 3.5 | Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber Of Fleet Street | 2007 |

After Mars Attacks! underperformed at the box office, Burton had a long layoff, during which he produced a couple of films and developed projects that came to nothing—including a notorious Nicolas Cage Superman movie. He also released a 1997 collection of morbid, Edward Gorey-styled illustrated children’s poems, called The Melancholy Death Of Oyster Boy & Other Stories, which in 2000 he and Flinch Studio adapted into the crudely animated, depressingly shoddy web series The World Of Stainboy.

Burton returned to feature filmmaking with a movie more workmanlike and less personal than anything he’d made to that point. Sleepy Hollow stars Johnny Depp as Washington Irving’s cowardly, superstitious schoolteacher Ichabod Crane, refashioned for the movie as a squeamish cop with progressive ideas. Seven screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker frames the story as a mystery, with Depp’s Crane trying to figure out which of Sleepy Hollow’s flamboyant citizens summoned the vengeful ghost The Headless Horseman. Meanwhile, Burton and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki designed and shot the movie to resemble a Hammer horror picture, and Burton detours from the main action occasionally to stage little scenes of Crane enjoying both the technological wonders of the modern word and the effectiveness of old-fashioned illusions. The results are often highly entertaining. Though R-rated and bloody, Sleepy Hollow is more comic than horrific, and it’s at its best when Ichabod is trying to explain cutting-edge criminology while severed limbs are flying and spurting all around him. But Burton never really seems to connect to the script’s evocation of a panicky America approaching a new century, and the intentionally stiff performances and climactic tower battle feel like warmed-over versions of what Burton has done before. The conventionally heroic happy ending also comes off as a sop to mainstream audience—and one that worked, since Sleepy Hollow became Burton’s first huge hit since Batman Returns.

Burton hit big again with his 2001 update of the 1960s science-fiction classic Planet Of The Apes, starring Mark Wahlberg as an astronaut who travels through a time-storm and ends up on a future-world governed by talking chimpanzees, orangutans, and gorillas. The cast is game—especially Paul Giamatti as a flustered slaver—and Burton’s Planet Of The Apes is a lot of fun to look at, with Burton framing and staging the action like a particularly muscular 1970s comic book. But the committee-written script is a mishmash of ideas from the original movie series, grabbed seemingly at random and delivered as fourth-wall-breaking winks to old Apes fans. The movie is breezy to a fault, and lacks any of the spine-tingling creepiness or social commentary of the source material. (Even Helena Bonham Carter’s compassionate chimp character looks like a pretty soccer mom, as though someone at 20th Century Fox wanted to make sure that the good apes weren’t too off-putting.) In the end, the remake’s best nod to the first Planet Of The Apes is unintentional. In the 1968 film, Charlton Heston walks through the wreckage of his old Earth; in the 2001 version, Wahlberg is stranded amid the remnants of the old Apes movies.

Burton followed up his two least flavorful films (and, distressingly, two of his most popular) with a real departure, and his best movie in a decade. Adapting Daniel Wallace’s novel Big Fish with screenwriter John August, Burton made a film that put his usual freak show into a richer, more meaningful context. Albert Finney plays Ed Bloom, a dying storyteller who shares his fabulous autobiography one last time with his unappreciative son Will (Billy Crudup). Ewan McGregor plays the younger Ed, a happy wanderer who journeys from an edenic Alabama small town to a colorful circus to the Korean War—and back again—all while befriending amazing characters and pining for his true love, Sandra. As is often the case in Burton’s films, the women’s roles in Big Fish are more ornamental than fleshed-out, and the sometimes overbearingly syrupy quality may be a remnant of the project’s origins as a Steven Spielberg film. But while not all of Ed’s anecdotes are as magical as he believes, about every 10 minutes or so, Burton comes up with an image or a moment that’s genuinely breathtaking, especially in the secret Shangri-La of Spectre, Alabama, where Ed charms a woman played by Helena Bonham Carter. There’s a depth of feeling to Big Fish that’s lacking in the films that immediately precede it. Maybe it was because Burton was getting older, and identified with the script’s idea of looking at life’s rites of passage from different angles. Maybe he saw some of himself in Will: someone who wishes he had more of a reason to hate his happy family and idyllic childhood. Or maybe Burton couldn’t resist the opportunity to stage a scene as self-defining as the one where the young Ed dreams of daffodils while shoveling elephant shit. Ed’s story has a lot in common with Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, in that it’s a about a likable guy who touches other people’s lives. But Ed’s circus apprenticeship has a lot in common with Burton’s early years in the Disney combine, too.

With 2005’s Charlie And The Chocolate Factory, Burton was back into the remake business, but this time the Big Fish buzz carried over, and with August writing the script again (based on the book by one of Burton’s heroes, Roald Dahl), he made a film much more heartfelt than either Sleepy Hollow or Planet Of The Apes. Actually, Charlie And The Chocolate Factory may be a little too heartfelt. Burton and August betray Dahl’s spirit and break the movie’s strong spell in the last 20 minutes, via an unnecessarily corny new ending that sees kindly little boy Charlie (Freddie Highmore) helping eccentric millionaire chocolatier Willy Wonka (Johnny Depp) heal his relationship with his estranged father (Christopher Lee). Up until then, though, Burton’s version of this story is both darker and livelier than the 1971 movie, drawing thicker, gnarlier lines around the poverty of Charlie’s family, the selfishness of the children who win golden tickets to tour Wonka’s factory, and the wonders of the factory itself. At times over the years, Burton has indulged Johnny Depp’s whims too much in their collaborations, but Depp is exactly the right level of odd as Wonka. His high-voiced, fussy portrayal is part Michael Jackson, part Andy Warhol, and part Mr. Rogers. Here, Depp is a caricature of the temperamental genius—not unlike Burton—who gets annoyed when people question his art: “Candy doesn’t have to have a point… it’s candy.”

Just a few months after Charlie And The Chocolate Factory came out, Burton finished and released a stop-motion feature that had been in the works since Big Fish. Corpse Bride is based on a 19th-century folktale about a man who accidentally marries a dead woman, and has an adventure in the underworld before getting back to the woman he really loves. Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter provide the voices (and the facial models) for the groom and the cadaver, respectively, and maybe it’s because Burton had been working with one, the other, or both pretty much non-stop since Sleepy Hollow, but the work here from all three comes off as more than a little exhausted. As with The Nightmare Before Christmas, Danny Elfman provides songs that are overly busy-sounding (albeit catchy), and as with too many Burton films, the third act devolves into frenetic chases and violence, capped by a scene of a big meanie getting his comeuppance. But at least the meanie is voiced by the always-enjoyable Richard E. Grant, and at least Burton and his co-director Mike Johnson have some fun when they leave the land of the living. A scene of the hero reuniting with his dead friends and pets is such a quiet, lovely moment that it makes the rest of the film seem all the more clamorous. A half-hour version of Corpse Bride that only focused on those little grace notes would’ve been one of Burton’s best.

Similarly, Burton’s 2007 adaptation (with screenwriter John Logan) of the classic Stephen Sondheim/Hugh Wheeler musical Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber Of Fleet Street is so close to being great, it’s all the more irritating that it turned out merely good. Burton was a longtime Sweeney Todd fan, and even the not-always-easy-to-please Sondheim has admitted that Burton’s affinity for tasteful grotesquerie made him an ideal director for the movie version of his Broadway show about an obsessed serial killer. But once again, the decision to default to Depp and Carter as the leads—two actors who look right for their parts, but who lack the vocal range for one of Sondheim’s most operatic scores—is a handicap. There are other preventable errors too, including Burton cutting the song “The Ballad Of Sweeney Todd” entirely, which robs the movie of a couple of cathartic highs. All of that said, Sweeney Todd is still graced with plenty of Sondheim’s sophisticated, witty songs, which dissect the cruel social order of Victorian London. And Burton does them justice visually, with the help of towering Dante Ferretti sets and swooping Dariusz Wolski cinematography. Visually, Sweeney Todd is a tour de force, giving gothic horror the visceral kick that Sleepy Hollow lacked, while also zipping through the city to peek in on proper-looking people and their awful secrets.

| 2.5 | Alice In Wonderland | 2010 |

| 2 | Dark Shadows | 2012 |

| 2.5 | Frankenweenie | 2012 |

| 3.5 | Big Eyes | 2014 |

In 2006, Burton made his first music video, for The Killers’ song “Bones.” It was a good match of band and director, given that The Killers, like Burton, have become unlikely chart-toppers by mixing expressive older pop styles with their own skewed personalities. The “Bones” video is unmistakably Burtonesque, too: Two lovers watch a Ray Harryhausen movie at a drive-in, then head to the beach, where they strip off their clothes and skin, and roll around in the sand, doing a skeletal version of From Here To Eternity. The Killers/Burton collaboration worked so well that they repeated it in 2012 for the song “Here With Me,” in a video that stars Craig Roberts as an obsessive loner who goes on romantic excursions with a life-sized wax model of his favorite star (played by Winona Ryder). Burton effectively undercuts the song’s surging romantic vibe, turning it into a dark, sick story of objectification.

Yet as good as Burton’s two Killers videos are, they’re also indicative of where he wound up in the 21st century: as an artist with a style and a set of thematic preoccupations he could too easily repeat, whether in a big-budget Hollywood picture or a four-minute commercial for a rock band.

It may sound short-sighted to call a movie that made more than a billion dollars worldwide a failure, but Burton’s 2010 Alice In Wonderland is such a bombastic, dispiriting mess that its massive box office almost seems like a mark of shame, as though Walt Disney Pictures was rewarded for pandering. Burton and screenwriter Linda Woolverton—working with a top computer-animation team—recast Lewis Carroll’s children’s book as half coming-of-age story and half Lord Of The Rings-style fantasy epic, with Mia Wasikowska playing a marriage-bound 19-year-old who escapes to the surreal land she dreamed of as a girl. Burton’s Alice is another feast for the eyes, especially in 3-D, and it’s wonderfully bizarre at times—like a heavier version of Mars Attacks! or Beetlejuice. The key word there, though, is heavy. As Alice lands in the middle of a dispute between two queens (played by Helena Bonham Carter and Anne Hathaway), Alice In Wonderland becomes increasingly violent and repetitive, with references to Carroll that start to feel shoehorned-in (or, as with Planet Of The Apes, winking). The costumes are stunning, the sets are perfectly Burton—with plenty of curlicue trees—and Carter gives a fun performance as the capricious, misshapen Red Queen. But Danny Elfman’s score is overbearing, and Johnny Depp’s Mad Hatter feels like a mash-up of several other roles he’s played for Burton, never finding the right pitch or energy.

For further evidence that the Burton/Depp collaboration may be wrung dry, look to 2012’s Dark Shadows, a film Burton reportedly made as a favor to Depp, who’d been a fan of the horror-inflected TV soap opera since he was a boy. Depp plays Barnabas Collins, an ancient vampire who reawakens in 1970s Maine, and tries to restore his fallen family to its former position. The first 20 minutes or so of Dark Shadows are genuinely haunting, telling Barnabas’ story in the 1770s and giving the soap’s mythology the kind of visual grandeur it lacked on TV, where the characters tended to talk about the thrilling moments of their past rather than playing them out. Then the movie shifts to the 1970s, scored to the hazy, somber tones of The Moody Blues’ “Knights In White Satin.” But the nostalgic, melancholic atmosphere is quickly undercut by Seth Grahame-Smith’s jokey script, and by Depp’s deadpan comic performance, which together play up the irony of a grim vampire stuck in the smiley-face era. It’s good to see Michelle Pfeiffer again in a Tim Burton film (playing one of Barnabas’ descendants), and Dark Shadows is mildly interesting as another of Burton’s pastiches of different genres and different eras. But the movie quickly loses its connection to its source material—save for the long, talky scenes—and it lacks Burton’s usual imaginative spark.

The creative slump continued with the same year’s Frankenweenie, a feature-length 3-D stop-motion-animated update of Burton’s 1984 short. There’s nothing especially wrong with the new Frankenweenie. The story still works, and the movie looks fantastic, with lots of fine detail, all the way down to the dead grass on the Frankensteins’ lawn. But the choice to use a reduced voicecast—with actors playing multiple roles for no real reason—makes this Frankenweenie feel slight, as does the way Burton and screenwriter John August pad out the third act with generic Burton mayhem. Also bothersome: the addition of a subplot about a science teacher who gets drummed out of his job by the town’s science-averse parents. As delightful as it is to hear the voice of Martin Landau, playing a character modeled after Vincent Price, the sentimentality of the storyline clashes with the cockeyed tone of the rest of the film. It’s the Charlie And The Chocolate Factory problem all over again, except that instead of “improving” Dahl, it’s as though Burton’s delivering life lessons to his younger self.

After three dreary films, Big Eyes is refreshingly zestful. And depending on what Burton does next, the movie could be called a comeback—or perhaps even the starting point for a new phase in his career. Re-teaming with his Ed Wood screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, Burton tells the story of Margaret Keane, who spent years cranking out cutesy paintings of sad children that her husband Walter claimed as his own. Christoph Waltz’s performance as Walter is so artificial and manic that it throws Big Eyes off-kilter at times, especially toward the end of the film, when the Keanes fight each other in court. But the movie has the kind of assuredness that veteran directors often bring to their later works. It says what it wants to say, then rolls credits, without a lot of fuss. What Big Eyes says is that popularity is unpredictable, and that the lines between art and manufacturing are sometimes thin, but that a patient, sincere person can still find a way to make even mass-produced products personal.

Or at least that’s the message of Margaret’s scenes. Here and there in Big Eyes, Burton also shows some sympathy for Walter: a man with a knack for selling art by giving it a public persona and a backstory. Throughout his career, Burton has been both Margaret and Walter, and as he’s matured, he’s drawn fewer and fewer lines between his heroes and villains, his conservatives and free-thinkers. One of the reasons Burton has been so successful is that he’s understood something about human nature that resonates broadly: Everyone, at some time or another, feels like a freak.