With the NBA Finals starting, capping a year when sports analytics have started to transform hoops just as surely as the Moneyball crowd changed baseball, we felt the time was right to apply the same rigorous mathematics to basketball movies that stats geeks apply to long twos and the value of hacking poor free-throw shooters. The statistical breakdown below takes a scientific approach to the cinematic hardwood, whether filmmakers are shooting for the inspirational, the magical, the astrological, or for a more realistic look at the game, and the odds-bucking men, women, or men-posing-as-women who play it. And while we can’t claim to be comprehensive—apologies due to Gabe Kaplan and a phenomenally gifted golden retriever—we feel like the sample size is large enough to where academics and data journalists can extrapolate all sorts of publishable conclusions.

A note on the categories: Skill denotes the degree to which the actors onscreen could pass for real basketball players. Sap expresses the amount of heart-tugging sentimentality in the movie. Shooting Percentage is how many made baskets are shown, vs. missed baskets, which would secure most movie characters a spot on any NBA team. Magic is the degree to which the supernatural plays a role, and Court Time considers how much basketball is in the movie and how much time is taken up by other, surely more boring concerns. Now pump up your Reeboks and let’s get started:

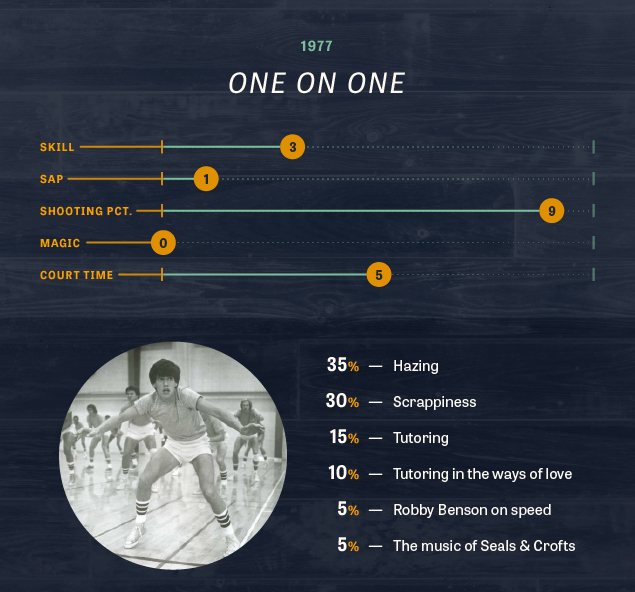

An undersized point guard—a twiggy 5’10”, with a John Stockton haircut—Henry Steele (Robby Benson) is a big deal in the small town of Turnip Truck, Colorado, but when he’s recruited to play at Western, an NCAA powerhouse in Los Angeles, his dopey naïveté makes him a target for abuse. A sexy hitchhiker extorts all but his last dollar from him, his coach (G.D. Spradlin) is a hard-driving sadist in the classic Bobby Knight tradition, his teammates could all floss their teeth with him, and his tutor (Annette O’Toole) assumes he’s just another dumb jock. One On One treats his freshman year as a two-pronged coming-of-age story, as Henry learns how to toughen up as a player and how to win the heart of a much more sophisticated and experienced upperclassman.

Though none of the basketball action is remotely convincing—Benson does strange, springy hops of excitement whenever he scores—and the love story is just a notch above perfunctory, One On One goes surprisingly deep into college sporting issues that are still talked about today. Henry needs shady odd jobs and alumni scams to keep money in his pocket. The demands of his basketball schedule overwhelm him and leave little time for academics. And his scholarship is threatened by the whims of a coach who pressures him to renounce it. Spradlin embodies the type of college-level disciplinarian who believes he’s shaping players’ characters by bullying them, which makes it satisfying when Henry finally gets off the bench and performs heroically on national TV. Nearly 40 years later, plenty of college players are no doubt nursing the same fantasy.

There’s a deep, deep 1970s-ness to The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh, a misbegotten basketballsploitation movie from one of the NBA’s least popular eras. Julius “Dr. J” Erving stars as Moses Guthrie, a hotshot who has trouble playing in synch with his Pittsburgh Pythons teammates until the ballboy and an astrologer named Mona Mondieu (Stockard Channing) convince the Pythons’ childlike, impressionable owner (Jonathan Winters) to fill the entire roster with players born under the Pisces sign. Overnight, this ragtag band—consisting of a preacher (Meadowlark Lemon), a rapping DJ, teenage twins, a mute, a Native American, a Black Muslim named “Truth,” and a squat white guy called “Setshot”—gels as a unit. Soon, the renamed Pittsburgh Pisces become disco-styled sensations, playing on a rainbow-colored floor in glittery satin uniforms.

Besides Erving, The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh features a healthy share of roundball heroes in bit parts, including Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bob Lanier, Cornbread Maxwell, Jerry Tarkanian, and announcers Marv Albert and Chick Hearn (supplemented by Harry Shearer as local newsman “Murray Sports”). But there’s barely any movie here at all—just lots of shots of Erving dunking in slow motion, between one-note jokes based on the characters’ ethnicities. This was clearly meant to be a star vehicle for the Doctor, who gets the big rousing speech during the final game (“The astrology thing is just a mirror,” he unconvincingly mumbles), and gets to seduce the ballboy’s sexy sister with lines like, “You know I believe in twos…”

Teen Wolf is a basketball movie. The movie opens during a basketball game, and Scott Howard, the Teen Wolf, makes his pivotal transformation during a basketball game. Also: what the hell is Teen Wolf if it isn’t a basketball movie? It certainly doesn’t have anything to do with any other recognizable aspect of real life.

In the grand tradition of 1980s movies in which no one’s actions seem to have any consequences, Teen Wolf tells the story of a teenager who turns into a werewolf. Instead of being like, “Whoa, hey, that’s weird as hell, that teen’s a wolf,” everyone loves the Teen Wolf: Girls want to kiss the Teen Wolf, boys want to be the Teen Wolf, school administrators see the Teen Wolf as a threat to their authority. Nobody does a single thing that makes any sense during the 90 minutes of Teen Wolf, which, in a way, is pretty remarkable: The dedication to incoherence is what ultimately makes the movie cohere, so far as it does. This peaks when Scott comes home at one point to find his dad playing one-on-one against his love interest. They both have their shirts tucked in, and the tone is bizarrely sexual. This scene is upsetting.

So, the real question: How’s the basketball in Teen Wolf? People who’ve never, ever seen basketball played in real life would still watch these basketball scenes and think, “That can’t possibly be basketball.” Why does no one ever pass? Why do the opposing players let the Teen Wolf dribble around unopposed? What makes the Teen Wolf good? Are they just afraid of his furry body? These are all mysteries of the Teen Wolf. We can’t hope to understand them.

Just as Bull Durham and Field Of Dreams form a kind of dichotomy of baseball movies—the former for the thinking fans, the latter for the hokum-hounds—so White Man Can’t Jump and Hoosiers fill much the same roles for basketball. But Hoosiers is much, much better than Field Of Dreams. Based loosely on the true story of a small-town Indiana high-school team that won the state championship in the early 1950s, the film stars Gene Hackman as an outsider who wins over the residents and teens of Hickory, Indiana with his passion for the game and his insistence on conservative, team-centered play. As he inspires his players, he helps bring a sense of pride and dignity to Hickory, and to underestimated folks everywhere.

Hoosiers pretty much travels a straight line from “this team stinks” to “no, this team is amazing,” and though director David Anspaugh (who later made the even better Rudy) and cinematographer Fred Murphy give the film a burnished, old-fashioned look, Jerry Goldsmith’s synth-heavy score sounds extremely 1980s. But those are just nitpicks. There’s a reason why nearly every sports drama post-1986 borrows Hoosiers’ look, mood, and emotional beats: The damn thing just works. From Dennis Hopper’s Oscar-nominated performance as the town drunk to the slow-clap the team gives the coach before a big game, this movie is as reliably square as the box-and-one.

In White Men Can’t Jump, the white man, Billy Hoyle (Woody Harrelson), can’t jump, but he can ball, even if he looks more like he should be carrying the Beastie Boys’ subwoofers than going anywhere near a court. That’s by design: He’s a hustler, and after he works Sidney Deane (Wesley Snipes) on the courts in Venice Beach, California, the two men enter a sort-of collaboration that also ends up becoming an Enlightening Cross-Cultural Friendship. Written and directed by Ron Shelton, White Men Can’t Jump has all the elements of a manipulative Lifetime Original movie, but Shelton’s deft script is smart and funny enough to avoid most of the expected pitfalls. More importantly, the pairing of Harrelson and Snipes is a gift from God. Seriously: Every movie should star Woody Harrelson and Wesley Snipes.

For what’s billed as a basketball film, White Men Can’t Jump is remarkably baggy and weird: There’s a mob subplot, plenty of time given to Hoyle’s relationship with his girlfriend Gloria Clemente—if charisma were a currency, Rosie Perez would be the world’s richest person—and a fixation on the show Jeopardy! And the basketball itself only resembles real basketball in the way onscreen sex resembles real sex. But all of these dressings, which bloat the movie to nearly two hours and have about the success percentage of a mid-range jumper, are secondary to the chemistry between its stars. Harrelson and Snipes have an easy, athletic rapport that makes the jokes they fire back and forth endlessly a sort of ongoing jam on the movie’s central concept. Shelton has Hoyle lay it out for Deane and the viewer: Everyone knows white dudes want to win, and black dudes want to look good. The true success of the movie is in showing that this kind of easy stereotype couldn’t be further from reality.

As a college basketball star, Jimmy Dolan (Kevin Bacon) could always rely on his patented “shake and bake” move, a combination of fancy footwork and trickery that left his opponents unsure which way he was going. As an assistant coach charged with recruiting future stars, however, his footing isn’t as certain. After blowing his school’s shot at an obnoxious hot prospect, he hits upon a drunken idea after seeing the towering Saleh (Charles Gitonga Maina) in the background of a video touting the school’s missionary outreach in Africa. Traveling to Kenya, Jimmy lives among the fictional Winabi tribe as he attempts to convince Saleh to return with him to America to play basketball.

But first Jimmy has some, sigh, lessons of his own to learn, which he does by, sigh, learning to care more about Saleh and his people than his own career by slowing down to their simpler, slower way of life. “You give me a sump pump and a three-inch pipe, and I’ll cut your workload in half,” Jimmy tells Saleh as they draw water from the river. “But then we couldn’t visit each other,” Saleh replies. First, though, it all comes down to one big game—via a lot of constructive editing that cuts to long shots as soon as the actors go for a basket—between the Winabi people and a team recruited by an evil copper baron (Mabutho “Kid” Sithole) who’s never heard of fair play. Does good triumph over evil? Does Jimmy get his soul back and get Saleh to commit? Do the credits roll after the film freezes in the middle of a high five? There are no sure things in basketball, but inspirational, Disney-produced sports movies are another story.

Blue Chips is about Nick Nolte screaming. Or it’s about Nick Nolte, playing a college coach named Petey Bell, being put into situations in which he might have to scream. Or: It’s about Nick Nolte, playing a college coach named Pete Bell, trying to resuscitate his once-mighty program with the eponymous blue chips—prospects whose skill and value is so great that they could take him to the promised land in their freshman year, but also mean that Bell might have to compromise his commitment to a clean program. You see, Pete is one of those old-fashioned coaches, the kind who expects players to go to class and not ask for duffel bags filled with $30,000. And what’s a guy like that to do when Rick Pitino is out there making his big-hearted young men look like mop-boys?

There are two things worth knowing about Blue Chips. The first is that it’s directed by William Friedkin, who shoots the basketball scenes like he shot the pursuits of The French Connection—there is velocity and nothing else, a constant, unstoppable movement forward. What could’ve been a rote by-the-numbers basketball movie in less-agile hands becomes a tactile exploration of the game as it’s played; it would be hard to find a fictional film that does better with the actual sport than this one does. Part of that has to do with the second thing, which is that the actors, all high-level athletes, played real games for Blue Chips. The beauty and frenetic motion of basketball shines through, and good thing, too, because by the end of Blue Chips, the off-the-court story has derailed into a deep dark canyon of melodrama. Blue Chips is the kind of narrative in which the hero crosses so far into moral rectitude that he ends up corrupted by his own virtue; when the ostensibly villainous booster, Happy (J.T. Walsh) argues about why the kids should be paid, it’s hard not to think, “Dude’s got a point!” Blue Chips does not think he’s got a point. But even if the film sells itself out by the end, the basketball and Nolte’s performance—not to mention a superb job by Shaq in his first acting role—make this one of the more successful, and realistic, sports movies out there.

The New York Knicks are having a hard time of it as the 1996 comedy Eddie opens, and no one has stronger ideas about how to fix the team’s downward slide than Eddie Franklin (Whoopi Goldberg), a limo driver and dispatcher who uses her radio to entertain her fellow drivers with play-by-play of each bungled game. When the Knicks get sold to “Wild Bill” Burgess (Frank Langella), a wealthy Texan who values showmanship almost as much he values money, Eddie gets a shot at proving she actually knows what she’s talking about. After driving Burgess to Madison Square Garden, Eddie “wins” a rigged contest that makes her the team’s honorary coach for the second half of a game. But when Burgess clashes with the team’s hard-driving head coach, John Bailey (Dennis Farina), Wild Bill decides to make the position permanent.

A lot of theoretically comical interactions between Eddie and moonlighting NBA players whose basketball chops outclass their comic timing follow as the film heads down a predictable path. At first, Eddie doesn’t do all that well. Then, once she realizes the team needs someone who cares about them and their personal lives as much as she cares about winning the game, the Knicks start to turn it around via a series of montage sequences. Their progress marked by cameos and commentary from Rudolph Giuliani, Dennis Rodman, David Letterman, and others. Though six credited screenwriters worked on the film, Knicks great Walt Frazier gets the film’s biggest laugh when he exclaims, “Hey! Yo! That’s my jersey!” after his retired jersey gets set on fire.

Michael Jordan racked up his first NBA championship win in 1991 with the Bulls, but well before that, he was already an international superstar—a multiple record-holder, All-Star MVP, Sports Illustrated cover subject, and fan favorite with his own line of Nike shoes, the Air Jordan. He was all over TV commercials in the 1990s, playing a genial, game version of himself who was always ready to beam approvingly upon anyone enjoying McDonalds, wearing Hanes, eating their Wheaties, and so forth. But 1992 was a particular turning point, when the “Hare Jordan”—the seventh iteration of Jordan’s namesake Nike shoe—made it to the market, complete with a wisecracking Bugs Bunny as a bonus pitchman. The first Hare Jordan ad, which featured cackling bully basketballers, cartoon mayhem, familiar Bugs catchphrases, and Jordan in genial-competitor mode, now looks like a quickie dry run for 1996’s Space Jam, which does all the same things, at much greater and brighter length.

The film—still the most lucrative basketball film in history, not even counting any product-placement money for the film’s acknowledgement of Gatorade, McDonald’s, Wheaties, etc.—has the Looney Tunes gang facing kidnapping by the employees of a dodgy animated intergalactic theme park that needs a new set of star attractions. Noticing their captors are all tiny, the Tunes put their freedom on the line in a basketball game, but the theme-parkers steal the basketball skills (and height) of five NBA stars, so Bugs, Daffy, and company enlist Jordan’s help to coach their team to victory. The film doesn’t actually spend as much time on the court as the premise suggests—the big game only lasts about 15 minutes, with as much screen time spent on downtime and character business as on shooting and scoring. But the film does cover a gamut of play, from an energetic montage of real NBA dunks to a flashback to Jordan’s childhood post-midnight practice sessions to a neighborhood game, witnessed by a morose Charles Barkley after the aliens hijack his talents. When the Tunes and their adversaries are getting their game on, it’s an abstract, unrefereed cartoon free-for-all, where Yosemite Sam and Elmer Fudd shooting out an opponent’s teeth, or Daffy painting a player’s ass red so a cartoon bull will charge him, counts as legal defense. At 67-66, the climactic game is a surprisingly low-scoring one, but really, the film was about setting up for more than a billion dollars in merchandising sales, not about the rules of the game.

Jake Shuttlesworth (Denzel Washington) is serving a hefty stint in prison for… what? It’s hard to tell, and that’s just one of the many subplots Spike Lee juggles as he tells the story of Jake’s son, Jesus—played with remarkable capability, though not much emoting, by real-life basketball star Ray Allen—in the week leading up to Jesus’ decision about where to attend college. Jesus is the No. 1 basketball prospect in the country. Unlike most college-bound seniors, his enrollment won’t just decide where he’ll be drinking Keystone Light for the next four years; many people, maybe even every person he knows, have their own reasons to push him one way or the other.

Especially Jake, whom Washington plays as a desperate man held aloft by the buoyancy of his charm. Jake is on “work-release” from prison so he can convince Jesus to attend Big State, the governor’s alma mater. Schools like “Big State” and “Tech U” are only one of the many elements that give He Got Game a sort of fairy-tale sensibility; Lee’s stylistic fireworks display also includes docu-style direct-camera address, rapid-fire cutaways, and dressed-up monologues by characters with names like Big Time and Coach Billy Sunday (played by John Turturro as if his Miller’s Crossing character escaped into the late ‘90s). But even if He Got Game can drag around the same millstones that tend to trouble Lee—the Milla-Jovovich-as-prostitute-with-a-heart-of-gold story is so unnecessary, it feels like a joke—He Got Game might be the most ambitious basketball movie ever made. It considers the dark side of athletic stardom with empathy and pathos. There’s a reason Lee named this guy Jesus: the temptations are great, and the fall omnipresent. Viewers who think basketball players are spoiled, conceited narcissists get the personal treatment from He Got Game, which wants to say, “You would be too. Or you’d be worse.”

The title of Gina Prince-Bythewood’s debut feature, Love & Basketball, presents its two central nouns as equally important, and the film follows suit. The 2000 romantic drama positions its central couple, Quincy (Omar Epps) and Monica (Sanaa Lathan), as rivals and near-equals both on and off the court, and their stop-start romance is inextricably linked to their successes and failures as aspiring professional athletes. Neighbors and frenemies since childhood, Monica and Quincy love the sport more than anything, and their bond is forged and tested on the court, as Quincy’s natural talent and confidence clashes with Monica’s scrappy determination in the face of a family and culture that repeatedly tells her, “Girls can’t play no ball.”

By tracing the ups and downs of two otherwise-comparable talents whose career trajectories are defined by their genders, Prince-Bythewood’s script gets at some tough truths about the prestige gap between men’s and women’s athletics. But by tying those observations to a winning romance charged by the sparking chemistry between Epps and Lathan, the film sidesteps didacticism, smuggling its still-trenchant message within a memorable movie romance. Prince-Bythewood is a former college athlete herself—she ran track at UCLA, in addition to being a professed lifelong ball player—and she brings a sense of care and expertise to the film’s portrayal of the sport. But her film truly shines in the moments that set competition aside and revel in the love of the game, and those who love the game.

There’s a point about a third of the way through Juwanna Mann where Kevin Pollak, playing the beleaguered, besmirched agent of the titular character, screams, “Somebody kill me!!!” It’s the only point in the entire movie that resonates; anyone viewing this film must be doing so against their own will while begging for the sweet mercy of death. Ostensibly a comedic farce, but offensive in both its actual content and in its profound lack of humor, Juwanna Mann follows Miguel A. Nunez, Jr. as Jamal Jefferies, a talented NBA player whose court antics—namely, stripping naked and shaking his genitals at a crowd full of innocent children—get him suspended from the league. Desperate to maintain his luxe lifestyle, Jamal enlists Pollak to help turn him into a busty, bawdy WNBA player named Juwanna Mann, because it’s a pun, do you get it? Also in on the ruse: Jamal’s aunt (Jenifer Lewis), who inexplicably agrees to help, even though he treats her like total shit throughout the film.

Even people who haven’t seen Juwanna Mann (don’t… just don’t) know how this thing goes down. Jamal clashes with the team’s captain, Michelle (Vivica A. Fox), then falls madly in love with her. Along the way, he learns important lessons about teamwork, humility, and most importantly, himself. Terribly derivative, terribly written, terribly acted, and terribly dull, Juwanna Mann takes several things for granted: 1) That the audience gives a shit about what happens to Jamal, the most patently unlikeable character this side of Frank Booth; 2) that female body parts and gay and transgender panic are innately hilarious—so hilarious, in fact, that they can carry an entire comedy; 3) that ultimately, women need a man to tell them they’re great before they can believe it themselves; and 4) that lazily telegraphing sensitivity about gender and sexuality is the same as actually conveying it.

Like Mike could be accurately described as a cynical exercise in brand extension, baiting children with the fantasy of slam dunks and room service in order to reinforce their devotion to the NBA, Nike shoes, and assorted other products on display. But give the film credit for this: It’s weird. Really weird. And it has a deep bench of supporting players, including Crispin Glover, Robert Forster, Eugene Levy, Anne Meara, and a young Jesse Plemons, trying out the pitiless stare he deployed later to unnerving effect in Breaking Bad. Glover, in particular, recalls Christopher Walken in The Country Bears with his unhinged performance as a conniving orphanage manager who at one point gets a post-Jerry Maguire Jonathan Lipnicki to talk by holding a lighter to the only picture of his mother. Like Mike goes through the requisite paces, but it’s much funkier than it needs to be.

It also helps that Lil’ Bow Wow brings genuine enthusiasm to the stock role of an orphaned moppet who wants nothing more than to be part of a family, and has magic intervene on his behalf. Getting the kid to the court requires a tortured sequence of events: a donated pair of shoes that once belonged to Michael Jordan, a lightning storm, gift tickets from an NBA head coach (Robert Forster), a halftime one-on-one promo involving the star player (Morris Chestnut), and an owner (Eugene Levy) willing to try a desperate gimmick to boost ticket sales. Also torturous is the odd-couple dynamic between the kid and the pampered star, which turns sappy once the star becomes the father he never had. But there’s fun in Like Mike’s basketball fantasy, especially when Bow Wow goes head-to-head with real NBA stars—posterizing David Robinson, breaking Allen Iverson’s ankles on a crossover dribble, and signing an autograph for Dirk Nowitzki. (“It’s for my sister.” “What’s her name?” “Um… Dirk.”)

Nearly every underdog sports story begins with an unorthodox coach teaching a band of misfits and/or showboats how to play with discipline. But fundamentals fetishists have rarely been as well-catered-to as they are with Coach Carter, a movie that’s almost all push-ups, suicide sprints, and lessons about hustle, teamwork, and commitment. Samuel L. Jackson plays the real-life Ken Carter, who took over a talented but sloppy Bay Area high school team in the late 1990s, then caused a stir when he started benching players for poor academic performance and “lack of respect.” The majority of Coach Carter consists of a stern Jackson squelching any flare-up of personality or exuberance in his players, in the name of making a larger point about how to be a man.

Director Thomas Carter (no relation) was a star on the high-school basketball TV series The White Shadow, and later helmed the Ben Carson biopic Gifted Hands and the syrupy football drama When The Game Stands Tall. Coach Carter is like a fusion of all those projects, mixing moralism and teen melodrama, with a special emphasis on how hard it is for these kids to stay focused on their GPA when they come from neighborhoods run by drug dealers. Coach Carter is well-acted (including a turn by a neophyte Channing Tatum as one of the players), but it’s less a movie for basketball fans than for those who derisively snort and then rhapsodize about the good ol’ days whenever they hear the phrase “student-athlete.”

Given Hoosiers’ perennial popularity, it’s surprising it took as long as it did for someone to make a movie out of one of the most uplifting, best-known basketball stories of all time. In 1966, El Paso’s tiny Texas Western College beat the powerhouse Kentucky Wildcats for the NCAA Championship, and made history by using only African-American players against Coach Adolph Rupp’s all-white squad. In 2006, Jerry Bruckheimer produced Glory Road, with a heavily made-up Jon Voight in a glorified cameo role as Rupp (approximating the coach’s John Huston-like rasp) and Josh Lucas as Coach Don Haskins, who defied the game’s “unwritten rules” and his own boosters by recruiting in urban areas around the country.

Glory Road leans heavy on the clichés of sports and racial-justice melodramas, with the requisite culture-clashes, the coach emphasizing a more controlled style of play, and overexplanatory radio-broadcaster voiceovers. There’s also an unpleasant streak of broad humor, as the school’s new stars adjust to the local cuisine (“Taco? Nacho? Burrito? I’m looking for hot dog-o.”) and get hectored by their parents into taking their studies more seriously. But somewhat atypically, the movie argues that Haskins’ rigor only worked once he allowed his men to bring a little razzle-dazzle to the court. And as corny as it may be, it’s hard to deny how stirring it is to watch a group of kids band together to strike a blow against bigotry—especially when they get to throw down a few unashamed dunks in the process.

Arriving at the end of Will Ferrell’s sports-riffing cycle, after Talladega Nights and Blades Of Glory, Semi-Pro seems like a half-assed excuse for some comedians to don afros and butterfly collars and make jokes about the disco-’70s cool of the American Basketball Association. That description is entirely true except for the word “half-assed”: Ferrell and a roster of comedy professionals (Andy Daly and Will Arnett as broadcasters of contrasting temperaments, Matt Walsh as a priest/referee, David Koechner as the ABA honcho, Andy Richter as a put-upon GM, and many others) use the latitude of an R rating to score laughs off both the period’s excesses and the humiliations of playing for a two-bit operation. Some of the gags reference ABA culture and not-quite-professional sports teams like the Flint Tropics. Other gags are just gags, like a poker night that inadvertently turns into a game of Russian roulette.

Ferrell stars as Jackie Moon, a one-hit-wonder (the song: “Love Me Sexy”) who’s invested his money and fame into being the owner/coach/starting power forward for the Tropics, but with the ABA folding into the NBA, low attendance and a bad team make it near-impossible for his team to survive the transition. That leads to the standard sports-movie business of recruiting a ringer (Woody Harrelson), whipping a bunch of slobs into shape, and making a run up the standings, but Semi-Pro screws around as much as it can. Particularly funny are Jackie’s outrageous attempts at promotional events, from a “free corn-dog night” if the team scores 125 points (they have no corn dogs) to Jackie wrestling a bear at half-court. (A shirtless Jackie Earle Haley wanders around the whole movie with a giant $10,000 novelty check that no bank will cash.) Semi-Pro isn’t as disciplined or rich a comedy as Bull Durham, but it has the same affection for silly, off-brand underdog teams and the locals who love them.

Along with the shoe contract, the endorsements, the videogame avatars, and other ancillary income, the NBA’s biggest superstars usually get a shot at big-screen glory: Think Ray Allen in He Got Game, Michael Jordan in Space Jam, Shaq in Kazaam, and Lebron James in the upcoming Trainwreck. Some are merely subpar in this capacity, while others max out on the Groot scale. Kevin Durant is among the most lovable, charismatic players in the NBA today—his MVP speech is Essential Weeping—but even Durant recognizes the Gheorghe Muresan-esque quality of his performance in Thunderstruck, a Freaky Friday knock-off he shuffles through with all the élan of a mid-season press conference. The blame for the film’s failure needn’t be put entirely (or even partially) on his head—his role is largely ceremonial, and he’s never seen outside a gym—but Durant’s bored indifference is its defining trait.

Despite the body-switching premise, Thunderstruck is basically Like Mike revisited: Runty but devoted kid basketball fan goes to NBA game, gets his ticket called for a halftime promo contest, something magical happens, kid becomes NBA-caliber player, kid goes back to being crappy in The Big Game, kid’s team wins The Big Game anyway. But the kid here, a 16-year-old geek played by Taylor Gray, doesn’t have anything like Lil’ Bow Wow’s charisma, and Jim Belushi, as his belligerent high-school coach, isn’t a character actor on par with Like Mike’s Crispin Glover/Robert Forster/Eugene Levy trifecta. It’s almost as if Thunderstruck exists to support the argument made by some pop-culture list a decade from now that Like Mike was an early-2000s cinema classic and a touchstone for a generation of NBA stars. In 2032, no one will be making that argument for Thunderstruck.

Our Movie Of The Week discussion of White Men Can’t Jump ends here. Don’t miss Scott’s Keynote on how Ron Shelton’s movie complicates the ideas of winning and losing, and Noel and Tim’s Forum discussion of the film’s very ’90s racial politics and idealism. And make sure to join us next week when we celebrate the biting satire and memorable music of Robert Altman’s Nashville.