Part 14: Beyond the Dune Sea

In early 1973, filmmaker George Lucas started a list of names. At the top: “Emperor Ford Xerxes II.” The list included “Xenos,” “Leilam,” “Owen,” “Mace,” “Biggs,” “Han Solo,” “Lord Anakin Starkiller,” and “Luke Skywalker.” This list, the first pen-to-paper result of a space-opera idea Lucas had been kicking around with others for years, led to a two-page document Lucas called “Journal Of The Whills, [Part] I.” On June 3, 2013, graphic novelist Alex Robinson and digital media manager Pete Bonavita, also known as Pete The Retailer, launched a podcast called “The Star Wars Minute.” Each of the first 122 episodes analyzed a single minute of the movie that resulted from those 40-year-old documents. Each of those episodes devote upward of 20 minutes of commentary to 60 seconds of screen time.

“The Star Wars Minute” is merely one among many offshoots of Star Wars’ popularity. But it’s as good example as any of how a few ideas in the head of a young USC grad have become a phenomenon much bigger than his 1977 science-fiction film Star Wars. (Another example: the need for its convoluted new title, “Star Wars—Episode IV: A New Hope.”)

Why? Of all the science-fiction films released in the long wake of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet Of The Apes, why did Star Wars take hold in a way no film before it had? None of the many answers are entirely satisfying. But combining a few of them lets us make some sense of the question.

Let’s go back. Back before the excitement of the forthcoming sequels, before Jar Jar, before old-time fans needed to clarify that Han shot first, before the action figures, before the disco records, even before the addition of “A New Hope.” Let’s go back almost to the start, to the summer before Star Wars. In July 1976, Charles Lippincott, then head of marketing for Lucasfilm, went to the San Diego Comic Con with a slide show. Before a crowd that Lippincott’s co-worker Craig Miller estimated as “a few hundred, maybe,” Lippincott revealed the first images from Star Wars. There aren’t many photos from the event, but those that remain look strange and a little poignant, particularly Lippincott manning a lightly trafficked Star Wars booth next to a Super 8 display, and a handful of curious people seeing Darth Vader for the first time as they sit politely amid many empty seats. Nobody in those photos knows what’s about to hit them.

Even Lippincott couldn’t have known: His Comic Con visit coincided with the last days of principal photography on what had turned out to be a difficult production, with Lucas frequently clashing with his British crew. The film entered a movie marketplace that had grown unfriendly to science fiction: 1976’s most significant science-fiction hit was Logan’s Run, and genre fans had moved their attention back to the small screen. Cover-dated August, 1976, the first issue of Starlog features an episode guide to Star Trek, and articles on The Bionic Woman and Space: 1999, but only a passing reference to The Man Who Fell To Earth. Its film features cover the King Kong remake and the giant-worm film Squirm, each in their own way a sign of science fiction reverting back to giant monster movies after a more experimental period. Subsequent issues of Starlog kept the focus there, cycling through Space: 1999, The Six Million Dollar Man, and Bionic Woman stories while virtually ignoring the movies. That started to change with the magazine’s sixth issue, which featured a banner with these words: “Coming: Star Wars.” It also featured a single page with two gorgeous, misleading pieces of production art from Ralph McQuarrie, and a short, not particularly accurate preview of the film that referred to “an ancient, mysterious technique for working one’s will, known simply as ‘the power.’” Oh, and it mistook Imperial stormtroopers for “robot guards.” One of those robot guards is wielding “a light sword or laser-sabre.”

Star Wars would either fill a need that hadn’t been met in a while, or foolishly bring a big science-fiction film to a moviegoing public that didn’t want one. Sitting at that table in San Diego, Lippincott had no way of knowing. Neither, really, did Lucas or anyone else involved with the film. But they suspected timing was on their side. Lucas and Gary Kurtz—his producing partner through Star Wars’ first sequel, The Empire Strikes Back, after which they split after disagreeing about the direction of what became Return Of The Jedi—set out to make a film in the mold of the old movie serials they’d grown up watching on television. They even attempted to license Flash Gordon, but decided to pursue an original project when that proved too financially and creatively prohibitive. Their idea wasn’t to continue the string of thoughtful, ideas-driven science-fiction films of the early 1970s, but to defy it with a fast-paced, effects-filled adventure of the sort that hadn’t been seen on big screens in years. It offered juvenile escapism and a simplistic conflict between good and evil, after a long period of downbeat films informed by the upheaval of the 1960s and ’70s.

Except that’s only true up to a point: For as much as Star Wars is a throwback, it’s also a film of its time, in ways beyond the shaggy haircuts sported by stars Mark Hamill and Harrison Ford. It’s worth remembering that Lucas and Kurtz, in parallel with Star Wars, worked on and off on Apocalypse Now, which they imagined as a Dr. Strangelove-like dark comedy set during the Vietnam War. Lucas’ interest in grappling with that war, which gave American Graffiti its half-tragic coda, extended into Star Wars. In a 1970s interview with Lippincott referenced in J.W. Rinzler’s invaluable book The Making Of Star Wars, Lucas says:

A lot of my interest in Apocalypse Now was carried over into Star Wars […] I figured that I couldn’t make that film because it was about the Vietnam War, so I would essentially deal with some of the same interesting concepts that I was going to use and convert them into space fantasy, so you’d have essentially a large technological empire going after a small group of freedom fighters or human beings.

In a note on an early draft of the film involving a planet of called Aquilae, Lucas writes:

Aquilae is a small independent country like North Vietnam threatened by a neighbor or provincial rebellion, instigated by gangsters aided by empire. Fight to get rightful planet back. Half of system has been lost to gangsters… The empire is like America ten years from now, after gangsters assassinated the Emperor and were elevated to power in a rigged election… We are at a turning point: fascism or revolution.

And in discussing Star Wars with writer Alan Dean Foster, who wound up penning the novelization of Star Wars published ahead of the movie, Lucas found another real-world parallel between Star Wars’s Rebel forces:

It happens in all countries when a certain force, which everybody thinks is wrong, begins to take over and nobody decides to stand up against it, or the people who stand up against it can’t rally enough support. What usually happens is a small minority stands up against it, and the major portion are a lot of indifferent people who aren’t doing anything one way or the other. And by not accepting the responsibility, those people eventually have to confront the issue in a more painful way, which is essentially what happened in the United States with the Vietnam War.

From a certain point of view, to borrow a phrase from a different movie, Star Wars isn’t an attempt to escape from Vietnam, but an attempt to recontextualize it, with the United States slotted into the role of the Empire, and the Rebellion standing in for the NVA and the Viet Cong. By the time the film reached screens, this source of inspiration was so deep in the mix—buried beneath everything from Joseph Campbell to Bruno Bettelheim to The Wizard Of Oz—that it hardly counted as subtext anymore. But it’s still fundamentally a story about revolutionaries standing up for what’s right, and its Vietnam-inspired origins complicate the notion that Star Wars was ever purely an escapist enterprise. No matter how long ago and how far, far away you set a story, the real world has a way of creeping in.

Lucas borrowed well, and hired even better. He came up with a film-mad generation of filmmakers that included Steven Spielberg, John Milius, and Martin Scorsese, all friends and/or collaborators at various points in Lucas’ career. And then there was the slightly older Francis Ford Coppola, who served as a mentor and partner early in Lucas’ career. Like the others, Lucas borrowed freely. In Star Wars, he combines influences with a brilliant recklessness, refusing to make any distinction between Akira Kurosawa, John Ford, Fritz Lang, David Lean, old serials, and World War II movies, as he took them all to outer space. Star Wars doesn’t hide its influences so much as it melds them beautifully into a coherent universe.

Lucas’ choice of collaborators served him well with Star Wars. It’d be a different movie without any one piece of the team: visual-effects artist John Dykstra (trained by 2001’s Douglas Trumbull), sound designer Ben Burtt, miniature-effects artist Joe Johnston, illustrator McQuarrie (whose remarkable concept art did much to shape the film’s look), or composer John Williams. For evidence, look no further than the film’s original, Williams-free trailer. The eerie score music gives it a feel that’s closer to the moody dystopian science-fiction movies of the early 1970s than to the Star Wars we know:

The film itself offers a clever synthesis of the familiar and the strange. Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) is a common type from a distant planet, a farm boy dreaming of adventure. His enthusiasm for fast vehicles bears more than a little resemblance to the gearhead obsessions of the American Graffiti kids (and the man behind both films). The combination of the strange and the familiar extends to the film’s sound effects, too: Burtt stretched and blended a variety of sounds into uncanny new combinations. He achieved the roar of the Empire’s TIE fighters, for instance, by joining a recording of cars driving on wet pavement to the sound of a trumpeting elephant. It’s all this close to being recognizable, while still far enough removed from the source to seem alien and new. It’s the Star Wars aesthetic in miniature.

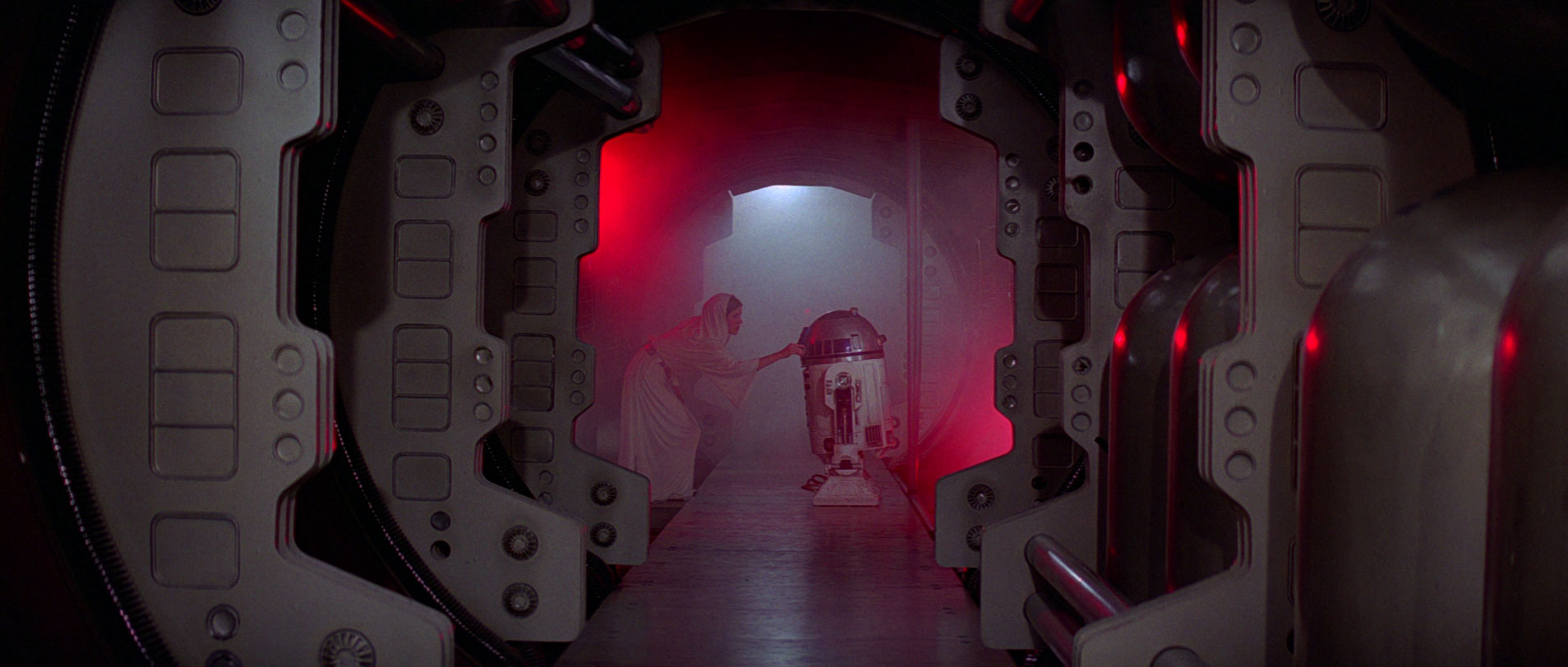

Lucas has long been vocal about looking to Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress for inspiration, though the degree to which he borrowed from it sometimes gets overstated. That film’s bickering peasants Matashichi (Kamatari Fujiwara) and Tahei (Minoru Chiaki)—one tall, one short—provided inspiration for R2-D2 (Kenny Baker) and C-3PO (Anthony Daniels), but at no point do the contentious droid pals contemplate raping Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher), as their analogous characters do in Kurosawa’s film. The smartest element Lucas took from The Hidden Fortress was his decision to begin the film from the droids’ perspective, following the lowliest of the universe’s citizens as they find their way through the chaos of (as the opening crawl states) a period of civil war.

By opening with C-3PO and R2-D2, Star Wars thrusts viewers into its world and counts on them to be engaged enough to figure out what’s going on. Even if Star Wars’ title hadn’t been amended to add “Episode IV,” it would still feel like a story already in progress, complete with talk of a Galactic Senate, a never-seen Emperor, spice-smuggling (an homage to Frank Herbert’s Dune), and a past filled with Jedi. The action stops for the occasional explanation, but more goes unexplained.

Rather than exploring the universe of Star Wars from the top down, Lucas’ film moves from the bottom up, and it doesn’t leave viewers much of a chance to catch their breath or get their bearings. This ends up making it more intriguing than frustrating, as does the grubbiness of the world itself. The Rebels’ ships, Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon, Luke’s landspeeder, the scuffed-up C-3PO, Ben Kenobi (Alec Guinness): They all look like they’ve seen better days, and they all look like they have stories behind them that the film doesn’t have time to tell. Only the Empire gleams, but its malevolent polish suggests tales of its own. The film offers a glimpse at a new world, but it’s enough to create a demand for more.

So why Star Wars? Maybe it’s all of the above. Maybe its something else. Or maybe it’s the rare film whose success defies easy explanation. Credit the zeitgeist. Credit something in the air. Credit The Force. Something about it took over the imaginations of those who saw it, particularly those who saw it young. (As crazy and obsessive a project as it is, Star Wars Minute also seems like a natural extension of many playground hours spent arguing about whether Jawas should be considered good guys or bad guys, and whether Han would be any good with a lightsaber.) The film’s reach extends through toys, comics, games, sequels, and the many films it inspired directly, or which were ushered into production thanks to its success.

Whatever the cause, Star Wars initiated a sea change in big-screen science fiction, beginning a new phase of the era covered in this column, one in which science fiction became bigger, bolder, and more popular than ever. It was also the end of something. In retrospect, it seems fitting that Star Wars followed shortly after The Man Who Fell To Earth. Nicolas Roeg’s 1976 film now looks like the apotheosis of the kind of downbeat, experimental science-fiction art from the first chunk of the 1970s. Star Wars made science fiction bigger than ever, but it also changed the rules: Science-fiction movies now had to work as spectacle first, with every other quality as a secondary consideration. Star Wars didn’t usher in this change alone. Steven Spielberg’s thoughtful-and-spectacular Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, released later the same year, might have had a similar, if lesser, effect without it. But at this point, it’s impossible to imagine a movie world without Star Wars, and in the years that followed, those who wished to use science fiction to say something had to show something first. Some learned to navigate this new world well, some poorly. All now had to reckon, in one way or another, with events that unfolded a long time ago, and in a galaxy far, far away.

Next: Mashed potatoes