Part three: When the well goes dry: Soylent Green, Z.P.G., No Blade Of Grass, Silent Running

Fade out: Charlton Heston dying in a virtually abandoned Los Angeles. After spending much of 1971’s The Omega Man treating the city as a lonely playground, living in isolated luxury as the apparent last man on Earth, he sacrifices himself in a battle against The Family, a vampire-like cult, in order to keep the spark of humanity alive. Fade in: Charlton Heston in New York in the 1973 film Soylent Green. As Detective Robert Thorn, he now faces the opposite problem. Though he lives better than much of the population, simply leaving the apartment he shares with Sol Roth (Edward G. Robinson), the elderly academic who helps him with his cases, means walking over throngs of the less fortunate, who sleep on the staircase outside his apartment and gather in the streets below, wearing frocks and headscarves that make them look more like 19th-century peasants than 21st-century residents. It also means plunging into air thick with yellow smog, which bathes the surroundings in a sickly haze. Unlike The Omega Man’s Neville, this Heston hero will never want for company. There are people everywhere.

But there’s no space, and even less food. While a few live in privilege, most want for everything, trading scraps of credit for processed food products made by the Soylent company, items like Soylent Red and Soylent Yellow, made of “high-energy vegetable concentrate.” And on Tuesdays, they can trade that credit for the new, much-in-demand Soylent Green, “the miracle food of high-energy plankton, gathered from oceans of the world.” There’s no mistaking it for the real thing, but New Yorkers of Thorn’s age and younger don’t remember much of the real thing anyway. It’s a world where someone with the money to pick up a single jar of strawberry jam needs to explain how she got the resources. The bounty of the world, which once seemed inexhaustible, has dried up.

In creating the world of Soylent Green, director Richard Fleischer and screenwriter Stanley Greenberg drew from Harry Harrison’s 1966 novel Make Room! Make Room!, which ran to the bitter end with the idea of overpopulation becoming a problem. The film’s release coincided with widespread concern about overpopulation and environmental abuse, three years after Richard Nixon created, by executive order, the Environmental Protection Agency to fight against the detrimental effects humanity was having on the planet. (Earlier in 1970, he put the need for it in no uncertain terms, saying in his State Of The Union address, “The great question of the ’70s is, shall we surrender to our surroundings, or shall we make our peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land, and to our water?”) Soylent Green opens with a how-it-came-to-this montage that begins with charming scenes of people enjoying nature, then escalates until it’s filled with stock footage of churning smokestacks and car-choked freeways. Such images would be familiar to nightly news viewers or readers of Time magazine, which in February of 1970 ran an extensive cover story titled “Fighting To Save The Earth From Man.”

In the 2022 of Soylent Green, the battle has already been lost. And though the film has largely been reduced in the collective consciousness to the dark punchline of its famous (and famously parodied) final scene—do I even have to spoil it?—it would be chilling even without that revelation. At heart a detective story, Soylent Green finds Thorn investigating the death of William Simonson (Joseph Cotten), a Soylent executive bludgeoned to death in his luxurious apartment, in what’s supposed to look like an ordinary break-in. Thorn suspects otherwise, and he stays on the case, despite receiving every encouragement not to. Besides, he kind of has a thing for Shirl, Simonson’s live-in concubine, played by Leigh Taylor-Young. By the law of the day, she stays with the apartment until the next owner decides whether he wants to keep her around.

The investigation lets Soylent Green show what the world has come to a little bit at a time. As a cop, Thorn has access to both the highest echelons and the lowest reaches of society, and the film shows the many ways in which the two are connected. The definition of a journeyman director, Fleischer is in top form here, sitting back and taking in the world of the film—its choked streets, its sterile luxury, the widening gap between the two, and the way one would be impossible without the other. (Its best moments anticipate The Wire.) Thorn begins the film cynical about the system, then learns just how corrupt it’s become, and how difficult it would be to change. It’s a dying animal that’s started to consume itself.

Then there’s that remarkable ending, which climaxes with Thorn’s breathless revelation about the true nature of Soylent Green, but takes the long way to get there. Sol beats Thorn to the discovery, and responds in the only way that makes sense to him, walking to the nearest voluntary-suicide center and claiming his reward for willfully offing himself: 20 minutes in a room lit by his favorite color (orange) and images of nature projected on a Cinerama-like curved screen and scored to his favorite music (light classical).

This moment—all the more touching because it’s Robinson’s last role—makes it clear just how far the world has fallen. Thorn can barely comprehend the images of unspoiled nature that send Sol into ecstasies. But Sol understands what he’s seeing. He also knows it’s gone, and never coming back.

****

There’s a similar scene in Z.P.G., a little-seen British science-fiction film from 1972 directed by Michael Campus (who had a hit in a different genre with the following year’s The Mack). In a movie theater, crowds watch footage of 1970s families picnicking and eating from tables sagging under piles of meat and cheese. The narrator cautions that the people being shown were “almost criminally addicted to food,” which they consumed “irrespective of its nutritive value” and “in huge quantities.” Fortunately, in the world of Z.P.G., nobody has the chance to overindulge. Everything is strictly regulated, from food to living quarters to recreational activities. And in the film’s opening scene, the president of “The Society” issues another decree, one forbidding childbearing for 30 years.

Z.P.G. takes its title from the Zero Population Growth movement, which became prominent in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and advocated flatlining the population in order to avoid overpopulation and its attendant drain on natural resources. It takes on a different meaning here. As in Soylent Green, the world has already eroded its resources past the crisis point, and is now taking desperate measures. The human cost is considerable: The new regulation doesn’t erase the desire to have children, but to counter those who would violate it, the government provides a healthy reward for those who turn in parents who gave birth after the passage of the law. Violators are then placed in a plastic bubble and suffocated in public.

The Society recognizes it can’t eliminate the parenting impulse, so it redirects it, providing robot children for those who want them via Babyland.

Despite the highly advanced robotics of Babyland, this isn’t enough for some, like protagonists Russ (Oliver Reed) and Carol (Geraldine Chaplin). One night after making love, they opt not to push the button to terminate any potential pregnancies (conveniently marked “Abort”). This revives the couple’s troubled relationship but also invites a world of trouble as they attempt to hide Carol’s pregnancy, and then their son. Their occupation doesn’t help. Employees at the State Museum Of Nature, a facility filled with taxidermied animals of extinct species (such as turtles and cats), they’re expected to play a role in one of its exhibits by acting out a simulation of everyday 20th-century life, including tension and infidelities, with another couple. When their partners learn of the child, they agree to keep quiet about it in exchange for some access to the baby. Then their bargaining takes a harder turn, forcing Russ and Carol to consider desperate measures.

Co-written by Max Ehrlich and Frank De Felitta, Z.P.G. doesn’t offer a deeply considered world à la Soylent Green, a film which suggests it was thought out beyond the details that made it to the screen. In fact, Z.P.G. is sometimes amusingly literal-minded in the way it sees its concepts through, from Babyland to its frequent references to the 1970s as a turning point. It was also made within obvious budgetary constraints that are only partially obscured by the mist that constantly covers the set. That might explain why it never found that wide an audience, despite being derived from the anxieties of the times. When it played New York as part of a double bill with an equally forgotten Jacques Demy adaptation of The Pied Piper (starring Donovan!), the Times’ Vincent Canby could barely spare a few words for it, beyond dismissing it as “a sometimes funny (unintentionally), untimely meditation on the earth’s over-population problems, set in some future smog-bound England.”

While it’s true Z.P.G. sometimes comes this close to turning into a parody of dystopian science fiction, its simplicity suits it most of the time, giving the film a hazy, dreamlike quality that’s only reinforced by Chaplin and Reed’s muted performances. It’s also convincing in its depiction of a society driven collectively mad by a downward turn in fortunes. (Its depiction of the madness that might enter a society that has forgotten what a baby’s cry sounds like resurfaced in Alfonso Cuarón’s Children Of Men, whose final scenes echo the end of Z.P.G.) Maybe it plays better now than it did then. It’s a humbly scaled vision of a world nobody would want to live in, but its intimacy and its emphasis on the deleterious effects living there has on one couple make it feel immediate, clichéd jumpsuits and all.

***

Where Soylent Green and Z.P.G. depict societies turned repressive by the lack of resources, 1970’s No Blade Of Grass suggests that a similar situation might lead to the breakdown of any kind of order, repressive or otherwise. And quickly, too. Co-written and directed by actor-director Cornel Wilde, No Blade Of Grass depicts the chaos that ensues when a plague—with roots in pollution—turns grass poisonous. An eyepatch-clad Nigel Davenport stars as John Custance, a former soldier who, after receiving a tip that London is about to be closed off, gathers his family and attempts to make his way to Scotland, where his brother has a farm and has promised safe harbor should such a thing happen.

Their travels aren’t smooth. As John makes his way north with his wife Ann (Jean Wallace, Wilde’s wife), his teenage daughter Mary (Lynne Frederick), and Mary’s boyfriend Roger (John Hamill) in tow, their first stop is to retrieve his son David (Patrick Holt) from boarding school. Along the way, they encounter urban rioting and rural roadblocks, and John deals with every situation like a soldier, considering the interests of his unit above all else. And though Wilde is far from subtle as a filmmaker—one early scene shows characters watching reports of famine, complete with images of starving children, on a television mounted above a luxurious buffet—the film quickly enters a moral grey area. When John reaches a farmhouse and asks for food, he doesn’t think twice about killing the residents who refuse his help. His survival depends on it. So what if his victims are guilty of nothing worse than protecting what’s theirs? (Besides, it isn’t like they’ve resorted to cannibalism as others are rumored to have done—shades of Soylent Green.)

Much of No Blade Of Grass plays out like Lord Of The Flies, but with all of Britain serving as the island, and the adults devolving into savagery without the excuse of not being old enough to know better. It isn’t a great movie by any stretch. Wilde lays it all on awfully thick—a scene in which bikers rape some members of John’s family while the soundtrack blares “groovy” rock music is a particular low point. But Wilde’s unblinking approach to violence and refusal to decide whether John is a barbarian or merely a pragmatist makes it distinctive and unsettling. The setting helps as well, playing its breakdown of civility against a backdrop of cozy villages and rolling English fields, a place where such things are supposed never to happen. “Keep up your Latin. It’ll stand you in good stead,” David’s teacher tells him while saying goodbye, unable to imagine a time when it won’t.

In the Montreal Gazette, critic Jacob Siskind wrote of “still quivering” hours after seeing the movie. He warned, “the whole thing is frighteningly real, and before the picture is over you get the feeling that this may all happen to you too.” As with Z.P.G. and Soylent Green, the film’s urgency remains palpable. It’s the product of a moment when many had convinced themselves that the world was on the verge of going round a bend from which it would never return, if it hadn’t already. “This motion picture is not a documentary,” a narrator says at the film’s end. “But it could be.”

****

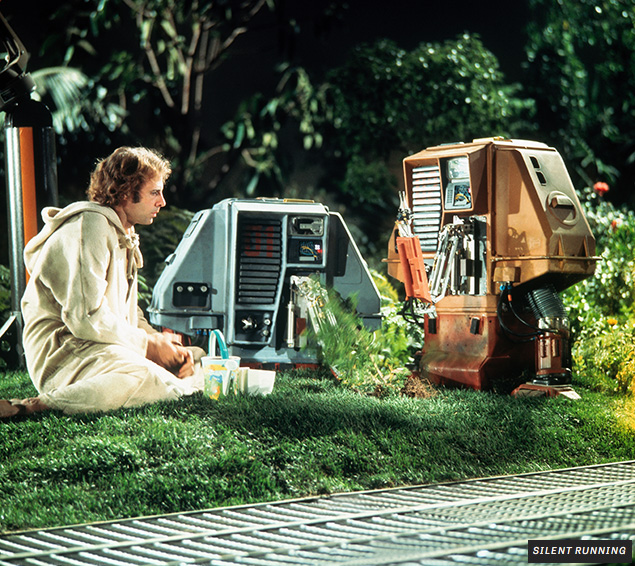

No one would ever mistake Silent Running—the first film directed by special-effects expert Douglas Trumbull—for a documentary, but it’s just as much a product of the same pessimistic moment in movie science fiction that produced the films covered above (and the different strain of dystopian science fiction to be covered in next month’s column). Earth has become inhospitable to plants, prompting part of the population—shades of Wall-E, whose director acknowledged the influence—to preserve what remains in the cold comfort of a floating caravan. Some remnants of the old life on Earth have survived, however. A few ships, including one overseen by the symbolically named Freeman Lowell (Bruce Dern), contain domed greenhouses filled with what remains of Earth’s plant and animal life. For now, at least: When Lowell and his crew receive news of an important message, Lowell expects it will be a promotion. Instead, they’re told they’ll soon be abandoning ship and letting loose their precious cargo. Because who cares about plants anymore, anyway?

Not Lowell’s crew, who treat their jobs as just that, and seem eager to return to the rest of the world. But Lowell does. And in an act of defiance—which involves killing his shipmates—he decides to stay on board and live with the plants, the animals, and the Drones, three robots he dubs Huey, Louie, and Dewey. (Dewey gets destroyed before he can learn his name.) Alone with his robot friends—Mystery Science Theater 3000 creator Joel Hodgson has also acknowledged the film’s influence—Lowell tends to the plants, teaches the drones to play poker, and, though haunted by his crimes, generally seems happy just to tend to the remnants of Earth and instruct the sometimes-clumsy Drones in doing the same—occasionally, as Joan Baez sings approvingly.

With the ill-starred Brainstorm, Silent Running is one of only two features Trumbull has directed. (To date, at least. His website suggests plans for future projects.) He dreamed up the story, then handed screenwriting duties over to Michael Cimino (then making a name for himself as a screenwriter), the screenwriter of Cimino’s The Deer Hunter, and Steven Bochco, future showrunner of Hill Street Blues, L.A. Law, and Doogie Howser, MD, among others. Whatever the other writers brought to the project, Silent Running is a beguilingly simple film. Dern plays Lowell as a wide-eyed hippie who truly cares about the environment, no matter how little anyone else does, and the story doesn’t develop much beyond finding ways to illustrate that in scene after scene. It’s also a tremendous showcase for Trumbull’s effects work—imposing spacecrafts, the uncanny image of a domed forest floating in space, and the childlike Drones. Lowell’s scenes with the Drones—played by amputees—are unfailingly moving. They feel like the creation of a man who’d learned to express himself through machinery.

Trumbull worked extensively on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, particularly its climactic Star Gate sequence. (Prior to Silent Running, he also worked on The Andromeda Strain, and he later did similarly remarkable work on Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Blade Runner, and most recently, The Tree Of Life.) British critic Mark Kermode, who’s regularly called Silent Running one of the greatest movies ever made, praises it for its unabashed sentimentality and heartbreaking qualities, and recalls Trumbull telling Kermode he wanted to make a film “about people.” Calling it the “yin to 2001’s yang,” Kermode suggests it was made in response to the “lack of humanity of 2001.” He isn’t entirely wrong. Silent Running is an unabashedly openhearted film that suggests viewers recognize the wonders of the Earth before it’s too late, a movie about a committed ecological protector and the tiny metal pals he fosters.

But it’s also this: A film about a man so disenchanted with humanity and of living on an Earth that’s lost its natural resources and all their beauty—even while virtually eliminating illness and unemployment—that he turns his back on it in favor of plants, animals, and robots. There’s a coldness to 2001, but at heart, it’s concerned with humanity—its past and its destiny. Science fiction doesn’t get much warmer on the surface than Silent Running, but that warmth swaddles a misanthropic heart. 2001 ends by putting a question mark next to the future. In Silent Running, the future looks like a long, dull epilogue, one in which life goes on, but hardly seems worth living. Lowell wants to save what’s left of Earth, but he also recognizes he’s a custodian for its final days. Recognizing the end is near, he responds in the only way that makes sense to him: doing the best he can as it all winds down. He’s alone in space, but many of those watching from Earth undoubtedly saw a bit of themselves up there.

Next: The early-1970s dystopias of A Clockwork Orange, THX-1138, and other films.