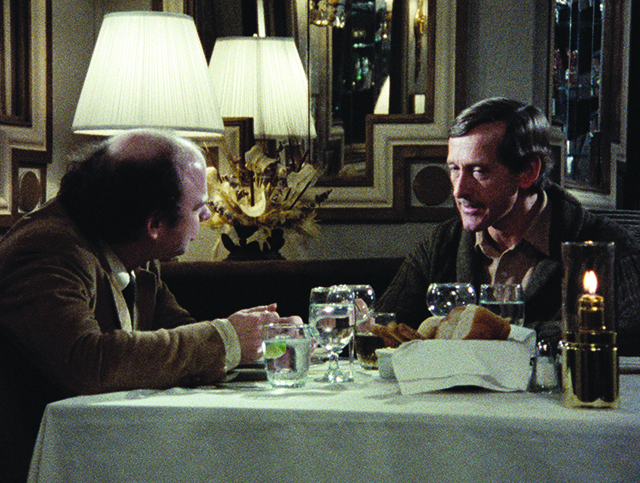

The Criterion Collection is recognizing two men who had a phenomenal impact on the American theater, but in this case, it’s their contributions to cinema that are relevant. Avant-garde director André Gregory and playwright Wallace Shawn worked together on experimental stage productions throughout the 1970s, but became better known outside New York City when they collaborated on a scripted conversation that filmmaker Louis Malle turned into the 1981 arthouse hit My Dinner With André. A winding, amiable chat between an adventurous artist (based partly on Gregory) and an urban neurotic (based partly on Shawn), My Dinner With André impressed audiences around the world with the boldness of its conceit and the quality of its discourse, which covers everything from a world traveler’s wild spiritual quests to an apartment-dweller’s appreciation of life’s simple pleasures. Gregory, Shawn, and Malle collaborated again a decade later on 1994’s Vanya On 42nd Street, which was drawn from a version of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya that the cast had rehearsed off and on over the course of three years, in a crumbling Broadway theater. And in 2014, Gregory and Shawn tackled Henrik Ibsen with director Jonathan Demme in the film A Master Builder.

All three movies have now been collected in the Criterion box set (Blu-ray or DVD) André Gregory & Wallace Shawn: 3 Films. More than just exercises, the films are a document of their creators’ personalities and preoccupations, capturing how they’ve spent much of their lives trying to transform their audience’s understanding of the theater without disrespecting its classical traditions. Gregory and Shawn spoke separately with The Dissolve about the origins, philosophy, and legacy of their movies, and how they fit into their larger careers—including Shawn’s work as a character actor and voice actor. (He’s familiar to millions as Rex the dinosaur in Pixar’s Toy Story movies.) The two interviews have been edited together.

The Dissolve: Did A Master Builder take as long to develop as Vanya On 42nd Street?

Wallace Shawn: A Master Builder probably had the longest rehearsal of any theater project we’ve ever done. We started rehearsing in 1997, and I believe we filmed it in 2013, so… many, many years of experience in rehearsing that play. Well, only the older people rehearsed from 1997. Myself, Julie Hagerty, and Larry Pine. They’re now grandparents.

André Gregory: I would say that there was less improvisation in A Master Builder, but basically, the way it worked was very similar.

The Dissolve: In terms of gathering people and doing it over and over?

Gregory: Gathering people and working toward going deeply into their psychology, getting the actors to show parts of themselves they’re not used to revealing. A Master Builder was a much harder script to decode than Vanya. The reason we rehearsed Vanya for so long was that it took a while to reach a conclusion in the work that I felt was true to the actors, the play, and me. But really, we’ve always rehearsed for a long time. Wally and I rehearsed My Dinner With André for nine months before Louis Malle came onboard. I think probably I rehearse longer now than any director in the world.

The Dissolve: Were there public performances of A Master Builder like there were with Vanya?

Shawn: We don’t say “performances,” because, well… That word shouldn’t be used. We did open rehearsals of both plays for invited, non-paying audiences.

The Dissolve: What’s the main advantage of working in this way? What does it help the actors bring to the material?

Shawn: I know Stanislavsky worked for many, many years on his plays. And the Berliner ensemble of Brecht worked for a very long time on those plays, and I believe it’s fair to say they never considered them completed, exactly, but would continue to work on them. André was inspired by all those people, although we never set out with the intention of rehearsing for such long periods. With Vanya, I think we never planned to perform the play at all. It was just about work, exploration. With the Ibsen, we thought it could be done rather quickly and easily. But there was more that needed to be understood before André felt we were ready to show the play to people. You don’t want to show something to people if it’s incomplete, or if there are long passages where nobody knows what they’re doing. Ordinarily in theater, there’s a deadline and an opening night, and you have to do it by then. But André has managed to avoid working with deadlines, for the most part.

Gregory: Well, when you’re dealing with works like these that are so complex and so deep, the writers took years to complete their scripts, so why be so disdainful as to only work for six weeks on trying to reach the same depth they did? Plays are not literature. What a play is about is not visible on the surface. A play is a skeleton for production, just as a screenplay is a skeleton for a film. In order to put the meat on the bones, you need to at least take the time the author took. One man who invested in one of my works—a millionaire businessman—said to me, “Why do you have to take so long?” And I said, “If you were making cars, would you put the car on the road before you really knew it could run and last?” The theater is generally dictated by economics. People rehearse for a month or six weeks because that’s all they can afford. But a writer might take years to complete a novel, so why not do the same thing in the theater?

The Dissolve: Does this process appeal to you more as an actor, a student of the theater, or a director?

Gregory: Well, my real calling is as a director. I only act every once in a while, and rarely write. My calling is as a director, and this process appeals to me as a director, because when you look at a Wallace Shawn play or at a Chekhov play, you can’t have an idea about what it’s really about. I think the mind only enters the process at the end when you’re shaping and editing. Until you reach the end period, you’re going by intuition and instinct and gut. And you go in many directions that turn out to be dead ends.

The Dissolve: Is there part of you that would still like to be rehearsing Vanya and A Master Builder?

Gregory: No. I got to a point where I finally felt, “This is what I want to say. This can communicate with an audience. It is, in fact, finished.” I now draw a lot. I just had an exhibit at a very nice gallery in New York. One of the challenges in drawing is knowing when it’s finished. It’s the same thing with a play. You have to know when it’s finished.

Shawn: I loved working with those people, so I miss that. I never liked playing the part of Vanya very much. But yes, I mean, if you said to me that there would be more rehearsals of that play, that’d be great. I’d be happy about it. I’d love to work with those people again, and why not on those plays? But I found the part of Halvard Solness more enjoyable than the part of Vanya.

The Dissolve: Why?

Shawn: Actors are, in some cases, people. I suppose as a person, you don’t have to actually be the character, you’re just playing the character. But I would rather spend eight hours as a dangerous megalomaniac than eight hours as a pitiful person who is repulsive to the woman he loves. In real life, it’s probably better to be the pitiful and repulsive person rather than the megalomaniac. But theater is not real life.

The Dissolve: Do you have any plans to do another project like Vanya and A Master Builder somewhere down the line?

Gregory: I’m thinking of one that I can’t really talk about right now. But having just turned 81, I certainly can’t rehearse it for 14 years. Drawing has become such an obsession for me. And I’m also writing a memoir, so I’m pretty busy creatively. I can’t tell right now whether I’ve got a theater adaptation up my sleeve, but I might.

The Dissolve: What were the differences between working with Louis Malle vs. Jonathan Demme?

Shawn: Jonathan Demme is a lot wilder and more prone to fits of inspiration, and he’s improvisatory. Louis was more systematic and careful. Jonathan Demme is a risk-taker.

Louis spent months with us on My Dinner With André, so it was incredibly well-rehearsed in terms of how it would be filmed. He knew exactly what he was going to do before doing it, with a few alternatives. We had a three-week shoot. The first week was spent doing tests, and Louis tried out different ways he might want to move the camera. But he eventually abandoned all the experiments and tests, and there was very little movement of the camera. But he knew exactly what he was going to do. Vanya, he really couldn’t know, because the way we rehearsed with André, we did it differently every time. I think the filming of Vanya had more surprises in it for Louis, but still, he did try to do it in a sensible way, and was thinking of how he was going to solve the problems in the editing room while he was shooting it.

Jonathan actually did something no director would do, and said we didn’t have to do it the same each time. We could do it from different angles in different ways. And I don’t know how he and the editor dealt with that. But when you see the movie, you wouldn’t know. Somehow, he channeled our spontaneity without making it look like it doesn’t cut together.

Gregory: What they both had in common that they were very passionate about the theater work itself. They’re both very fine directors. They were both very nice guys, easy to work with, and great collaborators. Both were enormous fun on the set. Both were directors who had crossed between fiction and documentary. What they had in common with me is that neither of them like to talk about the process very much. They just liked to do it.

The Dissolve: Do you see them as having left authorial stamps on the work?

Gregory: I would say they were part of the team. You could say Vanya really is a Louis Malle film, and A Master Builder really is a Jonathan Demme film, but they weren’t imposing anything to show off. They’re both very modest men, so they made their work subservient to what I’d done, while at the same time adding a strong wash of their own.

The Dissolve: What are other examples of really well-done filmed plays?

Gregory: In a way, the closest is Ingmar Bergman, even though he wasn’t making films out of theater pieces. He was such a man of theater, and he used actors who could be excellent in both media. I think A Master Builder in spirit is very close to Bergman. I can’t think of many other examples.

In my case, I’m a theater director who hates to go to the theater and loves to go to the movies. [Laughs.] If I could make movies, which I don’t want to, I would be making movies. Also, if you spend years on a theater piece and you play it in very small spaces, you like the idea of reaching a larger audience with your work. But I now don’t think of either Vanya or A Master Builder as a movie of a play. I see them both as movie-movies, even though they were quite faithful to the original theater piece.

Shawn: I remember a film Alain Resnais did of a rehearsal of a play, and I don’t remember the name of it [Probably either You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet! or Life Of Riley —ed.], but it was fantastic. Usually, though, it’s a very, very awful thing to see films of stage performances, because most stage performances were intended for the stage, and to have possibly hundreds of spectators. The scale is all wrong. If the same actors are involved, all of the memories in their body are absolutely wrong, to the point where you feel, “Oh my God, these actors are terrible.” And if you ever see a filmed play that is a real performance in which you see the audience or you hear the audience, it’s an absolute nightmare. You hear people laughing and you can’t see anything remotely amusing about what you’re looking at, because it’s not intended to be filmed.

The Dissolve: When you were working with Malle and Demme on these films, how did you adjust them so they’d be cinema and not just performance pieces?

Shawn: We had never performed them, really. Maybe for 20 people. And even in those performances, we wouldn’t have been right for film. It’s true we weren’t trying to scale ourselves down from having performed for 500 people, but even for 20 people, it’s surprising what you can get away with that would be ridiculous in a movie.

The Dissolve: How did you know? Were you looking at rushes and then tweaking, or did you just have an intuition of what would look right onscreen?

Shawn: When we rehearsed My Dinner With André, we did rehearse on video quite a bit, and Louis would show us what we’d done. And all of the actors in both the Ibsen and in Vanya had some familiarity with film, so yeah… We could sort of tell.

The Dissolve: Do you have a preference between theater and cinema?

Shawn: Do you mean to see, or be in?

The Dissolve: How about both?

Gregory: I think each medium is about as different from the other as sculpting is to music, or theater is to sculpting. They are completely different. I happen to think I may be a great director of theater, but I wouldn’t even know how to begin to shoot a film. The sense of time is very different. Film is musical in a very different way from theater. Also, I just got my first iPhone two years ago. I have no sense of technology whatsoever, and it bores me. I’ve sat in on the recording sessions and the editing for our films, and it just bores me. I have no gift for it. I think I have a real gift for theater.

Shawn: I personally am something of an addict in regard to theater. I do actually love to watch actors perform, and I like to watch plays. It’s much easier to go to a film. They say many people don’t go to films anymore, just like people used to say that theater is dying. But it seems that most people I know watch films on screens at home, which is fine for some films. For others, you miss a lot. I find I remember plays better. I remember plays and performances going back to my childhood. Films often completely disappear. I don’t remember what they were about, or they make a weaker impression.

It’s more challenging in some ways to be in a play, because you have to remember the whole thing, and you have to go from the beginning to the end, and you have to make sense of the character’s whole story. You can’t go back and do it again, and you can’t make any mistakes. It’s quite challenging. Film is more fun to act in, because the boring aspects of trying to make your voice and your words audible to a lot of people is not an issue in film. It’s their job to make people hear you. You can just talk in a normal tone of voice, and that’s much more fun for me. Roughly speaking, I have found being onstage more frightening.

The Dissolve: What about voice acting?

Shawn: Well, voice acting is a whole other discipline. I’ve been very lucky in getting work as a voice actor even when people may have a low opinion of my abilities, or just not find me very appealing as a human being. I seem to have done rather well as an animal, for some reason. But of course, a great deal of the fun of acting is to act with the other actors, and you don’t do that in voice work. You’re alone in a little booth, like someone going to outer space in a spaceship.

The Dissolve: When people hear your voice in public, do they turn around? Are they familiar with your voice from the Pixar movies?

Shawn: Some people do, yes.

The Dissolve: Children?

Shawn: Not really. There is an occasional kid with a very good ear, but usually, it’s the parents who say, “Oh, my son would like to take a picture with you.” Usually, the kid looks totally puzzled, and the parent has to say, “His voice was used in the cartoon.” And the kid is looking totally blank.

The Dissolve: Although it makes sense to have all three of these films in the same box set, do you actually see My Dinner With André as being of a piece with the other two?

Shawn: I don’t know. It’s not really of a piece, but in the tomb of an emperor, they might put a crown. They might put a bone of a dog that the emperor had been fond of. They might put his favorite sweater. These are all things that aren’t really in the same category, but they all stand as monuments to that emperor. André and I made these three films, and it’s a kind of monument to our collaboration. Those other two works are based on great plays written a hundred years ago, and My Dinner With André is an odd, one-of-a-kind piece that takes off from our own actual lives. But yes, we made these three films together, and that’s the reason for putting them in the box.

Gregory: Well, they were rehearsed similarly. And My Dinner With André was created by two men of the theater, and its subject matter is rooted in theater. It was never intended to be anything other than a movie, but I still think it’s connected to the other two. Certainly the style of acting is similar, because the acting in all three is, I think, my favorite kind of film acting, which is utter simplicity.

The Dissolve: Can you explain what that means?

Gregory: When you act in a theater, you often have to project artificially because you’re reaching a large audience. I only perform for very small audiences in the theater, and the reason I do that is because I feel that film and television have changed our way of perception. We’re used to looking in close-up. And looking in close-up can become very artificial if the actor starts eating up the scenery or exaggerating in any way.

What I like about simplicity is, if you work on it for a long time, it hides a lot of subtext. In that sense, it’s like an iceberg. You only see the tip of the iceberg. You don’t realize there’s a mountain underneath it. Now if you go to a dinner party, everyone’s talking casually about movies and the news and eating, and it looks very simple, but if you could look into people’s hearts, you might see that one couple is about to split up, or that another person has become a drug addict. There’s a lot of subtext at that table, which you can only sense. Nobody’s telling you that it’s there. The simplicity of great theater acting and great film acting always suggests much more than it actually shows you.

The Dissolve: Do you think My Dinner With André would work as a play?

Shawn: It was never thought of as a play. It was always thought of as a film. I would’ve said it couldn’t be a play, but people have done it in Europe as a play, and they seem to like it. There have been some quite successful productions of it. I would’ve said no, because it’s awfully static to have two people sitting at a table for two hours. That would seem intolerable. But I saw it once. I think it was a Dutch production, and they cooked a whole meal, and the actors ate it. The fact that the actors just sat at the table was compensated for by a very active simultaneous thing going on in the kitchen, where there was no dialogue, but a lot of actual cooking.

The Dissolve: As an acting exercise, similar to how you rehearsed the Chekhov and Ibsen over many years, do you think you could perform My Dinner With André verbatim right now?

Shawn: It would be the equivalent of people in their 50s performing Romeo And Juliet. It would be odd as far as our ages were concerned, and some of it would seem absurd. But I suppose if we wanted to, we could.

Gregory: Oh, I think I could do it easily. If I were trying to imagine who I actually was then, that would be impossible. But because it’s a role, it’d be as if you played Hamlet 30 years ago and then you played him again. You might even come up with new stuff you never thought of back then.

The Dissolve: Here’s a variation on that question: If you were to make a new My Dinner With André today with a new conversation, would the subject matter and your personalities be similar to what they were back in 1980?

Gregory: Oh not at all. For one thing, the guy in the movie talks very fast, which I don’t. And he talks at you, while I tend to talk with people. And that guy is a raging narcissist who only likes to talk about himself and his own ideas, while I think I’m much more focused on the other person.

Shawn: It’s very, very much of its time. Even though it has some intense moments and some angry moments about the world as it was back then, I think both André and I have become politically much more radical since those days. Well, I don’t want to talk for André. I shouldn’t say anything about him in regard to that. But I wasn’t as angry then. Now, I wouldn’t be able to have a conversation for more than 15 minutes without getting into a discussion of the world that we live in that would be somewhat more explosive than the things that I said in the film.

The Dissolve: Do you think of the person in My Dinner With André as you?

Gregory: It’s a character based on me. We selected certain parts to make fictional. When you see the movie, you may think the André character is never at home, and you may ask, “What about his family, his wife and kids?” The reality is that I was not away that much. We chose a lot to subtract or not talk about. Another example is, I worked a lot with African-American convicts in halfway houses back then. We left that out because we wanted me to seem more irresponsible. It’s what we don’t say that makes me into a character, to some extent.

I also used four completely different André voices in the performance, to show four different aspects of my character. So it is definitely just a character, inspired by me.

Shawn: I was intentionally drawing a portrait of my character as a complacent, bourgeois person. In some ways, I’m still a complacent, bourgeois person today, and in some ways, I wasn’t really one at the time we made the movie, but was merely playing one for the sake of the story. All the same, if we two Americans were having a conversation now, things like the possibility that America is the enemy of humanity would be raised. And the totally demonically evil system we live under would be discussed more than it was in the film, which was made in a Jimmy Carter era that was intellectually rather bland for people like me. Let’s put it that way.

The Dissolve: Going strictly by the description, My Dinner With André sounds dry and even pretentious, and yet something about it captured the public imagination. You drew an audience who saw it’s actually a lively film. What do you recall about the reaction back then?

Gregory: I thought nobody would go see it except our relatives and a handful of friends, and I was staggered and stunned by the huge response. I still don’t quite understand it. We hit some kind of chord. But it wasn’t just that time, because the film keeps living on. I know that involved in the film is the great art of storytelling, and everyone loves a great story. Another aspect is that there is such a thing as passive art and active art. Passive art tells you what to think and what to feel. Active art allows each member of the audience to think and feel whatever they like. And the imagery in My Dinner With André opens the imagination of each different member of the audience in a completely different way. Nobody sees the burial at Montauk in the same way. Nobody sees the camel ride through the Sahara the same. In that sense, My Dinner With André is as big as Lawrence Of Arabia, because it takes you to the Polish forest, and it takes you into adventures into the Sahara. Except instead of showing you these adventures with the camera, they allow you to make your own moving picture.

Shawn: It was one of those surprising moments that happen in the life of a few lucky people, where for absolutely no reason that you know or can begin to understand, something you did is suddenly immensely popular. I still don’t understand why. That was an experience I had once, and never again. I was whisked off to film festivals, and sat on the same sofa as François Truffaut. I was treated with incredible respect for two or three years. Strangely, even people in the Hollywood film industry went to that film. It seems hard to picture this today, but it was a big hit in Los Angeles. It was very exciting for me, and a lot of fun. Eventually, I returned to being treated with… I wouldn’t say always with contempt, but without that particular type of respect.

Recently, I had a strange reason for calling the office of quite an important agent in the show-business world. I was sweating speaking to his assistant, and I knew that I might be treated with contempt, and that the assistant would probably have never heard of me, and I would probably not be allowed to speak to the agent. Let’s just say that this wouldn’t have happened for that brief period after My Dinner With André. I was riding pretty high then.

The Dissolve: You still have a steady career as a character actor and voice actor, don’t you?

Shawn: Well, I don’t know what to say. Thank you. I just don’t know what to say.

The Dissolve: Do you not think of your career that way?

Shawn: Well… I’m available. I would be honored to appear. The mysteries of show-biz are way, way beyond me. I don’t know if anybody fully understands why actors go up and down in their popularity. There was a year when I played four characters who died, and I sort of thought, “What does that mean? Does that mean I’m going to die myself this year?” I don’t know. Suddenly, there seem to be many jobs, and then, all of a sudden, there are no jobs. It’s as if everybody got together and decided what they were all going to do. I know it doesn’t work that way. But I don’t know how it works.