The credits for Kevin Smith’s 1994 breakthrough film Clerks include a thanks to Richard Linklater, Hal Hartley, Spike Lee, and Jim Jarmusch, “for leading the way.” Smith’s reverent acknowledgment must not have seemed as incongruous at the time as it does now. The four filmmakers Smith thanked were pioneers of American independent film, who helped inspire every plucky dreamer who made it into Sundance with a grimy, black-and-white labor of love financed with credit cards and money borrowed from mom and dad. Every independent filmmaker owed them, and by the time Clerks hit theaters after triumphing at Sundance, Smith was on his way to establishing his own legend as an independent-film success story.

It remained unclear, however, what kind of filmmaker Smith would become. Was he going to be a working-class schlub happily working the fringes? Would his films haunt arthouses alongside those of Hartley and Jarmusch? Clerks has all the grungy trappings of an arthouse film. It was shot in black and white on a budget so small ($27,575) it instantly entered the annals of independent-film mythology. It boasts a soundtrack of what at the time was adorably known as alternative rock. It’s populated by then-unknowns who look and talk like average people. And it’s driven not by plot, which it treats like a regrettable nuisance, but by an infatuation with conversation as a form of sparring, an end unto itself.

Clerks explores a specific cultural milieu with anthropological fascination. Smith concerned himself with the indigenous New Jersey slacker, a species he knows so intimately, he came to embody it for the culture at large. Clerks is in many ways a film about nothing—or rather, about nothing more than the pleasure of bullshitting with your buddies as a way of making it through another day. Smith’s debut takes place in a world before the Internet, yet in its appealingly lo-fi, analog fashion, Clerks predicts what the Internet will become: a place where people with too much time on their hands trade dick jokes and observations about popular movies and television shows (specifically Star Wars, the subject of Clerks’ most famous and inspired riff), and exchange suspiciously honed and intricately worded insults regarding sexual preference. The titular clerks are as passive as anyone can be while still technically holding down a service job; they approach their kooky customers from a pronounced distance, as if they’re watching a crazy YouTube video rather than interacting with other human beings. They’re voyeurs in their own lives. (Similarly, Clerks also anticipates the low-stakes, conversational world of podcasting, where Smith, unsurprisingly, currently serves as the titan of his own digital empire.)

Clerks’ enormous charm lies in its homemade quality. It’s the cinematic equivalent of a crudely Xeroxed zine overflowing with youthful passion and typos, a cinematic demo that’s all rough edges and smartass irreverence. It’s not about polish, it’s about self-expression, and for better or worse, Clerks is an unusually pure expression of who Kevin Smith was as a filmmaker and a man.

The paradox of Smith’s career is that he seems to make the same film over and over, with the same kinds of people talking with the same unmistakable rhythms. And yet his filmography is impressively eclectic, including an alternately earnest and snarky exploration of sexual identity and jealousy (Chasing Amy), an ambitious religious satire (Dogma), a gleefully postmodern show-business spoof, (Jay & Silent Bob Strike Back), a raunchy 1980s-style buddy-cop comedy (Cop Out), a mainstream romantic comedy (Jersey Girl), a provocative mainstream comedy in a deliberately Apatowian vein (Zack And Miri Make A Porno), and most recently, a grindhouse horror film with a socially conscious bent (Red State).

One of Red State’s many unexpected qualities is that for long stretches, it doesn’t feel or sound particularly like a Kevin Smith movie. Otherwise, Smith somehow manages to make films in vastly different genres feel identical. Smith is like a grubby bar band that puts out a prog album, a disco album, and a concept album without ever sounding like anything other than a grubby bar band.

Yet all that lay ahead of him in 1995, when Smith leveraged the surprise grassroots success of Clerks into a deal with Universal and its boutique distributor Gramercy to make a mall-centric teen-sex comedy with Beverly Hills 90210 star Shannen Doherty. Mallrats was a modestly budgeted affair by most standards, but for a guy who made an landmark film for less than 30 grand, having access to literally millions of dollars—not to mention the high-powered likes of Stan Lee, Michael Rooker, and the actress from Three’s Company who wasn’t Suzanne Sommers or Joyce DeWitt—must have seemed like an unbelievable windfall, like being handed the keys to the kingdom.

It was Smith’s play for the big time, his version of the randy studio comedies he grew up watching, but it flopped with critics and audiences alike. Mallrats was seen at the time as a major wrong turn in his burgeoning career, a tacky mistake before he righted the ship with Chasing Amy. But time has been kind to Mallrats, and today it seems less like a mistake than like a natural next step in Smith’s curious kinda-evolution as a filmmaker.

On the audio commentary for Mallrats, Smith says Universal wanted a “smart Porky’s” and was so excited by his film, despite having meddled nearly every step of the way, that plans were underway for a Mallrats sequel before it flopped. Universal’s enthusiasm knew a number of limitations, however. For instance, the studio was so concerned about Jason Mewes’ ability to play Jay—half of the duo of Jay and Silent Bob (Smith) from Clerks—that Seth Green was on call throughout filming to take over for Mewes at a moment’s notice. Homemade and authentic was well and good, but it never hurt to have professionals on call in case the slobs from Jersey screwed up.

Mallrats begins with what qualifies as a bold statement of purpose for Smith: a gerbil-up-the-ass joke about “Cousin Walter,” delivered with breezy charm by über-slacker Brodie Bruce (Jason Lee). This was Smith’s way of assuring a dedicated fan base that while he got swept up in an exciting Hollywood whirlwind of money and stars, his commitment to anal-sex jokes remained strong. Nothing and no one could ever get in the way of Smith’s lifelong love affair with scatological humor.

Lee had never had a major movie role before Mallrats. He made his living as a professional skateboarder—a job cooler and more awesome than acting. But he brought to the role of Brodie a miraculous, unprecedented gift: the ability to make Kevin Smith dialogue sound like words human beings might conceivably say. Lee was, and remains, a human Rosetta Stone, able to translate Smith’s bro-banter into human-speak. That superhuman gift is all the more essential considering that, as written, Brodie Bruce is essentially a teeming pile of rotting garbage in human form. He’s a slacker so cowed by his unseen mother that he forces his longsuffering girlfriend Rene Mosier (Doherty) to sneak out of his basement bedroom under cover of night rather than have his mother find out he’s having sex.

Brodie’s cruelty regularly reduces Rene to tears, so shortly before she breaks up with him by leaving his parents’ basement for the last time, she confides that while weeping habitually about their relationship, “I think about people who make decisions that affect our lives, the doctors who make advances in curing diseases, the engineers that design skyscrapers, the guy that maps out a plane’s flight path. I think about how those people are out there every day, making a difference, leading big lives, and how they refuse to be intimidated by the tremendous odds of failure they faced, and how they only concern themselves with peers and company that apply to their goals and noble causes. I think about all that and I cry because I have nothing better to do than to fuck you.”

This monologue is made even more painful by the tremendous effort Doherty puts into it. It’s hard not to feel for her as she tentatively makes her way through this dark forest of phrases and convoluted ideas. It’s difficult enough to memorize dialogue that torturously written; it seems downright cruel to ask even the most gifted veteran actress to deliver those lines naturally, let alone Doherty.

Rene dumps Brodie due to his lack of ambition and unforgivable dudeness. Meanwhile, Brodie’s best friend T.S. (Jeremy London) gets dumped by his girlfriend Brandi (Claire Forlani) after an argument kicked off by a Dating Game-like show called Truth Or Date, produced by Brandi’s glowering, disapproving father Jared Svenning (Michael Rooker). With nothing to do, and all day to do it, Brodie and T.S. head to the mall to kill time and think up ways to sabotage Truth Or Date, which is shooting there. In the process, they run afoul of sneering metrosexual Shannon Hamilton (Ben Affleck), an anal-sex-obsessed jerk who, in the film’s funniest line, tells T.S. and Brodie that he has no respect for those “with no shopping agenda.”

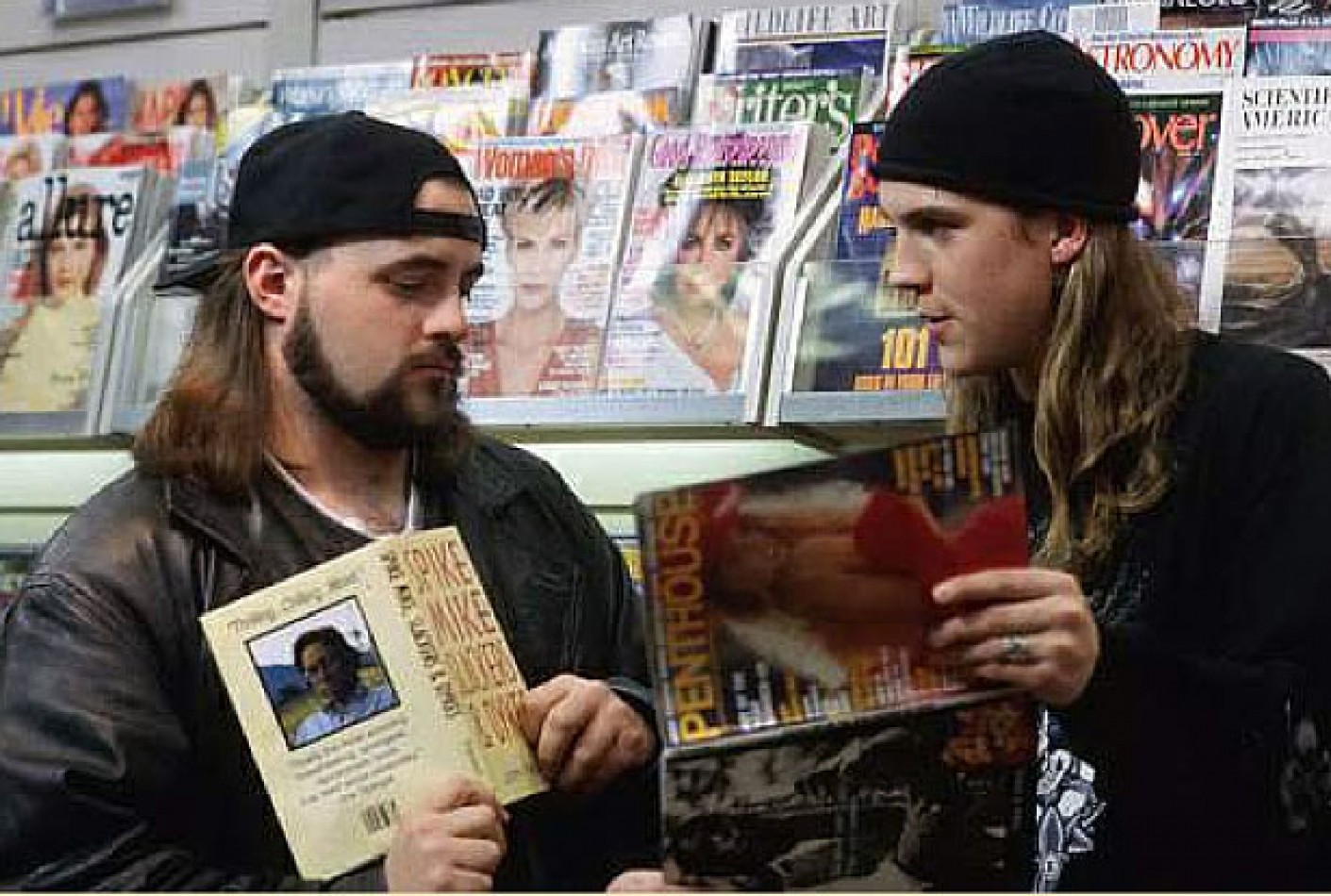

Brodie and T.S. end up joining forces with Jay and Silent Bob, whose unexpectedly MacGyver-like genius for improvising technological solutions on the fly comes in handy during the film’s climax. Jay and Silent Bob have long suffered from overexposure, but re-watching Mallrats gave me a renewed appreciation for the slacker duo. Mewes gives Jay a caffeinated, punk-rock energy that cuts through the droning flatness of Smith’s work, and as Silent Bob, Smith is blessed with a natural screen presence and laconic, easygoing charm. He’s a strip-mall Buddha in a degraded world, an oasis of Zen calm in the midst of a chaotic whirlwind of dick, butt, and boob jokes. Smith is a tremendously likable guy with a winning personality, even though offscreen, he’s cast himself in the Rodney Dangerfield role and every critic in the world in the Ted Knight role, in what he sees as the Caddyshack-style slobs-vs.-snobs comedy that is his life and career.

Mallrats follows Brodie and T.S. as they loiter aggressively and get kicked out of the mall at the behest of Svenning, who is apoplectic that his daughter has been dating such a loser. To get revenge on Svenning, Brodie subjects him to what he calls “stink-palming”—shoving his hand into his butt before shaking someone’s hand. In the audio commentary, Smith quips that he was hoping stink-palming would become a big fad, which it thankfully didn’t. But even though the phrase didn’t sweep the nation, it did contribute to the film’s cult, along with a scene involving a topless fortune teller played by Three’s Company alum Priscilla Barnes, a running gag involving Shannon’s desire to have sex with vulnerable girls “in a very uncomfortable place,” T.S.’ plan to propose to Brandi on the Jaws ride at Universal Studios, and Jay’s borderline-incomprehensible catchphrases like “snootchy-bootchies.” That’s Mallrats in a nutshell: a bunch of random but strangely resonant bad-taste gags and crass caricatures all adding up to something widely beloved within the View Askewniverse—the catchall name for the sprawling, ugly, but weirdly welcoming world Smith has created in his films and comics. Where Clerks boasts a grungy charm, Mallrats is a film of plastic pleasures, a cinematic Spencer’s Gifts hopelessly enamored of its own tackiness. Mallrats wasn’t the cerebral Porky’s Universal was looking for, but it wouldn’t have felt out of place sharing a drive-in double bill with Porky’s back in 1982.

The end credits for Mallrats are fascinating for what they say about Smith and how he saw himself and his films at that curious, uncertain juncture. He thanks independent pioneer John Pierson for “keeping me pure,” which might seem hypocritical coming from a filmmaker following up a low-budget Sundance sensation with a filthy studio comedy involving a naked fortune-teller played by a lesser Three’s Company alum. Yet in its own strange way, Mallrats really does feel pure. It’s nearly as pure a representation of Smith’s sensibility as Clerks. It’s not as if Smith wanted to make an intense character study about a tormented social worker in Watts and his struggles with bipolar disorder, but was roped into making a junky teen-sex romp; this is clearly the junky teen-sex romp near and dear to his heart. Mallrats is an incredibly personal film, except that because this is Smith we’re talking about, that intense personal engagement takes the form of banter about superheroes’ genitalia and winking nods to Degrassi Junior High.

Mallrats also concludes with a dedication, this one thanking, “John Landis and John Hughes—For giving me something to do throughout my youth on Friday night.” In retrospect, it seems a lot more fitting for Smith to thank Landis than it does for him to thank Hal Hartley. Landis went from making homemade comedies guerrilla-style (and, delightfully enough, gorilla-style, in the case of his debut, Schlock) to being one of the biggest commercial filmmakers of the 1980s. If the 1980s-style Mallrats had been the big hit Universal was expecting, it’s possible that Smith might have followed Landis’ trajectory and become a major mainstream hitmaker, making the Coming To America and Trading Places of his generation. But probably not.

Like Wes Anderson and Quentin Tarantino, Smith fills his films with what he loves. But where Anderson’s films can feel like an immaculately put-together museum of their creator’s pet obsessions, and Tarantino’s can feel like a massive cinema archive of the distant past, Smith’s films feel more like a video store where porn videocassettes are stacked haphazardly next to superhero comic books and 1980s videogames, and no one seems to have mopped or tidied up in many, many weeks. Tarantino transforms the trash of his childhood and pop-culture-crazed adolescence into art. Smith transforms the trash of his childhood and pop-culture-crazed adolescence into the trash of today. As Smith’s devoted cult attests, there’s a place for that. There are a lot of folks happy to hang out in a comfy, dumpy place.

Next: Spike Lee, School Daze