“Sometimes it’s a hard world for the little things,” mumbles H.I. McDunnough in Raising Arizona, after awakening from a nightmare (or a vision—he isn’t sure) in which the Lone Biker Of The Apocalypse blows up a fluffy little bunny with a grenade. As Hi speaks, peeking through the blinds of his bedroom window, his wife Ed sings a lullaby to the baby they’ve stolen… except it isn’t a lullaby, it’s a murder ballad. Rather a bleak worldview, all in all, and it’s embedded in what’s surely the goofiest, least serious movie Joel and Ethan Coen have ever made. Even at their most outlandish, they’re still wincing.

It’s taken the better part of three decades for people to catch on to the strain of sorrowful pessimism in the Coen brothers’ work, or at least to grudgingly accept it. For many years, the Coens were dismissed as soulless mimics who looked upon all of their characters with contempt—a cardinal sin in some circles. The same objection had previously been lodged, mostly by the same critics, against filmmakers like Robert Altman and Stanley Kubrick, both of whom shared the Coens’ grim outlook (and who, like them, tended to be unforgiving toward human nature even in their ostensible comedies). Because the Coens have tried their hand at numerous genres, from noir to screwball to outright surrealism, it wasn’t immediately apparent that they were making the same basic movie over and over. After 30 years and 16 features, however, it’s now hard not to notice that prototypical Coen protagonists are hapless, well-meaning schlemiels upon whom life exacts a toll that’s much worse than they deserve. There are exceptions, but even these generally involve loss in some form or another. The Dude’s rug really tied the whole room together.

It would be a fun and possibly eye-opening experiment to find people with zero knowledge of the Coen brothers or the movie world, show them the Coens’ entire oeuvre, and then ask which pictures were wildly acclaimed, receiving multiple Oscars, and which were largely ignored. Judging from arguments that have raged on Twitter, everyone’s ranking of the films is radically different (and the rundown that follows is as idiosyncratic as any, perhaps more than most), but even Joel and Ethan have expressed surprise that movies they thought might be off-putting were instead embraced, and vice versa. What’s truly remarkable is that every one of their films are well worth watching. (Casual viewers can skip a couple that they merely wrote.) Even the consensus choice for their weakest effort features a magnificent lead performance that rescues it from tedium. More to the point, each picture, regardless of personal opinion, fits snugly into a long-term argument that can finally, after all the dull debates about their sincerity or their derisive lack thereof, be clearly perceived.

| 5.0 | Blood Simple | 1984 |

| 2.5 | Crimewave | 1985 |

| 4.5 | Raising Arizona | 1987 |

| 4.5 | Miller’s Crossing | 1990 |

| 5.0 | Barton Fink | 1991 |

Few filmmakers have hit the ground running as hard and fast as the Coens, whose first four features are all within hailing distance of masterpiece status. Joel and Ethan now look back somewhat sheepishly at their debut, Blood Simple—so much so that they re-edited the picture in 2001, trimming one of its clumsiest performances to the bone, and removing other parts they now consider dull and/or gauche. Ignoring the historical ramifications of this decision (it’s now all but impossible to see the original cut; even the VHS version has the wrong music, due to rights issues), they’re out of their minds. Sure, there are spots here and there where it’s possible to glimpse first-timers trying a little too hard to impress, and the film lacks the polish and precision they quickly developed. But their screenplay is among the greatest ever written: a merciless roundelay of deceit, mistrust, and utterly false impressions among a stoic bartender (John Getz), his boss (Dan Hedaya), the boss’ wife (Frances McDormand), with whom he’s run off, and a private dick (M. Emmet Walsh) hired by the boss to murder the lovers. It’s uniquely structured in that the audience always knows exactly what’s happening, but none of the characters have the slightest clue, even though they’re all convinced they’re on top of it. The movie ends with a dying man laughing his head off as he finally realizes the mistake someone else has made—as cogent a summary of the Coens’ personal philosophy as can be found in any of their films.

Joel met Sam Raimi when both were unknowns, and worked as an assistant editor on 1981’s The Evil Dead. During the next few years, while they geared up to make Blood Simple, Joel and Ethan collaborated with Raimi on the screenplay for his second feature, Crimewave, a parody of B-movie thrillers. Allusions to future Coen movies appear here and there: the protagonist awaits execution in the Hudsucker State Penitentiary, for example (the script for The Hudsucker Proxy was already in progress way back then), and a transitional shot that emerges from a trumpet’s horn was re-created in Barton Fink. To the extent that the Coens’ fingerprints are visible in the plot or the dialogue, however, it’s indicative of their weakness for lowbrow comedy, which resurfaced in a couple of their own worst scripts years later. Crimewave’s pleasures are entirely Raimi-inspired, like the priceless whip-pan from a dance contest to the dancers scrubbing dishes (indicating that they lost, as they were trying to win a cash prize to pay for dinner) and the climactic car chase. The verbal jokes are mostly witless, and the story is an incoherent mishmash of barely reconcilable ideas. It did, however, introduce the Coens’ love for bellowing fat men.

As if to prove that they could in fact do comedy, they next made the overtly cartoonish Raising Arizona, about a couple (Nicolas Cage and Holly Hunter, neither of whom was yet a major star) who steal one of another couple’s seven babies (septuplets!) when they discover they can’t have or adopt one of their own. Apart from some showy camera moves and a penchant for florid language—the latter runs through most of their work, and seems to be largely Ethan’s contribution, judging from his published prose—Raising Arizona bears no resemblance to Blood Simple, often looking like a demented live-action version of a Tex Avery short. There’s a core of real pathos underneath the laughs, and sometimes the two are memorably entwined, as when Ed, upon receiving little Nathan Jr., says “I love him so much!” through great shuddering sobs that, as performed by Hunter, are both hilarious and weirdly touching. John Goodman first joins the Coens’ repertory company here, playing an escaped-convict buddy of Hi’s who steals Nathan Jr. himself to collect the reward. The Coens have never made another movie with Cage, which seems criminal, given how perfectly his recklessness meshes with their control-freak exactitude. The movie’s opening 11 minutes (prior to the credit sequence), especially, are a sustained marvel of lightning-quick, gut-busting sight gags, solecisms (“I’m walkin’ in here on my knees, Ed, a free man proposing”), callbacks, and general ludicrousness, all set to Carter Burwell’s peppy banjo score. Given such a virtuosic and diverse one-two punch, it was impossible not to ask: Who are these guys?

Miller’s Crossing niftily ducked the question by shifting the terrain yet again, this time to the intricate, morally compromised world of Dashiell Hammett. Borrowing heavily from his novel The Glass Key, with additional inspiration culled from Red Harvest, the Coens retreated from Arizona’s frenzy into measured stillness; the first shot is a close-up of ice cubes being dropped into a glass, one by one, and while several of the supporting characters are decidedly hotheaded, the film’s overall temperature is cool, taking its cue from watchful, pragmatic protagonist Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne). Like The Glass Key, Miller’s Crossing is fundamentally about the relationship between a misguided criminal kingpin (Albert Finney) and his intensely loyal right-hand man, with Tom achieving all his goals, yet having nothing to show for it in the end. Its signature scene, which is almost too painful to watch, is the one in which bookie Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro)—the first overtly Jewish character in a Coen film, though certainly not the last—begs Tom for his life in a forest clearing, repeatedly pleading “Look into your heart.” What Tom ultimately finds there is none too comforting, and while Miller’s Crossing is brilliant, it’s also overwhelmingly funereal, suggesting as it does that even the things we fight hardest for aren’t worth it.

Miller’s Crossing was such a bear to write, due to its extreme plottiness, that Joel and Ethan got stuck halfway through and couldn’t proceed for a while. During this period of writer’s block, they quickly wrote Barton Fink, in which a New York playwright (Turturro again) gets put under contract by a Hollywood studio and attempts to write a wrestling picture for Wallace Beery from his room in the eerie Hotel Earle. The Coens’ first three films were all tonally consistent to a fault, if anything, but Barton Fink begins in a fairly naturalistic mode, then slowly turns phantasmagorical. Its finale appears to be taking place in the depths of hell, and Barton’s failings as a writer (he’s jejune, pompous, and prone to repeating himself) and as a man (HE! DOESN’T! LISTEN!) land him in a bizarre limbo where his fantasies and nightmares have merged into something inexplicable. By this point, the Coens had become superb technicians, or at least learned who to hire: The production and sound design of the Earle rank right alongside the most creepily atmospheric in the horror genre, with special mention to the vacuum-sealed whooshing noise that accompanies the opening and closing of every door. Still, the movie belongs to Goodman as Barton’s regular-guy next-door neighbor, Charlie. The big lug struggles in vain to tell his new writer friend some funny stories about working-class life (and show him some wrestling moves); he’s ingratiating until he’s terrifying, and equally riveting in both guises.

| 4.0 | The Hudsucker Proxy | 1994 |

| 3.5 | Fargo | 1996 |

| 3.5 | The Big Lebowski | 1998 |

| 3.0 | O Brother, Where Art Thou? | 2000 |

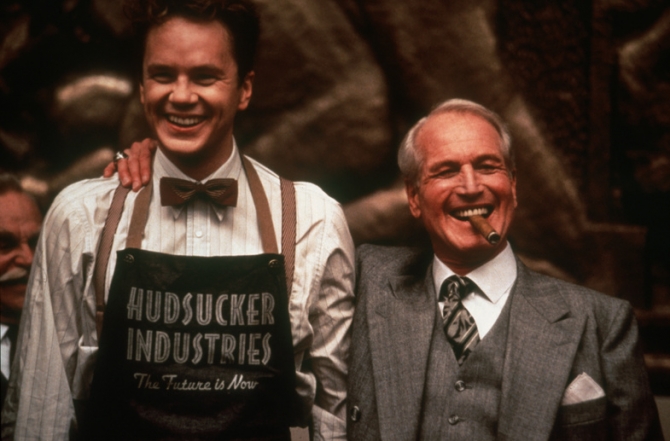

As previously noted, the script for The Hudsucker Proxy (which Sam Raimi co-wrote) had been kicking around for a while, mostly because of the expense involved in making it. With their cultural cachet now firmly established—Barton Fink won the Palme d’Or at Cannes—the Coens were finally able to get Hudsucker financed, and cast Tim Robbins as the naïve Muncie, Indiana native who arrives in New York in 1958 and becomes the designated stooge for a scheming businessman (Paul Newman) who wants the company to fail so he and his cronies can buy all its stock cheaply. The movie tanked at the box office, perhaps because audiences intuited that Joel and Ethan were aping the conventions of screwball comedy without possessing the requisite joie de vivre—this is one instance in which the “soulless” charge had some merit. All the same, Hudsucker is mostly a delight, because the Coens (and Raimi, who directed the superb hula-hoop montage sequence) apparently poured all the cleverness they left out of Crimewave into this screenplay, and also had the budget to make it sing. Jennifer Jason Leigh channels Katharine Hepburn as fast-talking reporter Amy Archer, who poses as a fellow Muncie expat to get in good with Robbins’ Norville Barnes; the film’s atypicality for the Coens is most apparent when Norville learns that Amy is really a journalist and chides her for her deception, saying he can’t believe a Muncie girl would stoop so low. Joel and Ethan didn’t have the right sensibility for such Capra-style sentiment, but it’s still enormous fun watching them give it their best shot, with money to burn.

Up to this point, the Coens had amassed a great deal of respect and a sizable cult following, but they’d never had a big, popular success. It still seems extremely improbable that Fargo was the movie to change that, given its offbeat mixture of tones and its goofy regional specificity. People loved it primarily because they loved Marge Gunderson, the unfailingly sweet-natured pregnant cop played by Frances McDormand (who won the Oscar for Best Actress that year, and married Joel Coen back in 1984). She was the first ray of genuine warmth in one of the Coens’ films, and apparently that’s what had been missing for quite a few folks. What holds Fargo back from greatness is the attempt to juxtapose broad comedy (all the “yaah” business, and particularly scenes like the one in which Marge interviews the two hookers who talk about how funny-looking Steve Buscemi’s kidnapper is, which is metronomic in its timing, and hilarious) with unflinching ugliness, like the lonely, ignored corpse of the innocent person who gets unceremoniously killed as a result of all the idiocy. There are two absolutely outstanding movies in Fargo, but they don’t belong next to each other. The issue isn’t sweet/horrific (that would be fine, and seems to be what was intended), but rather mockable/unthinkable. The Coens tried to integrate their pessimism and their amused detachment, with a hefty dollop of real decency tossed in to sweeten the deal. It worked for most people, but some find it hard to smile at exaggerated “Minnesota nice” in the face of butchery.

If the Coens were surprised that digging into the peculiarities of their home state got them showered with awards, they must have been outright astonished—eventually—that their whimsical tribute to film producer Jeff Dowd, the inspiration for The Dude, became one of the modern era’s biggest cult movies. The Big Lebowski is one of film’s most endlessly quotable films, though few acknowledge that most of its funniest lines and bits come from the first hour or so, with diminishing returns thereafter. Having spent their entire career constructing precise clockwork mechanisms (with the exception of Barton Fink, which gets more surreal as it goes along), the Coens started to worry less about narrative structure with this film, just sort of letting the characters drift where they will. It’s defensible here, given that Jeff Lebowski (as memorably embodied by Jeff Bridges at his most befuddled and exasperated) has no clear direction in life himself, but it does inevitably mean that the movie runs out of gas long before it’s over, eventually resorting to killing off a supporting character for closure’s sake. The Dude’s Zen attitude toward everything except the Eagles holds it all together, though, and people will be saying “I can get you a toe” and “Shut the fuck up, Donny” for decades, if not centuries, to come.

Further emboldened, the brothers decided to make a quasi-musical featuring deeply unfashionable old-time and bluegrass tunes. The result: one of the best-selling soundtrack albums of all time. Also, a pretty good movie, though O Brother, Where Art Thou? is the first Coen film that comes across as a bit half-assed, as if they filmed the first draft. Even more than Lebowski, it feels as if it was made up as they went along, without much attention paid to the big picture. For every delight—George Clooney’s fatuous vanity and obsession with Dapper Dan pomade; Dan Tyminski’s performance of “Man Of Constant Sorrow”; everything Tim Blake Nelson says and does—there’s a corresponding digression that just sits there trying to look Homeric (Goodman as a pseudo-Cyclops) or mythic (the Klan rally). In truth, the movie serves the music, rather than the other way around, so it’s appropriate that the soundtrack wound up being far more successful. Still, O Brother is yet another example of the Coens striking oil with material that on paper seems not just unpromising, but downright off-putting. Remarkable.

| 5.0 | The Man Who Wasn’t There | 2001 |

| 3.0 | Intolerable Cruelty | 2003 |

| 2.5 | The Ladykillers | 2004 |

| 2.5 | ”Tuileries” (included in Paris, Je T’aime) | 2006 |

Whether the Coens read reviews of their films, and whether they take any criticism they might find there to heart, isn’t known. The brothers aren’t especially reclusive, and have done plenty of interviews over the years, but they do avoid saying much that could be construed as personal. The Man Who Wasn’t There, however, serves beautifully as a stealth riposte to the accusation that they’re merely superficial showmen who don’t put their heart and soul into their work. Ostensibly the tale of a tight-lipped barber (Billy Bob Thornton) who winds up in the electric chair for a crime he didn’t commit (while escaping punishment for a crime he did commit), the film subtly explores the deep feelings that can lurk beneath a passive exterior; its Rosetta Stone is a seemingly irrelevant flashback involving a salesman trying to talk Thornton’s Ed into paving his driveway with tar macadam—a scene even more mysterious, and more significant, than the much-discussed Mike Yanagita scene in Fargo. Ironically, because The Man Who Wasn’t There is a noir-tinged period piece shot in black and white, it was dismissed in some quarters as just more of the Coens’ style-over-substance noodling. In fact, this is as close as they’ve ever come to making a heartfelt personal statement. It’s just not in their nature to do so without a protective layer of genre.

Even with that in place, however, being so open apparently made them nervous. Back in the mid-’90s, after Hudsucker crashed and burned, the Coens took on a number of screenwriter-for-hire gigs, revising others’ scripts and penning updated remakes of some minor British classics. Directing these hadn’t originally been their plan, but now they decided to make Intolerable Cruelty, from a screenplay originally written by Robert Ramsay and Matt Stone. Starring George Clooney as an unscrupulous divorce attorney (whose “Massey Pre-nup” has saved many a man from a golddigger’s clutches) and Catherine Zeta-Jones as an equally formidable impending divorcée, the film has energetic performances and some fun moments, but it never remotely approaches the heights of wholly original Coen work—they just sprinkled some extra cleverness (“You want tact? Call a tactician”) onto what would otherwise have been a forgettable tart rom-com. And it’s still pretty forgettable, frankly, though Cedric The Entertainer, as private eye Gus Petch, does his best to keep things spirited via sheer dogged enthusiasm.

Another gun-for-hire job, The Ladykillers, quickly followed. A remake of the 1955 comedy starring Alec Guinness, it is by any sensible reckoning the least interesting film the Coen brothers have ever directed themselves, distinguished only by Tom Hanks’ aggressively unctuous performance as the leader of a criminal gang passing themselves off as a musical ensemble so they can tunnel through a widow’s cellar into a casino vault. The brothers’ unexpected appetite for lowbrow yuks, mostly unexercised since Crimewave, reappears here, notably in a character played by J.K. Simmons who suffers from irritable bowel syndrome, which the Coens find endlessly hilarious. With an actor less skilled than Hanks in the lead role, The Ladykillers would have been a complete bust. Caressing each syllable with his tongue as he speaks it, he makes such mundane lines as, “We shall require a Hefty bag” play like they were written by Oscar Wilde. But there’s nothing he can do about the film’s quaint ideas regarding elderly black women. When Irma P. Hall has to slap the shit out of someone for cursing, complaining about his “hippity-hop” language, it’s cringing time. (In general, black people don’t figure prominently in the Coens’ work. O Brother, Where Art Thou? is the main exception, with the “Soggy Bottom Boys”—Clooney, Turturro, and Nelson—even claiming to be black while negotiating with Stephen Root’s blind radio-station manager.)

Not much more appetizing is Joel and Ethan’s contribution to Paris, Je T’aime, an omnibus film celebrating the city’s 20 arrondissements (or districts). The Coens’ short, “Tuileries,” is set in the First, where the Tuileries Gardens and the Louvre are located; it stars Steve Buscemi as an American tourist who gets the shit kicked out of him after he inadvertently makes eye contact with a couple making out across the subway platform. With only six minutes at their disposal, the brothers don’t have enough time to do anything but heap indignities and abuse on Buscemi’s clueless schmo; “Tuileries” is an obnoxiously shallow illustration of the basic principle that life is shit, and it ends with Buscemi comparing his painful experience with the mystery and romance promised by the guidebook he’d purchased. This sort of crass nihilism is for lesser mortals—for the duration of the short, it does seem as if they “believe in nussing.”

| 4.0 | No Country For Old Men | 2007 |

| 4.5 | ”World Cinema” (included in To Each His Own Cinema) | 2007 |

| 4.5 | Burn After Reading | 2008 |

| 2.5 | A Serious Man | 2009 |

| 3.5 | True Grit | 2010 |

| 2.0 | Gambit | 2012 |

| 3.0 | Inside Llewyn Davis | 2013 |

What finally broke the Coens’ slump was their collaboration with another great artist. Just why No Country For Old Men was perceived as one of the best movies of the past decade, while 2013’s extremely similar (and equally impressive) The Counselor was treated like toxic waste, isn’t clear; both are excellent visual presentations of Cormac McCarthy’s pitiless sensibility, though No Country admittedly boasts a bit more of a conventional plot, in the sense that there’s a bag full of money everyone’s trying to get their mitts on. In any case, Joel and Ethan seem liberated by encountering a worldview even darker than their own, and their film is, with few exceptions, scrupulously faithful to McCarthy’s novel, even omitting the same major events (of which readers/viewers learn only via the aftermath). Javier Bardem won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor as ruthless hired killer Anton Chigurh, and he’s terrific, but the film deserves credit for relaunching the career of Josh Brolin, who gives poor overconfident Llewellyn Moss an appealingly plainspoken ruggedness, underplaying every scene beautifully.

It’s theoretically possible that Llewellyn Moss appears again in the Coens’ hilarious short “World Cinema,” which was commissioned by the Cannes Film Festival for its 60th anniversary (along with films from more than 30 other major directors from around the globe) and assembled into an omnibus feature called To Each His Own Cinema. Josh Brolin is dressed like Moss, though the action takes place at the Aero theater in Los Angeles, where patrons have to choose on this particular day between the Turkish drama Climates and a revival screening of Renoir’s The Rules Of The Game. “Is there livestock in any of ’em?” the man in the cowboy hat wants to know, after quizzing ticket-taker Grant Heslov about their respective plots. The punchline to this encounter is oddly touching, especially for what it implies about the future of arthouses and maintaining an audience for the challenging movies they show.

Few people saw “World Cinema” at the time, though, so Burn After Reading was perceived as the Coens’ direct followup to No Country, which won them Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay. By comparison, this misanthropic black comedy felt to many like a mildly amusing trifle. It was nominated for zero Oscars, and received somewhat mixed reviews. In truth, it’s more trenchant than its predecessor, in spite of its deliberate exaggeration. The byzantine plot, which is essentially Blood Simple played for laughs, creates a microcosm of oblivious self-interest that stands in for government corruption, which the Coens attribute primarily not to Machiavellian strategy, but to sheer stupidity. Among other treasures, Burn After Reading served as a reminder of how funny Brad Pitt can be when he’s allowed to cut loose—he’s even funny when being shot point-blank in the face, which ain’t easy. And the efforts CIA bigwigs J.K. Simmons and David Rasche make to piece together what happened is both priceless and a testament to Joel and Ethan’s ingenuity, which hadn’t had much of a workout for a while.

What most people wanted, however, was A Serious Man, which is clearly A Serious Film (albeit one with a great deal of dark humor). Set in Minnesota during the mid-1960s, when Joel and Ethan were kids, and populated entirely with Jewish characters, it’s superficially the most personal movie they’ve ever made, and was embraced by many as a long-overdue effort to explore their roots. Thing is, though, the Coens are much more comfortable when they had a literary composite like Barton Fink to hide behind. Striving to be semi-naturalistic, they wind up trying to find real-world analogues for their surreal impulses—the painting of the woman on the beach that Barton stares at gets replaced here by a neighbor who sunbathes nude where protagonist Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) can see her—and their need to give their perplexed hero a never-ending beatdown comes across as weirdly sadistic in this context. By far the movie’s best sequence is the one that leaves the real world behind, as a rabbi tells Larry a long, involved story about an orthodontist who finds Hebrew letters embedded on the back of a patient’s teeth. In general, though, A Serious Man strives a little too hard to make life hell for Larry Gopnik, without the distancing effects that allowed previous Coen brothers films on similar themes to avoid pretentiousness. (The movie’s final shot, in particular, strains for a significance that hasn’t been earned.)

The Coens were suddenly working at a furious pace. In the old days, they made a feature every two to three years; since 2007, they churned out a film a year, with True Grit being their fourth consecutive annual offering. Like The Ladykillers, it was a remake—this time of a famous 1969 Western that earned John Wayne his only Oscar—but unlike The Ladykillers, it wasn’t laborious and tiresome. Jeff Bridges took over Wayne’s role as Rooster Cogburn, and gives good irascibility, but newcomer Hailee Steinfeld carries the picture as vengeful Mattie Ross, a teenage girl who hires Cogburn to apprehend the scoundrels who killed her father in cold blood. Odds are there isn’t a truly great film to be made from Charles Portis’ novel, but the Coens make the yarn as compelling as they can, mining laughs from Matt Damon’s testy performance as Texas Ranger LaBoeuf and suspense from scenes in which Mattie is threatened by various hard men, including Josh Brolin as the scofflaw she seeks. It’s a better movie than the 1969 version, but that doesn’t mean it was the best use of the Coens’ time. Then again, they were moving so quickly that it’s hard to complain about how they allocate their creativity.

The flood was over, however. Three years passed before the next (and most recent) Coen brothers film, during which time another of the scripts they’d written for hire back in the ’90s got the green light. Gambit is yet another remake—Michael Caine and Shirley MacLaine starred in the 1966 original—and there are traces of Joel and Ethan’s handiwork audible in the dialogue, as when stuffy British art curator Harry Deane (Colin Firth) refers to a “Texan horse person,” then clarifies: “Equestrienne, not a mutant or a mythical creature.” Cameron Diaz plays the equestrienne in question, and the plot involves their mutual attempt to sell a bogus Monet to pompous billionaire windbag Lord Lionel Shabandar (Alan Rickman). But it’s impossible to care much, as all three characters are tiresomely one-dimensional, and the plot (which bears little resemblance to the 1966 version) coasts on misdirection so banal that even the terminally gullible will see through it. The entire cast—especially Stanley Tucci, camping it up as a German art appraiser—seems lost, which means there isn’t even a strong central performance (à la Tom Hanks) to distract from the nonsense and the fart jokes. (Fart jokes? Really?) Michael Hoffman directed, and proves again, as he did with 1991’s Soapdish, that broad comedy isn’t his forte. Hard to blame the Coens for this, though—no doubt they were as dismayed as anyone to see that the movie actually got made.

Which brings us to Inside Llewyn Davis, which arrived in theaters only 15 weeks ago. This one turned out to be too chilly to land a Best Picture nomination, but its reviews were as sensational as any the Coens have ever received, and the National Society Of Film Critics named it 2013’s best film. (It placed third on The Dissolve’s year-end list, behind only Her and 12 Years A Slave.) All the same, it falls into two of the brothers’ troubling categories, previously mentioned: 1) the half-assed narrative that starts out strong and then drifts into random abjection, and 2) a protagonist who exists solely to be buffeted about by life’s many frustrations, even if many or even most of these are of his own making. The first half of Llewyn Davis is dynamite, but it takes a steep nosedive when Llewyn heads for Chicago, trapped in a car with Goodman’s abusive junkie jazzman and Garrett Hedlund’s monosyllabic pretty boy; the nadir arrives when a cop arrests Hedlund, who has the car keys, without even bothering to see whether he’s stranding any passengers by doing so. Joel and Ethan have always depicted the world as callous and uncaring, but they used to be less didactic about it. Now they devote entire movies to what could be termed “comeuppance overkill.” (Again, Barton Fink fits this mold, but that film’s surrealism makes a dramatic difference.) It’s a distressing trend… but if there’s anything the Coens have proved, it’s that there’s no need to worry that they’re stuck in a permanent rut. What comes next may well be something nobody could possibly expect.

It’ll probably be bleak, though. In an oeuvre of constant change, that’s the one paradoxically reassuring constant.