This week marks the release of Shout! Factory’s handsome Herzog: The Collection set, which brings 16 of Werner Herzog’s films to Blu-ray. They’re just a drop in the bucket—Herzog is a prolific filmmaker who’s been working steadily for more than 45 years, regularly alternating between narrative features and documentaries, and sometimes putting out two or three movies in a single year. But together, the films collected in this set provide a fine overview of the broad themes that drive him—particularly his lifelong fascination with exceptional people, those with unconventional or unfamiliar ways of looking at the world. He doesn’t necessarily approve of his subjects, who have come to their particular perspectives through routes ranging from brainwashing to neglect to artistic genius to madness. And he tends to craft their stories—whether fictional, factual, or somewhere in between—to serve his own unconventional obsessions. From heavily shaped documentaries to sharply reshaped history, Herzog’s films bring his dolorous, cynical, yet often awestruck voice to the fore.

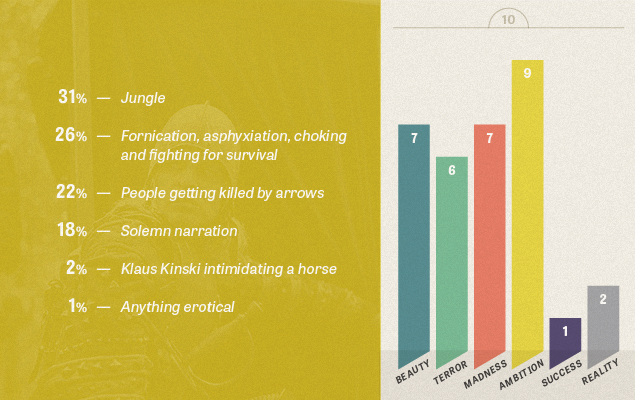

As part of a new occasional feature, By The Numbers, we’ve collectively broken down the Herzog films in this set, ranking them via six categories corresponding to some of the elements most commonly found in Herzog’s work. Rating such different films across the exact same spectrum was difficult, but it highlights how often Herzog’s widely varying works come down to the same basic themes of haunting artistic or natural-world beauty, terrifying situations, insane quests or goals or figures, ambitious schemes or storytelling, plots that don’t succeed in the end, and stories that fall into strange places on the pure-fact-to-pure-fiction scale. But to acknowledge how different all these films are, we’ve also broken them down into percentages based on some of their more distinctive, individualistic elements. Let’s see what the numbers say.

artwork by Joy Burke and Vanessa Lilak

Herzog’s 157-minute epic Fitzcarraldo is his quintessential film. It hits all his favorite themes, including madness, ambition, quixotic quests, lost causes, stubborn determination beyond all logical argument, and the natural world’s beauty and pitiless, impersonal malice. And the filmmaking reflects all those things as much as the story: It’s a perfect Möbius strip, where the art and the creation of the art communicate the exact same things, feeding into each other. The story follows crazed would-be rubber baron Fitzcarraldo (longtime Herzog partner and muse Klaus Kinski) in an attempt to haul a 300-ton steamship across a mountain and into lucrative, otherwise-inaccessible rubber-tree territory, all so he can finance a lavish opera house to bring music to the Peruvian jungle. Herzog felt the best way to represent the scale of Fitzcarraldo’s endeavor was to actually do it himself; Les Blank’s terrific documentary Burden Of Dreams, shot during the film’s production, documents how life imitated art, as Herzog attempted to actually move a steamship across a mountain with the help of a native tribe, all while portraying his protagonist’s efforts to do just that as hubristic and obsessive beyond comprehension.

For a sprawling, two-and-a-half-hour film focused as much on one man’s fevered mindset as on his actions, Fitzcarraldo is surprisingly intense and immediate. Kinski’s seething performance is crucial, as it is in so many Herzog features. (He famously replaced Jason Robards, who became dangerously ill partway into production of a version that had Mick Jagger cast as his sidekick; apart from a few clips preserved in Burden Of Dreams, all the Robards/Jagger footage was tragically, but purposefully, destroyed.) But this is one of those films where the making-of story is key to its mythos, because of the sense that so little of it is artificial movie magic. It’s like watching Herzog document his own ambition, with only the thinnest gloss of fiction to provide a little shine. The film is extremely loosely based on the story of real-world rubber baron Carlos Fermin Fitzcarrald, who similarly hauled a (much smaller, disassembled) boat overland, but it’s more closely based on Herzog’s personal identity at the time. [TR]

Aguirre, The Wrath Of God opens with one of Herzog’s most stunning images: An endless caravan of Spanish conquistadors and their slaves marching down an enormous, fog-shrouded mountain. For Gonzalo Pizarro (Alejandro Repullés) and his men, it’s quite literally all downhill from here, and as their doomed expedition grows increasingly hopeless, those opening scenes retroactively begin to resemble a descent into hell. After much fruitless trudging through the jungle, Pizarro orders a small search party, led by Don Pedro de Ursúa (Ruy Guerra), to scout ahead for El Dorado. Most of the Spaniards remain naively hopeful; only one senses the impending catastrophe, a hunched man with piercing blue eyes named Don Lope de Aguirre (Kinski). “From here it will be easier!” a soldier boasts after they’ve made their way down to the banks of the Amazon River. “No,” Aguirre replies, “we’re all going to go under.” Aguirre is correct.

Kinski and Herzog’s collaboration, which began with Aguirre, was famous for its hysterical outbursts both in front of and behind the camera. (This was the film where Herzog supposedly directed Kinski at gunpoint, though the director later clarified that he only verbally threatened to shoot Kinski if he tried to leave the set.) But Kinski’s performance in Aguirre is far more nuanced and complex than its reputation. The moments of cold calculation far outweigh the ones of mad raving, and if Kinski was unhappy off-camera, he channeled that rage into his character, who declares himself “the wrath of God” in an audacious, fourth-wall-breaking monologue, with expert precision.

Herzog is sometimes accused of treating his tragic protagonists with contempt, judging or punishing them for daring to follow their dreams. But there’s something deeply sympathetic in his depiction of Aguirre, even amid the character’s deception, manipulation, and insanity. True, his journey ends in disaster, alone aboard a sinking, monkey-infested raft. But there’s some kind of moral victory in the purity of this disaster. Like Herzog himself, Aguirre is an explorer. Even in the face of death, he pushes on, driven by an insatiable desire to discover what lies just beyond the next bend of the river. He loses, but he never admits defeat. [MS]

A lot of Herzog’s work falls under the category of “strange but true,” but with his 1979 remake of F.W. Murnau’s 1922 silent horror classic Nosferatu (itself an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula), Herzog plunged deep into the supernatural, telling a story about a mythical monster. Kinski—inevitably—plays Count Dracula, a feared aristocrat with ashy pale skin and the teeth, fingernails, and eyes of a rodent. When Dracula entertains real-estate agent Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz), he becomes obsessed with a picture of Jonathan’s wife Lucy (Isabelle Adjani), and travels to the Harkers’ home city of Wismar, spreading death and derangement everywhere he goes.

Herzog honors Murnau’s original vision throughout Nosferatu The Vampyre, from the beastly visage of Kinski’s Count Dracula to the way that so much of the action plays out in near-silence (aside from the faintly proggy Popol Vuh score). And yet there’s no mistaking this Nosferatu as a Herzog film—and not just because of the presence of Kinski, who brings more fragility and pained human desire than malice to the title character. When Jonathan Harker is walking to what looks like the end of the Earth to reach Dracula’s estate, or when characters’ letters and journals are being read aloud in voice-over, or when Lucy and Dracula have contentious conversations about the nature of existence, Nosferatu could just as easily be one of Herzog’s essay-documentaries, combining stunningly beautiful footage of a forbidding wilderness with earnest rumination on humanity and nature.

The philosophical bent of Herzog’s Nosferatu establishes a kind of intellectual reserve that keeps the film from being viscerally scary. But it is creepy as hell. There’s a weary fatalism to Adjani’s performance as Lucy Harker, which Herzog matches visually by showing Wismar being overrun by large white rats that the town’s socialites stubbornly ignore. Herzog is fascinated by the disturbing physical presence of these rat hordes, and by how weird an actual bat looks when it’s flapping around in Lucy’s bedchamber and climbing her curtains. There’s a strong sense throughout Nosferatu of the darkness and pestilence that runs under everything, which is evident even in Jonathan Harker’s triumphant march through the Borgo Pass to Dracula’s castle. His journey is stirring, right up to the moment when the door opens, Dracula emerges, and the Harkers’ lives are effectively over. [NM]

Herzog based this fictional drama around a real-life mystery, but stripped away much of its mysteriousness in the process. In 1820s Nuremberg, Germany, a teenage boy who wrote his name as Kaspar Hauser appeared at the home of a cavalryman with a letter claiming his father was a cavalryman and he wanted to be one too; the boy appeared to have a limited vocabulary and possibly a limited intellect, and eventually expressed that he’d been raised in a tiny, darkened room with no access to the outside world, or people other than his jailer. Herzog portrays much of this faithfully, but he cast 41-year-old Bruno Schleinstein as Hauser, which implies a significantly larger sense of sadistic commitment from his captor. The real-world case was plagued by inconsistencies that led some to consider Hauser a liar and opportunist, but Herzog plays out his version of events as literal and entirely accurate, including his strange death.

For a film so accurate in some regards (like the exact wording of Hauser’s letter to the cavalryman and a letter his murderer supposedly left with him), The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser feels crafty and artful in other areas, like in Hauser’s stiff, awkward interactions with children and the gawkers who come to see him, and in the way, as he’s polished by generous and curious caretakers, he comes to resemble a well-dressed, man-sized doll accepting whatever pose he’s given. And yet he sometimes outsmarts the people around him, either through obduracy or native cunning. Schleinstein is a preposterously ugly man in a preposterously ugly world of grim stone buildings and simpering aristocrats, but Herzog focuses on how in spite of his miserable history and current limitations, he comes to love life, and resent being forced to leave it. [TR]

Less than a week after finishing Nosferatu The Vampyre, Herzog’s cast and crew started work on 1979’s Woyzeck, an adaptation of Georg Büchner’s play about a poor soldier (played here by Kinski) who allows himself to be abused by his superiors, so that he can make money for the common-law wife (Eva Mattes) who despises him. With minimal time to plan, Herzog employed a simple visual style for Woyzeck, with very few camera moves or cuts; and as a result he completed the entire film in less than a month (after 18 days of shooting and four days of editing). That leanness can make Woyzeck seem at times more like a doodle than a fully realized film, though the approach mostly suits Büchner’s text, which was itself unfinished. What Büchner left behind are raw, intimate scenes of confrontation and psychological torment, which Herzog renders with apt immediacy.

In keeping with Herzog’s career-long concern with “realness,” Kinski’s performance in Woyzeck is one of the actor’s most powerfully vulnerable, reportedly informed by Kinski’s actual physical exhaustion after Nosferatu. The soldier Woyzeck isn’t a strong man. He’s been broken by his cheating wife, and by the very Herzog-like army doctor who forces him into cruel experiments. Woyzeck is bookended by two of the rare moments in the film when Herzog deploys a cinematic effect. In the first, as Woyzeck goes through military drills, Herzog speeds up the film, making the hero look like a cartoon character. In the second, as Woyzeck finally snaps and commits a horrific act of violence, Herzog uses slow-motion. There’s a startling transformation that occurs in Woyzeck, from comedy to lyrical horror, all anchored by the frazzled Kinski. [NM]

Written for The Enigma Of Kasper Hauser star Bruno Schleinstein (a.k.a. Bruno S.), Stroszek draws on elements of Schleinstein’s life in telling the story of a consummate outsider who emigrates from a bad situation in Berlin only to fall into a different sort of trouble in America. As the film opens, Stroszek (Schleinstein) gets released from prison only to wander into a series of traps. Diminutive, good-natured, hard-drinking, and generally ill-equipped for the world, he makes his living as a street musician and extends a helping hand to Eva (Eva Mattes), a prostitute in the thrall of a pair of violent pimps. Invited to accompany their elderly neighbor Scheitz to America, they take him up on the offer, but even with the promise of jobs and easy credit, they find it hard to make a better life in the Land Of Opportunity.

Stroszek is, in some respects, the opposite of Herzog’s usual dreamers. He doesn’t ask that much from life, but his small yearnings get him in trouble: Eva gets restless, he’s unsafe even in his cluttered Berlin apartment, he desires little from America beyond the ability to keep afloat, then watches that wish float away. It’s one of Herzog’s most fatalistic films. An early, lovely scene finds a friendly doctor showing Stroszek a premature baby and demonstrating the child’s grip reflex as an example of humanity’s innate desire to survive before suggesting the helpless infant is all potential, and might even be the German chancellor some day. But it ends with images of rabbits and chickens dancing and doing tricks in a live-animal arcade, the same survival instincts turning them into slaves for the amusement of others. Sometimes the dreams that keep us going turn us into fools. [KP]

For their final film together, Herzog and Kinski created a thematic bookend to their first pairing, Aguirre, The Wrath Of God. Like Aguirre, Cobra Verde is about an explorer sent against his will on a suicide mission into the unknown. Kinski plays Francisco Manoel da Silva, a Brazilian rancher who becomes a notorious bandit named Cobra Verde. He wanders into a job as an overseer on a sugar plantation, but after he impregnates all three of his boss’ daughters, he’s punished with an even worse assignment: sailing to Africa to restart the slave trade with an uncooperative king. Improbably, da Silva succeeds, at least until he finds himself in the middle of a power struggle over the throne, when the king’s mad cousin recruits him to train his army of female warriors.

Kinski died just four years after Cobra Verde’s release, and he looks like he’d aged several lifetimes in the 15 years since he’d made Aguirre. Still, he musters enough strength to go full Kinski in several memorable sequences, as when he frantically runs through a platoon of African women, belligerently bullying them into learning his fighting techniques. And his exhausted appearance works particularly well during the film’s conclusion, when Brazil abolishes slavery and abandons da Silva to an unhappy fate. (“To our ruin!” he toasts after he receives the news that he’s a marked man.) Kinski's final scene in a Herzog film is a fitting one: Da Silva on a sun-dappled beach, attempting to make a hasty getaway in a giant rowboat. But the ship is too big; no matter how hard Kinski pulls, he can’t drag it into the water. In one long take, Herzog observes Kinski straining and straining, until he eventually collapses into the surf. It’s a beautiful coda to one of the greatest and most tumultuous cinematic partnerships in history, and a perfect echo of the end of Aguirre: One man alone with nothing but his boat, the sea, and his defiance in the face of overwhelming futility. [MS]

Herzog’s fascinating, boldly confessional 1999 documentary about his relationship with Kinski suggests a new test for determining the intensity and ferocity of difficult working relationships: Do the parties at any point nurse serious plans to murder each other? Sure, lots of people get angry enough with co-workers that they experience what feels like a murderous rage, but according to My Best Fiend, Kinski and Herzog went many steps further, and actually hatched plans to kill each other following one grievous offense too many. They weren’t alone, either: In another highlight, Herzog confesses that during the filming of Fitzcarraldo, the tribespeople who were serving as extras volunteered to murder Kinski on Herzog’s behalf, but he talked them down because he still needed Kinski to finish the movie.

Watching My Best Fiend, it’s easy to see why Kinski’s craziness might drive a man to homicidal fantasies. His ghoulish features animated by some dark, demonic energy, Kinski (who was already dead by the time Herzog stitched the film together) rages through scenes from the six movies he made with Herzog, plus behind-the-scenes footage that’s as electric and compelling as anything that made it into their films. But while Herzog and Kinski’s relationship was defined by violent conflict and seething resentment, it was also full of unexpected warmth, tenderness, and humanity, as these two strange, complicated, borderline impossible men came to understand how much each party brought to their collaborations. My Best Fiend is ultimately a touching and lovely elegy for a friend, but this is Herzog, so it’s full of fury and dark emotions almost too combustible to be contained by any screen. [NR]

Dieter Dengler, the protagonist of Herzog’s 1997 television documentary Little Dieter Needs To Fly, has experienced traumas that would destroy lesser men. He grew up in war-torn Germany, endured a Dickensian apprenticeship with a blacksmith, was shot down and subjected to endless torture by the Viet Cong, then re-experienced trials of the damned while trying to escape barefoot through the thick, man-killing jungle.

Yet the aviation-obsessed Dengler who guides Herzog through his back pages in Little Dieter—traveling to Vietnam, Germany, and his current home in the United States as he recounts his too-strange-for-fiction adventures—is incongruously pleasant, even upbeat, as he recounts the almost unimaginable torment he endured during wartime. Dengler speaks matter-of-factly about the most agonizing forms of torture, and in his remarkable ability to transcend the horrific injuries that have been committed against his body and soul, Herzog finds a man who personifies the resilience of the human spirit. Herzog obviously saw much of himself in Dengler, and was so inspired by his heroism that he made a second film about his experiences in the underrated adventure movie Rescue Dawn. In the 2007 narrative feature, Christian Bale plays Dengler and Steve Zahn delivers a heartbreaking performance as Duane Martin, the best friend whose death is one of the most heart-stopping moments not just in Little Dieter Needs To Fly, but in Herzog’s entire filmography. [NR]

After a two or three-day hike into the Nicaraguan jungle, Herzog and his crew reach a village populated by Miskitos, an indigenous people in revolt against the ruling Sandinistas, who are razing and pillaging their homes and killing vast numbers of them. Beckoned to come to the area by his friend, the journalist Denis Reichle (who gets a co-director credit), Herzog uses the Miskito rebels as a devastating case study in the deployment of child soldiers around the world. It’s impossible for boys as young as 10 to be motivated by ideology, or even to understand why they’re fighting; when asked, they often recall members of their family who have been killed or say that their mothers ordered them to the front lines. The tragic irony of child soldiers is that this very lack of understanding is what makes them effective, unquestioning troops, often more courageous in battle than their adult comrades.

Peppering his omnipresent voiceover with observation and translation, Herzog attempts first to understand the context for the Miskito rebellion, listening to horror stories about a defenseless people subjected to the murderous whims of Sandinista troops. (And the historic exploitation and persecution of the Miskitos is certainly not limited to the Sandinistas, either.) But the second half of this 45-minute television documentary shifts focus to the underage recruits as they go through their five-week training regimen in preparation for war. Reichle, who recalls fighting off the Russians as a 14-year-old with the Volkssturm, asserts himself as the film’s moral voice, pointing out how easily a child can be brainwashed into waging wars he might question as an adult. The context for using child soldiers ultimately doesn’t move him. And Herzog makes that the exclamation point. [ST]

Early in his career, Herzog accepted some more straightforward documentary assignments, but then would take advantage of the circumstances to pursue his own interests. While Herzog was in Africa making The Flying Doctors Of East Africa, he started filming what would become Fata Morgana; and after shooting a film about the disabled called Handicapped Future, Herzog stuck around a while to spend more time with a woman in her 50s named Fini Straubinger, deaf and blind since childhood. Able to speak articulately and to communicate with other deaf/blind individuals through taps and strokes on their palms, Straubinger would serve as Herzog’s guide through the lives of people who can’t see or hear for the 1971 film Land Of Silence And Darkness

There are moments in Land Of Silence Of And Darkness that do seem more like a traditional advocacy doc, with Herzog wondering why the German people don’t do more to make life more pleasurable for his subjects, all of whom are capable of finding joy in the unlikeliest sensations. (One younger man continually bangs an inflated ball against his face; another older man spends minutes on end literally hugging a tree.) But more often, Land Of Silence And Darkness just watches with quiet wonder. It’s the first in what would become a lengthy series of Herzog documentaries that show viewers the harsher extremes of life on Earth, asking probing, personal questions about what it’s like to live so far removed from the comforts and routine of most moviegoers’ experience. [NM]

One of the most inscrutable of Herzog’s essay-documentaries, 1992’s Lessons Of Darkness was shot in and around Kuwait in the immediate aftermath of the Gulf War, focusing primarily on the oil fires set by the Iraqi military during its retreat. Herzog works in a few interviews with locals who’ve had their lives disrupted by the war, and he provides occasional voiceover narration—though in general, all the comments in Lessons Of Darkness are vague, and not specifically applicable to the fighting or the fires. Instead, Herzog seems fascinated by how this good-sized plot of the planet Earth has been transformed into a charred, alien landscape, mostly populated by emergency crews in protective gear.

According to the box set’s liner notes, Herzog was booed at the Berlin film festival after a screening of Lessons Of Darkness, and accused by the audience of being more interested in pretty pictures and philosophizing than in the human toll of the Gulf War. That’s not an entirely unfair criticism. Throughout his career, Herzog has shown less engagement with any one particular political conflict or social issue than with the bigger picture of how humans continue to fight with each other and with their environment. But then that’s why Lessons Of Darkness is still so beguiling, decades after the war that inspired it. It’s a vision from another world, shot on this one. [NM]

One of Herzog’s most experimental efforts, Fata Morgana mixes footage filmed throughout Africa—from Algeria to the Sahara to the Ivory Coast—with a poetic voiceover, some of it taken from the Mayan creation myth as recounted in the Popol Vuh. If that sounds like a hodgepodge of disparate elements thrown together to make a movie, well, it often plays that way, too. But even if it never quite comes together as a film, the best stretches of Fata Morgana have a hypnotic power, and it anticipates both the films of Godfrey Reggio (Koyaanisqatsi, etc.) and Herzog’s recent philosophical documentaries. The images range from the beautiful to the strange to the repulsive, yet here even the animal corpses have a weird sort of beauty. Herzog lingers on them, refusing to look away, forcing viewers to consider an unpleasant aspect of existence and how it fits into the way the world works. It’s a quintessential Herzogian gesture, and there’s something perfectly Herzogian about the way Fata Morgana combines images of Africa, Western music, and Mesoamerican mythology to arrive at a vision of the world that’s unmistakably the product of one Bavarian filmmaker. [KP]

In a career loaded with audacious cinematic stunts, Herzog’s Heart Of Glass offered this doozy: In telling the story of an 18th-century Bavarian village that loses the secret to its glass-blowing industry, Herzog had his actors perform under hypnosis. The effect turns the townspeople into conformist zombies, bereft of purpose and consigned to shuffling off this mortal coil without ever giving a thought to the pointlessness of their endeavors. As a side effect, hypnosis not only liberates non-professional performers from showing their acting range, but allows Herzog to dispense with conventional drama altogether. Town leaders may be desperate to know the formula to the “ruby glass” that was buried with its inventor, but there’s never any doubt that their way of life—and their lives period—are doomed to obsolescence.

There are passages of immense beauty in Heart Of Glass, especially when Herzog sets filtered nature shots to guitar noodling of his frequent collaborators in Popol Vuh, and the hypnosis inspires scenes that are more like horror tableaux than traditional mise en scène. But the sheer inevitability of the town’s demise, combined with the deliberately somnambulant performances, completely robs Heart Of Glass of any drama, and the tedium seeps in like water through a cracked ruby vase. It’s a Herzog film without dreamers, which heightens the despair and strengthens its metaphor about humans betrayed by industry, but makes the actual action of the film inert and impenetrable. [ST]

Inspired by Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd, a 1971 case that weighed the land rights granted to an Australian mining company against those of Aborigines, Where The Green Ants Dream mixes fact and fiction as liberally as it joins absurdist comedy to cultural commentary. Looking every bit the comic foil with his gawky frame and tortoise-shell glasses, Bruce Spence stars as Lance Hackett, a geologist hired by a mining company to test the subsoil of a desert territory for lucrative deposits of uranium ore. But the explosives required to do it rile the local Aborigines, who believe it will disturb the green ants dreaming below, which will have grave effects on humanity. The company tries to appease the natives with a cash settlement and modern advances as small as a digital watch and as large as a cargo plane, but the case winds up before the Australian Supreme Court, which has to determine whether the Aborigines can lay claim to territory outside its designated tribal areas. Hackett works for the company, but he earnestly tries to forge a compromise between the two parties.

There’s no question where Herzog’s sympathies lie in this case, but Where The Green Ants Dream isn’t entirely the broad condemnation of colonization and industry it seems to be. He’s more interested in the folly of two cultures that cannot remotely comprehend each other, and fail in even the smallest attempts to bridge the communication gap. Herzog’s gifts for comedy are limited, and the courtroom sequences are beyond discreditable, but he finds inspiration in Aborigines’ dogged refusal to abandon their traditions and principles in the interest of self-preservation. In one scene, a group of natives is shown sitting in a circle in a grocery aisle, and it’s explained to Hackett that a sacred tree was hacked down in that spot to make room for the store. The world may change absurdly around them, but they aren’t going anywhere. [TR]

In just his second feature, Herzog produced one of his most singular and provocative works, a virtually plotless orgy of anarchy and destruction that plays like a cross between Tod Browning’s Freaks, Luis Buñuel’s Land Without Bread, and Jean Vigo’s Zero For Conduct. The action begins in medias res as a group of dwarfs are rebelling against the institution that houses them. No reasons are given (though they can be imagined), no goals are apparent, and no dramatic structure or narrative arc is foisted on the proceedings. Herzog offers a villain of sorts in the institute’s director, who tries to gain leverage by holding another resident hostage, but the threat is so empty that the hostage laughs his way through the whole ordeal and the director gets pelted with projectiles whenever he makes an appearance.

Discarding all cultural sensitivities around the depiction of little people, Even Dwarfs Started Small seems at first glance like an act of carnival exploitation, and grotesqueries abound, from cockfighting to the pranking of blind dwarves to a scene where one especially diminutive man futilely attempts to foist himself onto a marital bed. But Herzog feels like the dwarfs’ invisible collaborator, joining them in a sustained demonstration of civilization descending into chaos and madness—a theme that he’d repeat again and again in subsequent films. Shooting in stark black and white on a remote outpost on the Canary Islands, Herzog presents the institution as society in miniature, and bears witness to its relentless, nightmarish dismantling. Always one for visual metaphor, he settles on the image of a driverless truck spinning in circles, with no purpose and no destination; it will run out of gas someday, after wasting a tank going nowhere. [ST]