Style/Storytelling

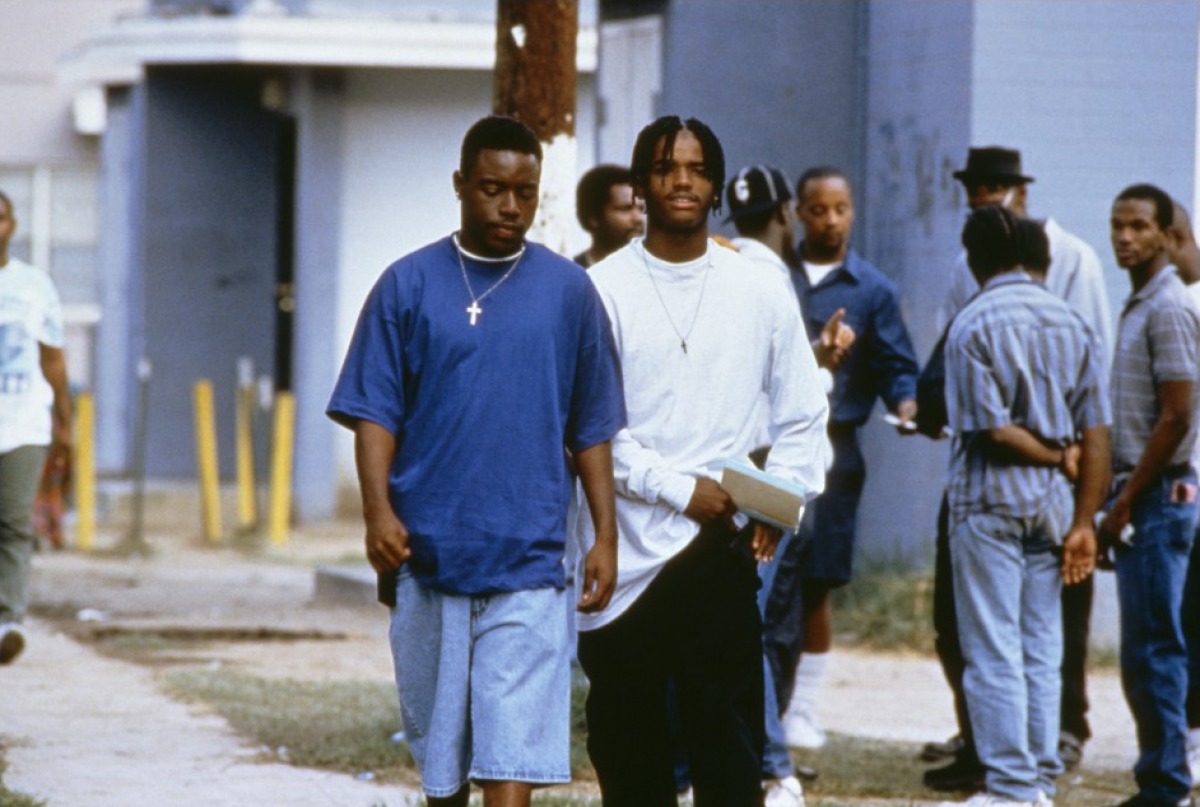

Scott: My reaction to seeing Menace II Society in theaters was absolute astonishment—it was so stylish, so uncompromising, so relentlessly despairing in its depiction of hood life, and I’d never seen anything like it. Seeing it again today, for the first time since 1993, I recognize that I had seen something like it—Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas—and the film is rougher around the edges than it seemed at the time. The Scorsese-style voiceover narration could stand to be more vivid, but it does a fine enough job of establishing this milieu as a place of constant violence and retribution, from which no one can find quarter. Though the Hughes brothers are following Caine as he’s trying to avoid his parents’ tragic legacy, they take an almost episodic approach to storytelling, treating the film as a slice of life as much as a straight-ahead crime-and-redemption story. The impression left most deeply for me is the rage and conflict present in virtually every scene. It’s inescapable, the basic tenor of everyday life.

Tasha: Even with the introductory narration explaining how Caine was basically born into a society of gangsters, I still didn’t clue into the Scorsese-ness until the sequence where Caine travels through a party with a camera at his back, and comes out on the other side among his peers, whom he introduces in a flurry of names and brief distinguishing characteristics. That follow-shot and the here-are-the-players sequence are such Scorsese signature—seen Goodfellas, Casino, and The Wolf Of Wall Street, just for starters—that it feels like a cliché when Scorsese does it now. Here, it just feels borrowed, though it is an efficient way to set up the rest of the story. With Scorsese, most of the people introduced in those early-movie blitzkriegs turn out not to matter much; they’re around for the same reason as the “Look at all my stuff!” montage at the beginning of Wolf Of Wall Street, with a protagonist establishing the wallpaper of his daily life. In Menace II Society, some of the people Caine introduces are never developed—because they’re killed before viewers can get to know them. He’s just differentiating between his friends enough that the movie can feel a sense of inevitable, terrible progression as they die off one by one.

Nathan: Part of what makes the long tracking shot of the party so effective is that it establishes that even though violence and death exist all around these characters, they’re committed to enjoying themselves. Circumstances might have forced them to grow up quick, but they’re still fundamentally kids. Their lives are not a joyless trudge to the grave; they also have sunshine, barbecues, pretty girls, and a world of easy pleasures. That’s part of what makes the lifestyle so seductive, and why it sucks Caine in. Within the course of a single elaborate tracking shot (or a series, as there are a number in the early going), the Hughes brothers map out an entire world, introduce its players, and lay the foundation for the ugliness that will follow.

Noel: I think your point about the sense of camaraderie in the community is key. It’s what lends a tragic dimension to all the violence. Between the scenes where they’re gunning down their rivals, these young men are enjoying themselves, and showing real compassion for each other. That’s also why Menace II Society provokes such complicated reactions, as we’ll get into more later when we talk about the film’s morality. It’s hard to make sense of what the Hughes brothers want us to think from moment to moment. Honestly, I’m not sure if Menace II Society’s inconsistent tone is a bold choice on the Hughes brothers’ part—pushing the audience to care about conscience-less murderers—or just the result of their immaturity as storytellers. But that wild-card aspect definitely makes the movie more exciting and provocative than some feature-length public-service announcement would’ve been.

Keith: The Hughes brothers found a great collaborator in director of photography Lisa Rinzler, who went on to shoot their even more stylish follow-up, Dead Presidents. This was Rinzler’s second major feature after Tamra Davis’ Guncrazy remake, and it impressed me enough that I remembered her name for years afterward. (There aren’t that many female cinematographers out there, which helped it stand out.) Part of what makes Menace II Society work is the way the film uses moody interiors and ominous lighting to set the tone, but without those touches seeming stylized beyond believability. Yet some of the most memorable scenes, like the finale, don’t goose the atmosphere at all, which is effective in its own way. The film’s world is one in which horrible things happen under the warm glow of the California sun.

Tasha: Keith, I’m going to split hairs at you a bit: Maybe you’re right and the interior lighting doesn’t seem overly stylized, but it certainly seems extremely stylized, in a way I found interesting in part because it jazzes up some extremely cheap-looking sets. Interior spaces like Caine’s childhood home, with its bloody red lighting and smoke, don’t even look like homes so much as undecorated stage sets where the camera stays close to the characters because there’s so little else to see. I find a couple of things fascinating about that: First, the resourcefulness of working around a small budget, and second, the way it conveys how graceless and simple life gets for a couple whose lives basically revolve around drugs, cash, and violence. The sets look stagey and fake in part because there’s no decor, but that’s the way their apartment or home would look—no one has spare money for, or interest in, unnecessary furniture or wall art.

Social Commentary

Keith: For about half its running time, it doesn’t seem like Menace II Society is going to offer much direct social commentary. The opening scene finds O-Dog committing cold-blooded murder while Caine looks on… and these are the protagonists. Afterwards, we get a lot of matter-of-fact scenes of life in Watts. The Hughes brothers don’t exactly glorify it, but they’ve taken from Scorsese what a lot of Scorsese-inspired directors miss: the ability to make vice look thrilling and awful at the same time. The moralizing kicks in around the time Charles S. Dutton shows up, and even he advises them to “survive” above all. But it’s more effective than it would be in a preachier film, because Menace keeps adding crushing details to its depiction of Watts life. It never justifies its characters’ behavior, but it shows what it’s a response to. That’s its own form of social commentary, particularly in 1993, when a lot of moviegoers had never seen these neighborhoods depicted on film. Just being there is significant.

Tasha: Caine’s early statement that his seeming best friend, O-Dog, is “America’s nightmare: young, black, and didn’t give a fuck” is a rare moment of larger perspective, where he sees past his own situation, and into how the rest of the world might see him and his friends. He’s obviously telling this whole story so viewers will understand his perspective and his life, but just as he’s horrified when O-Dog murders the convenience-store owners in the opening—seemingly when Caine is still young enough to see the world from outside the violence he’s been steeped in his whole life—he has enough self-awareness in describing his friend to admit that O-Dog doesn’t just look like a threat to middle-class white America, he actually is one. It’s telling that in spite of that accurate summation, and in spite of his proof that O-Dog is perfectly willing to kill people casually, on impulse, without thought of consequence, they’re still buddies. That’s its own form of social commentary, though I do wish the film had touched a little on what binds the two of them besides proximity.

Nathan: I would argue that Menace II Society foregrounds social commentary a lot earlier, in the extended sequence devoted to the Watts riot at the beginning. Menace II Society doesn’t just show a flash of the riots or reference them, it lingers on them, particularly that haunting helicopter shot of Watts looking like a war zone rather than a neighborhood in the United States. Narratively speaking, the Watts riots have little to do with the events of Menace II Society, but the film explicitly posits them as the moment when drugs came to dominate the neighborhood, bringing with them an epidemic of gangs and violence. That helicopter shot of Watts in 1965 during the riots has a bookend when, after the opening shooting and the flashbacks, we’re reintroduced to Watts, circa 1993, by another helicopter shot that presents the neighborhood as one constantly under surveillance, with the police as an occupying force the inhabitants will never make peace with.

Tasha: I also think there’s an inherent understanding that the Watts riots were a watershed moment both in the civil-rights story and in mainstream America’s attempts to understand black-on-black violence: The commentary of the time was often focused on bafflement that the rioters were reacting with anger to white police oppression by burning, looting, and destroying their own neighborhood. Locally directed violence is still the norm in the present of Menace II Society, to such an extent that Caine repeatedly shrugs off the chance to move away with his love interest Ronnie and her son. The degree to which the crime, theft, and murder is all turned inward, on Watts, doesn’t change from the 1960s clips to the 1980s story.

Noel: It’s not just the direct violence that’s destroying the community; Menace II Society is blunt about how the macho culture of these young men is making escape from the cycle of murder/revenge-for-murder/revenge-for-revenge-for-murder all but impossible. Raise a voice in protest, get called a “bitch.” Agree that you’re “down with a 187,” get praised by your peers for being a cool, right-thinking guy. The choices are pretty limited.

Tasha: True. O-Dog’s first onscreen murder, Caine’s father gunning down his friend at the card table, Caine’s own first killing—they all happen because no one wants to lose face, either by letting an insult slide or by backing down from a confrontation or a perceived obligation to the dead. There’s an awful lot of masculine fronting in this movie, as people dutifully escalate fights or even shoot people they don’t really want to shoot, because their culture makes them feel like it’s necessary to never show hesitancy. Caine even takes shit from O-Dog for being upset when Caine was bleeding to death in the hospital. They’re both whistling past the graveyard when they mock each other over getting emotional when Caine was shot, but they’re also reconfirming social norms by chiding each other for being afraid—and trying to mask their own fear by accusing each other of showing even more fear.

Scott: In terms of social commentary, it’s useful to think about Menace II Society as an answer to the explicit moralizing in Boyz N The Hood, which had Laurence Fishburne’s Furious Styles holding court about the gun and liquor shops on every corner, familial responsibility (“Any fool with a dick can make a baby, but only a real man can raise his children”), and brothers killing brothers. The Charles S. Dutton character is the closest to a Fishburne analog we get in Menace II Society, and it seems like we agree the movie would do better without him. For the most part, the Hughes shoot for a heightened nihilism that’s rooted in the Watts powder-keg, but otherwise doesn’t need much in the way of additional commentary.

Nathan: There’s also an interesting meta element to Dutton’s appearance, in that the actor himself is famously an ex-convict who was able to turn his life around and become a successful television and movie actor. So part of the power of that scene, which we all agree is way too on-the-nose, lies in the audience knowing Dutton’s history. I also found it notable that the cop who so hypnotically tells the protagonist that he’s fucked up is played by Bill Duke, a ubiquitous character actor who also directed, among other films, Deep Cover, a neo-noir thriller that, if anything, is even bleaker than Menace II Society in its take on the ugliness of contemporary society and race relations.

The Hood Movie

Tasha: Menace II Society takes a different tack from other movies about life in violence-plagued, gang-controlled, predominately black urban ghettos. Specifically, it’s straightforward and blunt about its characters’ criminal behavior and general lack of regret; they’re trapped in a bad place with bad role models, but Caine still consciously decides to go from cringing at O-Dog’s behavior to joining in, and from regretting his family history, and how he was raised, to giving Ronnie’s son the exact same experience, practically line for line and note for note. Menace II Society sympathizes with its characters, but it’s tuned to disapprove of their decisions, and present them as decisions, rather than the inevitable consequences of growing up in the hood. John Singleton’s earlier hit Boyz N The Hood, similarly underlines choice and decision-making, but it’s more soulful and sad about the limited options they have, and it lets a few characters navigate gang culture and escape to a bright future. Even earlier, the jittery, bright, wholly sympathetic Do The Right Thing emphasizes neighborhood tensions, but only shows them turning deadly because of the thoughtless intervention of white policemen. Then after Menace II Society came films like New Jack City, which glorified the gangsta lifestyle, and then more films that overtly sympathized with people trapped in the hood, like Hustle & Flow. Menace II Society seems singular to me in its specific take on urban life, even though it explores some themes that crop up in all these movies. How does it particularly stand out from the pack for you?

Noel: As I recall, when Menace II Society came out in 1993, it was touted as harder and “realer” than Boyz N The Hood and Do The Right Thing, which I’d say is true, to a degree. I wouldn’t say it makes the movie inherently better, but Menace does deserve credit for plunging right into the heart of criminality rather than stepping back. Like its predecessors, though, Menace II Society also has a big-picture quality that works against it. Since the world of these movies had been so rarely represented onscreen up to that point—or at least not since the 1970s—filmmakers like John Singleton and the Hughes brothers seemed obliged to make a grand statement. I like Menace II Society a lot, but I prefer some of the movies that came out after the Ultimate Hood Movies had been made, such as Boaz Yakin’s Fresh, and Nick Gomez’s New Jersey Drive. Those films still deal with crime and poverty, but are less laden with social importance.

Nathan: Rewatching Menace II Society, I was surprised at how didactic and, to borrow Noel’s phrase, laden with social importance it was. I remembered it as much more of a straight-up neo-noir with elements of social commentary, and less of a Treatise On The State Of The Black Man In The United States. I think its reputation for being the more hard-edged yin to Boyz N The Hood’s yang is attributable largely to the overt preachiness of Boyz N The Hood, a film remembered these days as much for its straight-up sermonizing as anything else. Part of what sets Menace II Society apart is that it’s not about a fundamentally innocent kid caught between the seductive allure of street life and going straight, like Boyz N The Hood or Juice. It’s about a fundamentally corrupt kid who already sells drugs, who is torn between going so deep into the street life that he can never get out and escaping as the only means of survival. Menace II Society presents its protagonist with, if anything, too many options to escape his destiny (it seems like every 20 minutes, someone offers Caine what appears to be a permanent way out), but the film’s gloomy fatalism suggests he’s stuck in a spiderweb he will never be able to extricate himself from, built by social factors that existed well before he was born.

Scott: The film’s references to gangster movies like Goodfellas had me wondering what Menace II Society’s relationship is to the world it’s depicting. Goodfellas certainly has its genre embellishments, too, but Scorsese was working from an autobiography by Henry Hill, and Hill himself attested to the verity of the film, for whatever that’s worth. (He even claimed that Joe Pesci’s character was toned down from the real guy.) But the cribbing from other films—O-Dog is essentially cut from the same sociopathic cloth as Pesci—has me thinking of Menace II Society as more hyper-real than an attempt to capture the hood as it really was at the time. No doubt the violence, poverty, anger, and hopelessness that pervades the film reflects the reality of growing up in a place like that, but the tone is ecstatic and pulpy, which makes watching a productively uneasy experience.

Keith: But maybe that’s just a case of overstatement being used to make a point. I do understand where you’re coming from, though. You can walk away from a film like Menace II Society and think of Watts as a place of nonstop violence. But what makes neighborhoods like this tragic is that they’re places where many people try to live peacefully, but can’t because of the constant threat of violence. Violence doesn’t happen every day, but it’s an everyday reality that destabilizes life for everyone who lives there. Menace II Society doesn’t linger much on the quiet times because it’s not that sort of movie, but if you take it as documentary, you can get a skewed sense of the problem.

Morality

Noel: The Hughes brothers surely don’t mean for Menace II Society’s audience to approve of Caine’s overall descent into crime, but there are moments throughout the film where murder and theft are treated as… maybe okay? Or at least as something the audience can laugh at without being made to feel bad about it. When O-Dog shoots a crackhead and then offers his crew the junkie’s leftover hamburger, or when Caine steals the hubcaps from “some fool,” those scenes are played for laughs more than for shock. I’m reminded again of Martin Scorsese, who in movies like Mean Streets, Goodfellas, and The Wolf Of Wall Street has shown his protagonists behaving absolutely appallingly, without openly judging them for it. Scorsese got pilloried for that in some circles after Wolf; do the Hughes brothers deserve any tsk-tsking for failing to moralize at every turn?

Tasha: I tend to think they are moralizing, by showing how Caine willingly moves from victim of a criminal upbringing to casual criminality himself. Plenty of hood films show crime, or drug dealing, or murder as an inevitability—the only way to survive a horrible situation, or to earn self-respect in a society that’s largely discarded its black neighborhoods. This one starts off with Caine horrified at O-Dog’s casual murder of a store owner who makes an unwise comment about his mother, and traumatized by a carjacking that leaves him wounded and his cousin dead. But by the midpoint of the film, he’s putting someone else through the same terror just to steal his fancy hubcaps. I agree that scene isn’t played for drama and terror, but I don’t think it’s all that funny, either: It’s making a point that Caine does have choices, and he’s deliberately making petty, self-serving ones. The empathy for others he has a child, and even as a young man, has disappeared to the point where he’s willing to threaten a man with murder for getting his hamburger order wrong. To me, that feels like moral judgment, implying that Caine’s fate isn’t an inevitable tragedy, it’s a morality-tale ending where he brings his own fate down on himself.

Nathan: The scene where O-Dog kills the junkie for offering to suck his dick, then tries to ensure that the junkie’s food doesn’t go to waste, paired with the scene where Caine angrily demands a dude’s shiny car rims and a double cheeseburger, reminded me of Larry Clark’s Bully. The dark comedy in both comes from the weirdly specific amorality, and from the gulf between an audience that understands how fucked-up the characters’ behavior is and the obliviousness of the characters themselves. So these sequences serve two purposes: They reflect the almost surreally, comically jaded nature of the film’s characters (who shrug at O-Dog killing a man in broad daylight for saying the wrong thing), and they’re played for comedy in a movie that might otherwise feel oppressively grim and heavy-handed. I think we’re supposed to be both amused and horrified by Caine and O-Dog’s actions; but also, on some level, we’re supposed to recognize our complicity in being entertained by such violence and amorality. The laughter is supposed to stick in our throats a little.

Here’s another question regarding morality. What do you make of all the people who saw the videotape of the killing at the liquor store (it was apparently the party tape of the summer in Watts that year) and never reported it or processed it as anything other than entertainment?

Keith: I think that’s one of the film’s slyest touches: Here are people taking pleasure in video violence and doing nothing to do the right thing—to borrow a phrase—and they’re being watched by an audience that’s judging them for that. Yet many of us who see the movie thrill to the violence and feel awful about the real-world circumstances that lead to it, then continue to go about our lives as none of it touches us. There’s moralizing in that detail—and in the film as a whole—even if it’s not overt.

Tasha: I also think you can trace at least a little of the casual, amused reaction to the videotape back to the scene where Caine and O-Dog razz each other over being upset when Caine was shot and appeared to be about to die. In the same way Caine is horrified at O-Dog for killing the convenience-store owners, but still hangs out with him and eventually even kills with him, it’s possible that some of the people watching that tape aren’t entirely amoral, jaded, and amused by murder—but they’re going along to get along, because do to otherwise means volunteering for abuse and mockery. Being in a room with a gun-waving multiple murderer who thinks his killings are hilarious (and potentially profitable!) fun is a pretty good incentive to laugh along and order up a copy of the videotape—especially given how useful that videotape later proves to someone who isn’t actually down with whatever Caine feels like doing.

Scott: I appreciate the film’s overall lack of moral judgment, given how difficult it is for a young men like Caine to make it through the days, months, and years without being tarnished by the influences around him. Those include his parents, who bequeathed him a legacy of crime and addiction; O-Dog, who’s shown murdering a convenience-store owner and his wife for the crimes of saying something about his mother and looking at him askance, respectively; and the fundamental stigma of being young and black in America, a condition that wouldn’t be relieved by a change in location. We see him make mistakes. We see him do terrible things. But the Hughes allow the audience to understand his actions in relative terms, which I think is morally proper, despite the film’s nihilistic bent.

Final Thoughts

Nathan: Let’s wrap things up by sending out a little love to scenes, characters, and actors we haven’t mentioned yet. I’d like to bring up my love for MC Eiht’s performance as A-Wax, one of a series of demons on Caine’s shoulder urging him to always do the wrong thing. At the time, MC Eiht was a minor West Coast gangsta rapper associated with the Crips, and he brings to the role an unforced magnetism and rugged charisma. He doesn’t try to seem tough, he just is, and his unforced swagger contributes to the air of authenticity.

One of my favorite moments in the film is when Caine and O-Dog are having a screaming match about whether to seek revenge for the drive-by that killed Caine’s cousin, Harold, and A-Wax instantly shuts them both down for being overly emotional. For men as jaded as A-Wax, there is no moral dilemma at play; it’s strictly about revenge, and there’s no need to raise your voice or get emotional just because you’re about to kill somebody with malice and foresight. That kind of brutal unsentimentally gives the film its potent kick.

What actors and scenes stayed with you?

Noel: She’s only in the movie for about a minute, but the pre-NewsRadio Khandi Alexander stands out to me more now than she would’ve the first time I saw the film. Partly it’s that I’ve seen Alexander be great in a variety of roles since then; but also, as Caine’s junkie mother, Alexander quickly helps establish the world that Caine grew up in, where adults were around, but not really there.

Tasha: While we’re talking about the women in the film: Jada Pinkett’s costumes are such an oddity that they really stick with me. I suspect the Hughes were out to establish her as the “good” girl who stays at home looking after her son, rather than a hoochie who shows off her body and is looking for attention. But it’s still odd how she ends up in the most shapeless, anonymous clothes this side of Kevin Smith.

That aside, the single most memorable moment in the film for me comes when Caine’s grandfather sits him and O-Dog down for a stern religious talk about how God put them on earth for better reasons than to kill people, and Caine protests that he’s never killed anyone. And granddad says, casually, “Oh, I doubt that,” then moves on with his lecture, without pause and with no particular horror. He just assumes his teenage grandkid has killed people, because who hasn’t? Maybe it’s meant as just a scolding moment from an out-of-touch old man, an example of how kids like Caine get profiled no matter what they do, but for me, it underlines a feeling that the baseline expectation, even from Caine’s closest family, is that he’s a young black male, so of course he’s out committing murder on the regular. No wonder he eventually does start killing people; in his environment, it’s so expected, it’s basically background noise.

Scott: This is opening a can of worms—perhaps the commenters can mull over the question—but what happened to the Black New Wave? Following Spike Lee’s lead, there was a time in the early 1990s when it seemed like we were going to get a diverse range of visions from young black filmmakers like the Hughes brothers, John Singleton, Matty Rich, Mario Van Peebles, and others, but the movement, if it could be called that, never really panned out. Menace II Society especially hit like a bomb—so grim, violent, and despairing—but it couldn’t be sustained. The chief culprit, to my mind, is Hollywood, which once seemed interested in bankrolling modestly budgeted films that might provoke a response. (Lee’s Jungle Fever, an astonishingly bold film in retrospect, was a Universal Picture.) But once that interest faded, so did the movement. The Hughes have made some striking films within the system since, like From Hell and The Book Of Eli, but returning to the grit of Menace II Society seems impossible now, for them and for anyone else.

Keith: I want to say more improbable than impossible, especially since Boyz N The Hood and this film seemed to come out of nowhere in the early 1990s. But they didn’t, they just explored part of America rarely seen on films before. The problems they found there haven’t gone away. What’s more, both films have lived on well beyond most films of their era, suggesting there’s still an audience for these sorts of stories, and a need for a new generation of filmmakers to tell them.

Nathan Rabin kicked off our Menace II Society discussion yesterday with his Keynote on the film’s brutal fatalism, and tomorrow, Noel Murray will look at its place in the larger tradition of the gangster movie.