Movies derived from Saturday Night Live do not have the best reputation, to put it mildly. They are widely, and often accurately, derided as cynical attempts to spin popular television characters into a medium that neither demands nor welcomes them. They are similarly notorious for attempting to stretch a single joke to feature-length. The worst SNL-derived films invite that view, but it seems unfair when considering the surprising diversity, venerability, and even, yes, quality of the films inspired by the deathless television institution. Sure, some terrible films originated with Saturday Night Live, but so did beloved and influential comedies like The Blues Brothers and Wayne’s World. And once you factor in movies like Office Space, Bob Roberts, and A Mighty Wind, movies many don’t realize have roots in the TV show, the SNL filmography looks even more impressive.

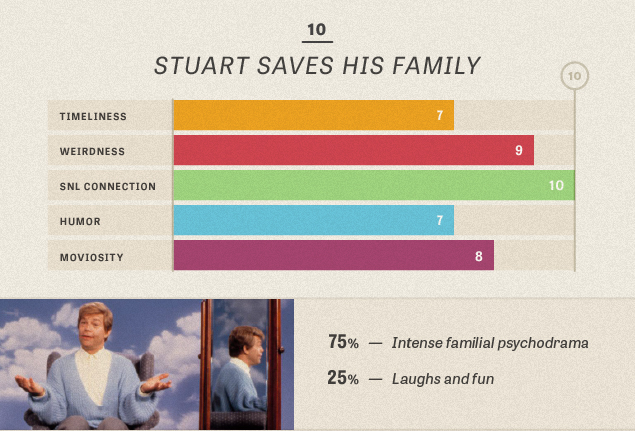

This week’s Movie Of The Week, the hilarious 2010 action-movie spoof MacGruber, illustrates what Saturday Night Live movies are capable of at their weirdest and most inspired. So we took a long trip back through the history of Saturday Night Live-derived films to chart their curious evolution and see where they stacked up in terms of timeliness (How closely does it follow the popularity of the TV character that spawned it?), weirdness (How like MacGruber is it?), SNL connection (How closely tied is it to its SNL inspiration?), humor, and a quality we’re calling “Movieosity,” a measure of its cinematic qualities and whether it holds together as a bona fide motion picture rather than just an exercise in synergy.

Saturday Night Live’s expansion into the cinematic arena got off to an inauspicious start with an anthology film originally planned as a one-off fill-in for SNL, which was later shunted to theaters after it was rejected by NBC censors for its extreme content (at least by the standards of late-1970s broadcast TV). Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video wasn’t ready for prime time or late night. It also wasn’t very good. The project was conceived by SNL’s first head writer, Michael O’Donoghue, as a spoof of the 1962 documentary/exploitation film Mondo Cane, and traded on O’Donoghue’s onscreen SNL persona as “Mr. Mike,” a sardonic misanthrope who would pop up occasionally during the show’s 1970s heyday to tell twisted versions of fairy tales to children or impersonate Elvis Presley with steel needles in his eyes. As Mondo Video begins, Mr. Mike sits cross-legged on the floor of a dingy New York apartment, brandishing a handgun while surrounded by dozens of rabbits. Looking directly into the camera from behind sunglasses, O’Donoghue invites viewers to join him on “an odyssey of aggressive weirdness.” If nothing else, he is true to his word, as Mr. Mike mixes high-concept comedy sketches, parodies of nature and anthropology docs, cameos from SNL cast members, surreal dream sequences, man-on-the-street interviews, musical performances (including one, from Sid Vicious, that now contains no sound, due to a rights issue), and random—and sometimes stridently unfunny—asides and tangents.

The film’s structure and tone faithfully re-creates the vibe of early Saturday Night Live’s occasional, usually Andy Kaufman-fueled digressions into anti-comedy. But O’Donoghue was doubly hampered in his efforts to make something truly dangerous and edgy, first by the network censors who tamped down his most outlandish impulses, and then by the distributor’s need to pad out a 70-minute show to a full hour and a half. Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video has a couple of highlights, like the scene where O’Donoghue surreptitiously “directs” oblivious passersby on a city street as if he’s making an enormous disaster movie where the special effects keep misfiring. But it mostly set the precedent of stretching good SNL material into meager, lukewarm SNL features that would continue haunt the brand for decades. [MS]

No movie better exemplifies Saturday Night Live in the 1970s than Gilda Live—and not just because the film is essentially a compilation of Gilda Radner’s best SNL sketches, restaged as a theatrical revue. The very existence of Gilda Live has its roots in the clash of egos that raged backstage at SNL as the show became more and more popular. Gilda Live stemmed from Radner’s desire to compete with Chevy Chase, John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, and Bill Murray as they were becoming major movie stars; and the film also had a lot to do with producer Lorne Michaels trying to reclaim ownership of the phenomenon he’d created, before Hollywood made more millions by plundering his talent pool. The problem for Gilda Live—both when it was performed on Broadway in 1979 and when the movie version came out in 1980—is that critics knew about all the behind-the-scenes drama, and savaged Michaels and Radner for serving them leftovers.

Today, those pans seems short-sighted. Now that the Radner-era Saturday Night Live isn’t on TV every week, Gilda Live is a welcome reminder of why Radner was as much of breakout star on SNL as Belushi, and how writer Anne Beatts had as much to do with the early success of the show as her male counterparts Michael O’Donoghue, Al Franken, and Tom Davis. As Radner runs through her most famous characters—hard-of-hearing do-gooder Emily Litella, crass lifestyle reporter Roseanne Roseannadanna, nerdy Lisa Loopner, druggie punk-rocker Candy Slice, and exuberant pre-teen Judy Miller—she assembles a collage-like portrait of the public and private lives of women at the end of the 1970s, making a statement that the sketches couldn’t when sprinkled among the rest of SNL. Plus, she looks to be having a ball doing it.

Thanks in part to veteran stage and screen director Mike Nichols, Gilda Live is tighter than most Saturday Night Live episodes—aside from the interludes where Don Novello’s Father Guido Sarducci or pianist Paul Shaffer vamp while Radner changes for the next sketch. When Shaffer decided to do Gilda Live, Belushi forced him to quit The Blues Brothers; but as good as The Blues Brothers movie is, Shaffer made the right choice. He helped give Radner the showcase she deserved. [NM]

Arguments rage as to which Saturday Night Live movie is best, but there’s no debate as to which Saturday Night Live movie is the biggest. The widely loved The Blues Brothers is an oversized It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World for the dawn of the 1980s, one that found suit-clad, sunglasses-wearing bluesmen Jake (John Belushi) and Elwood (Dan Aykroyd) destroying much of Chicago in a crazed quest to reunite their band for a climactic show that will raise enough money to save the orphanage where they were raised.

Yet while The Blues Brothers had a big budget, a big running time, a big cast, and a big audience, it had a core premise just as slight as most other Saturday Night Live movies. How do you make a movie based on characters who never talk or reveal anything about themselves, other than their love of blues and apparent aversion to bright lights? The solution director John Landis (fresh off the paradigm-shifting success of Animal House) and co-writer Aykroyd came up with was to make the movie a big-hearted, extremely loud valentine to R&B and soul music, largely relegating the Brothers to the background while James Brown, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, John Lee Hooker, and Cab Calloway take center stage in lavish production numbers.

The Blues Brothers is a film of bleary, deliberate excess, a coke-fueled car-crash comedy willing to wait a long time for laughs, particularly in its nearly 150-minute-long director’s cut. But it’s also cinematic and audacious in ways Saturday Night Live movies would never be again. Blame it on the cocaine, but there was a sense, that in the beginning at least, that a Saturday Night Live movie could be anything—a blockbuster, an epic, a deadpan satire on a massive scale. Decades later, the film continues to occupy prime real estate in popular culture [NR]

The first film adaptation of the Mike Myers-created sketch of the same name is the most commercially successful Saturday Night Live-born film in a walk, and one of only two SNL films (the other being The Blues Brothers) that were considered worthy of a sequel. In fact, Wayne’s World was such an unexpected hit—landing in the top 10 highest-grossing films of 1992—that it kicked off a nearly decade-long quest on the part of producer Lorne Michaels to replicate its success, first via a quick-turnaround sequel in 1993, then a string of increasingly ill-conceived SNL-sketch-derived films released at a clip of roughly one per year for the rest of the decade. But none were able to recapture the strange, zeitgeist-y magic of Wayne’s World.

Part of it was timing: “Wayne’s World” was one of of SNL’s most popular recurring sketches in the early 1990s, thanks in large part to the way its format—two slacker rocker dudes (Myers as Wayne Campbell and Dana Carvey as his sidekick, Garth Algar) broadcasting a public-access talk show from a basement in Aurora, Illinois—allowed for incorporation of the show’s weekly special guests, as well as a slew of sorta-catchphrases (“Schwing!,” “...NOT!,” “Party on,” etc.) that instantly entered the popular lexicon. The film version smartly adapts these qualities to the big screen, weaving celebrity cameos and pop-culture references into a plot centered on the compromises involved in taking a small-time endeavor like a public-access show—or, if you will, a late-night comedy sketch—to the big-time. The TV-host aspect of the premise also allowed for the sort of fourth-wall-breaking and self-referentialism, via Wayne’s narration and asides to the camera, that would become increasingly prevalent in mainstream comedy in the coming years. In addition to the film’s enduringly silly quotability (“Actually, it’s pronounced ‘Mil-e-wah-que,’ which is Algonquin for ‘the good land’”), it’s this aspect of Wayne’s World that holds up best today, even as its references and plot specifics look a little moldy for two decades’ remove. [GK]

Billy Crystal was one of the most popular comedians in America when he made his directorial debut with Mr. Saturday Night. As the regular host of the Academy Awards, one of the public faces of Comic Relief, and the star of the box-office smashes When Harry Met Sally and City Slickers (the latter written by his Mr. Saturday Night collaborators Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel), Crystal had found his niche as the likable Baby Boomer who understood the angst of his generation and also adored old-time showbiz. With Mr. Saturday Night, Crystal looked to put his love of barely remembered Jewish comics and the early days of television into the context of one of the mild midlife crisis plots that he’d scored with before. Only Mr. Saturday Night was more about a late-life crisis, with Crystal playing an elderly, sour comedian named Buddy Young Jr. (a character he’d played in a few Saturday Night Live sketches during his one year on the show), trying to keep his career going past its expiration date.

Though undeniably a vanity project—and a commercial flop that marked the end of Crystal’s brief stay on the Hollywood A-list—Mr. Saturday Night is a heartfelt and modestly entertaining film. Mr. Saturday Night works best as an era-hopping look back at comedy in the mid-20th century, as opposed to a drippily earnest study of how one egotistical entertainer alienated his fans, his daughter, and his manager/brother (played by David Paymer, who earned the film’s lone Oscar nomination). The biggest problem with the film is that it tries too hard to be substantive, when really, the simpler scenes of an unsmiling Buddy studying other comics’ acts—and the montages that intertwine Buddy’s major life events and fluctuating career arc—say all that needs to be said about the demands of honing a craft and making it to the top. And they say it well, too. [NM]

There isn’t much to the original 1986 SNL sketch that introduced conservative folk singer Bob Roberts: At a combination book-burning and weenie roast, Bob (Tim Robbins) sits by the campfire with a bunch of chipper whitebread young people (including Chris Farley, David Spade, and Rob Schneider), unironically singing happily racist songs like “God-Fearing, White, And Free.” Six years later, Robbins expanded the character into a grotesque indictment of the American political system: a mockumentary following a similar folksinging character named Bob Roberts through a senatorial campaign based on patriotic button-pushing, lies, innuendo, and ruthless manipulation of the public and the press. It was a name-making directorial debut for Robbins, who also scripted, starred as the title character, and co-wrote the songs with his brother David. It’s also a scathing cautionary tale about buying into slick huckster candidates who push racism and classism buttons, accuse any detractors of being communists, radicals, or atheists, and have no clearly defined political plans, but noticeably precise financial ones.

Like many SNL-derived movies spun out of a single sketch, Bob Roberts doesn’t have to maintain allegiance to any previously built mythology or agenda, and Robbins was free to shape the story as he wanted to see it—in this case, as a bleakly cynical saga that holds up no hope for the American people’s ability to see through a political scam artist, or American journalism’s ability to investigate and expose a fraud. The point-of-view character is a British documentarian (Brian Murray) who takes a patient, exploratory investigative view that few people in the film have; the film ends with him grimly standing alone at the Jefferson Memorial, mirroring a key scene in Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, and like Mr. Smith, wondering what American democracy has come to. He has a mirror in Bob Roberts’ political opponent, a 30-year Senate vet played with lugubrious professionalism by Gore Vidal, largely espousing his own political views, and standing up for social programs and intellectual rigor instead of empty promises and the me-first attitude of Roberts songs like “This Land Is Mine.” (Robbins reportedly scuttled the idea of a soundtrack album because he was afraid the tunes would be turned into real-world, unironic propaganda.)

There’s plenty of entertainment in Bob Roberts. Roberts’ music, which pointedly steals Bob Dylan’s musical style, album titles, song ideas, and music-video iconography, is lively and perniciously catchy, even as it stumps for lynching pot-smokers and suppressing liberal voters. The talented, perfectly selected cast includes Alan Rickman and Ray Wise as Roberts’ right-hand men, Breaking Bad’s Giancarlo Esposito as a wild-eyed muckraker out to expose Roberts, a series of familiar actors (James Spader, Helen Hunt, David Strathairn, Peter Gallagher) in small roles, and John Cusack as the guest of the week on a Saturday Night Live-esque prime-time live comedy show, which hosts Roberts on behalf of its corporate masters. And the faux-doc illusion is impeccable, moving the story along briskly without feeling rushed. But the film isn’t funny, exactly. It creates laughable situations and dark, uncomfortable chuckles, but in its way, it’s more sad and serious than an attempted giggle-fest. Any film where the bad guys win, undisputed and unequivocally, is hard to take as comedy. [TR]

The Coneheads—an alien family living on Earth, barely remarked upon in spite of their flagrantly bizarre appearance and behavior—were a staple of Saturday Night Live from 1977 to 1979. So the 1993 movie felt like a hell of a throwback, with the original Conehead family (Dan Aykroyd and Jane Curtin) dropping right back into their old roles, and the script (co-written by Aykroyd and longtime SNL writer-vets Tom Davis and Bonnie and Terry Turner) pushing them right back to the old gags from 14 years previous: the Coneheads speaking in a flat monotone, eating inedible things (toilet paper, glass cleaner, etc.), and using 10 words where one would do. As a comedy movie, it’s mighty one-note, with most of the jokes being nerdy word humor or just offbeat, “What exactly am I watching here?” sight gags. But it also feels like something out of a different era, when SNL tried harder to be unpredictable and bizarre, and came up with more go-for-broke ideas.

As a story, it’s more sophisticated than most of the SNL crop, and it does much more to soften and humanize its characters, even though they aren’t human. The whole thing functions as a stern lecture about the value and humanity of immigrants, and a vilification of America-first border hardliners. The screenwriters pointedly return over and over to the idea that alien patriarch Beldar Conehead (Aykroyd), in spite of his giant expanding mouth, triple rows of pointy teeth, unsettling notions about personal space, propensity for eating 20 waffles at a sitting, and negligence in causing the crash-landing that stranded the Coneheads on Earth, still makes an outstanding employee and an exceptionally loyal American. He’s diligent, hard-working, and humble, and his only ambitions are to make a good life for his wife Prymatt (Curtain) and daughter Connie (Michelle Burke) in the new world. The whole film follows him on a standard immigrant’s journey as he settles into his new life, competently works a series of jobs, and achieves the American Dream of a nice house, a stable environment, the acceptance of his peers, and a golf trophy. All this, while the INS attempts to hunt his family down.

The film also functions as a somewhat startling Saturday Night Live cast reunion, most notably (apart from the leads) with Michael McKean as the INS agent on the Coneheads case, David Spade as his unctuous toady, and Phil Hartman as Beldar’s alien boss. There’s another familiar face every minute: Jan Hooks, Kevin Nealon, Chris Farley, Ellen DeGeneres, Jon Lovitz, Adam Sandler, Parker Posey, Dave Thomas, Laraine Newman, Sinbad, Garrett Morris, Tim Meadows, Julia Sweeney, Michael Richards, and more. (Plus some only barely familiar faces: Jason Alexander and Drew Carey both look so young, they’re barely recognizable.) And they all appear in such small roles that no one has time to get schticky or wear out their welcome—Sandler even gets to play it straight and serious, while Farley is more sweet than sloppy. Coneheads recycles old business from SNL, sometimes word-for-word, and takes few risks with its comedy, but it does have some technical and narrative ambition, and an admirably inclusive point of view. It’s also appealingly unique. Where else are you going to see Aykroyd in a loincloth, singing “Tainted Love” in a nasal monotone as he lines up a golf drive against a giant scaly monster, stop-motion-animated by Phil Tippett himself? [TR]

As the first, and really only true sequel in the library of SNL films (the years and cast change between the original Blues Brothers and Blues Brothers 2000 render the latter more of a spiritual sequel than a direct one), Wayne’s World 2 had to figure out how to extend an already over-extended premise. The solution wasn’t particularly elegant, saddling the newly successful, ostensibly more mature Wayne (Mike Myers) with a vague desire to find his purpose in life, which ends up being holding a massive rock concert, called WayneStock, in his hometown of Aurora, Illinois. But mostly, Wayne’s World 2 is concerned with trotting out celebrity cameo after celebrity cameo (Drew Barrymore, Charlton Heston, Heather Locklear, Rip Taylor, the sweaty torsos of the members of Aerosmith) and driving its predecessor’s catchphrases into the ground. The script—penned, like the first film, by Myers alongside Bonnie and Terry Turner—also gets routinely sidetracked by a subplot involving Wayne’s girlfriend, Cassandra (Tia Carrere), whose ascendant music career both mirrors the first film’s plot and gives the sequel its villain, music producer Bobby Cahn (Christopher Walken), who fills more or less the same role Rob Lowe’s smarmy TV exec did in the first film.

Wayne’s World 2 is burdened by a tangible flop-sweat as it struggles to re-capture lightning in a bottle. Imbued as it is with the spirit of sketch-comedy, the film has its share of memorable stand-alone sequences, including a brilliantly weird late-movie homage to The Graduate. But success spoiled Wayne’s World, turning its scrappy heroes into world-beaters and giving them lame new challenges to rise above. (Garth’s obscenely sexy new girlfriend, a femme fatale played by Kim Basinger, serves as a perfect personification of this problem.) It’s completely understandable why a Wayne’s World sequel seemed like a good idea in 1993, but the results show that Myers and company should have said “No way!” instead of “Way!” [GK]

Even among one-joke SNL characters who got their own movies, It’s Pat enjoys special notoriety: It was dumped in only 33 theaters, and is the rare studio movie to score a five-figure gross; it didn’t earn a single good review (0% on Rotten Tomatoes); and it almost certainly would have swept the Razzies if it wasn’t Showgirls’ year. Two decades later, the film somehow looks worse than ever, since the endlessly belabored gag of whether Pat (Julia Sweeney) is a man or a woman turns on the repulsion (or psychotic attraction) people feel toward this weird, hostile, snot-nosed androgynous creature. To be fair, It’s Pat intends the opposite message, one of tolerance and open-mindedness, where the hoped-for (and never achieved) resolution to the gender question doesn’t matter. But that’s a tough sell when so much of the movie—and the sketch—is premised on Pat being not a he or a she, but an “it.”

Still, this tortured exercise in stretching “It’s Pat” to feature-length qualification—it comes in at Berlin Alexanderplatz-esque 77 minutes—holds some morbid fascination. There are many peculiar elements to It’s Pat, including Charles Rocket as a WASP-y neighbor whose obsession with Pat recalls Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window, and Dave Foley donning a wig and a dowdy dress as Pat’s love interest. But perhaps the oddest choice is to make Pat, the ostensible hero (or is it heroine?), into a creepy, sniveling narcissist who’s as off-putting on the inside as he/she is on the outside. “Is that a banana in your pocket or are you just happy to see me?” Yes, that is a banana in Pat’s pocket, and there’s nothing in It’s Pat to be happy about. [ST]

Al Franken was nobody’s idea of a movie star. Even when he was yucking it up on Saturday Night Live, it was always easier to imagine him as a future senator than it was to imagine his name beaming down from a cinema marquee. And Stuart Smalley—an effete, painfully self-conscious, aggressively non-threatening 12-step enthusiast and low-level television personality—was no one’s idea of a movie hero. But Franken had a vision for the character that set the film apart from its contemporaries, a vision rooted in part in Franken’s own deep understanding of addiction, co-dependency, and violent familial dysfunction. The caliber of Franken’s collaborators also sets the film apart: The film was director Harold Ramis’ follow-up to Groundhog Day, and co-stars heavyweight thespians Harris Yulin and Vincent D’Onofrio as Smalley’s emotionally abusive, alcoholic father and his alcoholic, pot-smoking, emotionally stunted brother, respectively.

Stuart Saves His Family hits many of the expected Saturday Night Live movie beats. The film introduces Stuart’s friends and co-workers before he’s fired from his public-access show and given a much bigger commercial platform, in a development that echoes the plot of Wayne’s World. But much of the film is devoted to a defiantly bold and non-commercial depiction of the emotional costs wreaked by alcoholism and depression: It climaxes at an intervention for Yulin’s character, and is brave enough to end on a messy, open-ended note, with Smalley reconciling himself to the painful truth that no one can really save their family, and that it’s futile and self-destructive to try. Stuart Saves His Family is surprisingly deep and emotionally satisfying as comedy, but it’s even deeper and more satisfying as a drama. [NR]

If Blues Brothers 2000 accomplishes nothing else—and it arguably doesn’t—it at least proves with absolute finality that John Belushi was an irreplaceable comic talent. In this woeful sequel to the beloved original film, it takes no fewer than three actors—John Goodman, Joe Morton, and J. Evan Bonifant—to fill Belushi’s suit and sunglasses as Dan Aykroyd’s partner in crime and high-energy R&B. Despite the trio’s laudable enthusiasm, they fail to muster even a fraction of Belushi’s brilliance and charm. Admittedly, the cast isn’t as big of a problem as the script, by Aykroyd and director John Landis, which is like a fuzzy, fifth-generation photocopy of the original Blues Brothers. Once again, Elwood Blues (Aykroyd) must put the Blues Brothers’ band back together while staying one step ahead of the cops (led by Morton’s Cab Chamberlain) and a comically ineffective hate group (a white-supremacist militia in the place of the original film’s Illinois Nazis). Once again, the film alternates between highly choreographed musical numbers and highly choreographed car chases.

Landis stages those scenes with aplomb; a YouTube compilation video of just the songs and the pile-ups might trick you into thinking Blues Brothers 2000 is a decent follow-up to its predecessor. But everything else about the sequel is soul-crushingly dire, and the film has absolutely zero forward momentum. In the first Blues Brothers, Belushi’s Jake and Aykroyd’s Elwood have a reason to race around the Midwest in a desperate, law-breaking search for money: They’re trying to save the orphanage where they were raised. This time, Elwood kidnaps a child, evades the police, and incites the Russian mob for no reason whatsoever beyond the fact that he did similar stuff in the first movie, and Aykroyd and Landis figured audiences would want to see him do it again. The plot hinges on the band avoiding the police, the militia, and the mafia long enough to win a Battle Of The Bands, but the contest ends in a draw, and the bad guys from the militia and the Russian mob are all instantly turned into rats by Erykah Badu’s voodoo queen. It’s glib to say the film has all the drama of a bad Saturday Night Live sketch—but it’s also entirely accurate. [MS]

The typical line on feature-length adaptations of SNL sketches is that the sketches are too thin for a movie, but A Night At The Roxbury is a case where the sketch was too thin for a sketch. A “Roxbury Guys” sketch involved the Butabi brothers, Steve (Will Ferrell) and Doug (Chris Kattan), hitting the club scene in rayon suits, bobbing their heads in time to Haddaway’s “What Is Love?”, and striking out with the horrified women they grind up against. It was an easy bit for SNL guests like Jim Carrey, who could get plugged into the scene for a few minutes, but we never heard the Butabis speak and never learned anything about them, other than the one joke that these would-be slicksters handle constant rejection with the same metronomic cluelessness. Doing a movie version of “Roxbury Guys” meant losing the goofy, so-dumb-it’s-funny simplicity of the sketch while adding backstories, subplots, and speaking parts. And who wants that?

For this task, Lorne Michaels turned to producer Amy Heckerling, who brought along some alums from her hit Clueless (Dan Hedaya most prominently) and is perhaps responsible for the sweetness that makes A Night At The Roxbury occasionally disarming. What it isn’t is funny, save for a few scattered moments, like a seduction scene where Doug keeps throwing out pick-up lines even after he’s convinced a woman to sleep with him. (“Do you like blueberries or strawberries?” “Why?” “I want to know what kind of pancakes to order you in the morning.”) Mostly, the film is full of time-wasting measures, like a marriage plot about the future of the Butabi family silk-flower business, references to Cameron Crowe movies, and minor celebrity turns, like Richard Grieco as himself, Loni Anderson as the Butabis’ cosmetically enhanced matriarch, and Chazz Palminteri as a club owner who keeps accusing people of grabbing his ass. Poor Colin Quinn, as Palminteri’s lackey, would like everyone to know that he’s not guilty of that latter charge. [ST]

Molly Shannon’s feature outing as Mary Katherine Gallagher is another SNL Studios product from a period when the show seemed to be creating characters (and featuring them over and over again) with an eye toward movie spin-offs, whether or not they cold sustain a feature-length film. Superstar is a perfect example of why that strategy so rarely worked. Though a break-out character in 1995, Mary Katherine Gallagher—a sexually frustrated Catholic schoolgirl with a love of performing and a tendency to fall down a lot—didn’t exactly have a lot of unexplored layers by 1999. What’s more, the character could get pretty abrasive over the course of a sketch, never mind over the length of a movie. Though it’s directed by Kids In The Hall’s Bruce McCulloch and co-stars Will Ferrell, Superstar’s biggest problem is that it’s almost entirely bereft of laughs. Mary Katherine’s universe gets bigger via an origin story, some new friends, and a job at a video store that gives her ample opportunity to memorize melodramatic monologues, but the character does little beyond the schtick seen on the show. Superstar has the good sense to call it a day after 81 minutes, but those 81 minutes seem much longer. [KP]

Mike Judge’s first foray into animation was a series of shorts collectively called Office Space, about a mumbling office drone named Milton (voiced by Judge) who is hounded by a sleazy boss (Judge again) who swipes his stapler. The shorts were aired on Saturday Night Live, and after Judge found even greater success with Beavis And Butt-head and King Of The Hill, he brought the characters back, this time in live-action form, on the big-screen. The result, 1999’s Office Space, has maybe the most tenuous connection to SNL of any of its spinoff movies—the cast doesn’t include a single Not Ready For Prime Time Player, and Lorne Michaels isn’t a credited producer—which might explain why it’s also one of the best films the series ever produced. Not being beholden to a fan base looking for their favorite catchphrases or characters has its advantages (though not at the box office, where Office Space flopped).

Rather than stretching out Milton’s minuscule struggles for basic human dignity, Judge kept them small, letting them serve as interludes in a larger story about his co-workers at Initech, a company preparing bank software for the Y2K bug. (Kids, ask your parents.) It’s an ingenious way to make a character who previously existed in five-minute chunks work at feature-length. Peter Gibbons (Ron Livingston) is a dissatisfied office drone who hates his job, his life, and his boss (Gary Cole). Things brighten slightly when a hypnotherapist (Mike McShane) suffers a fatal heart attack before he can wake Peter from a trance that’s supposed to help him cope with his frustrations. Suddenly freed from caring about his job (or anything else), Peter dumps his unfaithful girlfriend, strikes up a relationship with the cute waitress at the local chain restaurant (Jennifer Aniston), stops kowtowing to his boss, and plans to exploit the Y2K bug to steal a retirement fund from Initech.

Traditional Saturday Night Live movies trade in absurdity and surrealism, but Office Space’s workplace satire is soul-crushingly mundane, from the madness of paperwork etiquette to the misery of commuting traffic. The results are hysterical—and depressing to anyone who’s suffered similar indignities at the hands of faceless corporations. The combination of brilliant comedy and trenchant social observation make Office Space the modern corporate workplace equivalent of Network, another bleak story about a loser whose mental illness brings him great success in an inhuman working environment that rewards unpredictable, sociopathic behavior. [MS]

The trouble with most SNL adaptations is they stretch a one-joke character to feature-length, but The Ladies Man has the opposite problem: It runs away from the sketch too quickly. Leon Phelps is “The Ladies Man,” a Courvoisier-sipping, incense-burning, 1970s-attired superstud who dispenses romantic advice over the radio, mainly involving the finer points of bedding the easily seduced. While it wouldn’t be terribly cinematic to have Phelps taking calls for 84 minutes, the opening credits are barely over before The Ladies Man kicks Phelps out of the station and sets about reforming this lothario. Beyond a very funny scene in which Phelps briefly lands a job at a Christian radio station and sweats his way through an entendre-filled interview with a nun, the film is out to teach him how to be not a ladies man, but a better man. And that’s deadly for comedy.

Still, there’s a sweetness to The Ladies Man that owes much to its star, Tim Meadows, an SNL journeyman who finally got a breakout character and took him as far as could go (and with this film, too far). Director Reginald Hudlin more or less did the same thing with Eddie Murphy in 1992 comedy Boomerang, but he struggles to squeeze laughs outside of Phelps, despite Will Ferrell’s strenuous efforts as a Greco-Roman wrestling enthusiast who leads a mob of cuckolded husbands against Phelps. Phelps’ personal growth is surprisingly sincere and good-hearted, but any growth at all takes “The Ladies Man” out of The Ladies Man. [ST]

The 1984 SNL sketch that presaged A Mighty Wind had a surprising number of the elements already in place: Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, and Christopher Guest played an aging folk trio called The Folksmen, based heavily on the Kingston Trio, and they sang snatches of most of the songs they’d play as the Folksmen in the feature film. But the 2003 feature doesn’t have the shapeless wandering of the original sketch: It’s the most crafted of Guest’s improv-troupe mock-doc features, with a strong throughline of a plot, and the thoroughly entertaining songs as anchors. Built around a promotional concert that pulls together two legacy folk bands (the Folksmen and the sprawling, painfully wholesome New Main Street Singers, fronted by John Michael Higgins and Jane Lynch) and reunites a third (Eugene Levy and Catherine O’Hara), the film lets Guest’s frequent collaborators poke fun at the folk circuit the way they poked fun at community theater in Waiting For Guffman, and at dog shows in Best In Show. Built via improvisation, then crafted for a tight flow, A Mighty Wind is bouncy and vivid, finding the exceedingly fine line between affection for and merciless skewering of a satirical target.

The real key to A Mighty Wind is the songs. They’re mostly authentic earworms that are nonetheless melodramatic and silly, taking on different problems in folk, from groaning earnestness to affected self-importance. (Don Lake is particularly enjoyable as a corrective to the whole narrative: the son of a famous folk promoter, who can’t entirely escape the business, but finds the whole musical genre painfully tedious.) Guest’s microcosm movies are all enjoyable for the way they dive into a scene and pick it apart, exposing its self-importance and fallacies, but this one is particular fun, and endlessly quotable. It’d be worth watching solely for Fred Willard’s turn as a self-promoting, glib former child star who can’t stop spouting his own catchphrases: “Wha hoppen?” [TR]

Films derived from Saturday Night Live sketches are often, and correctly, accused of being one-joke movies. But these films at least have the consolation of being based on a one-joke premise that has proven successful in one arena. So while the idea of making a movie out of the gender confusion regarding Julia Sweeney’s “Pat” character might seem willfully perverse, at least the character had fans. The same cannot be said of Harold, the luckless star of the perplexing 2008 geriatric teen comedy Harold, from director and former SNL writer T. Sean Shannon. The film’s connection to Saturday Night Live is so obscure that even huge fans of the show might not be aware of its existence. The film was not produced by Lorne Michaels, but its roots can be traced back to a short film shown in the final episode of the show’s 29th season, about a boy named Harold who’s mistaken for a middle-aged man due to extremely early onset baldness.

Harold casts Spencer Breslin as this prematurely aged young person, then puts him through the teen-movie paces as he switches schools after moving to a new town, nurses a crush on a popular girl, tussles with bullies, competes in a big race, and struggles to find acceptance and come of age, all while looking and acting like a 70-year-old Jewish man. Saturday Night Live movies are often criticized for being mercenary and predictable, but Harold’s premise is intriguingly weird, even adventurous, from a conceptual standpoint. Alas, the film itself is dreadful, a sleepily paced non-starter with way too many jokes involving the widespread suspicion that a funky janitor played by Cuba Gooding Jr. is hanging out with Harold so much because he’s molesting him. [NR]

Even by Saturday Night Live film standards, a MacGruber movie was a bizarre proposition. It would be hard to imagine a less timely or hip premise for a 2010 motion picture than satirizing the big hair and convoluted action-hero cheese of Richard Dean Anderson’s gun-averse MacGyver, and a big part of the joke of the character’s appearances on Saturday Night Live was that he was constantly dying due to his own incompetence. MacGruber didn’t even appear in full-length sketches, just bite-sized vignettes. But the Saturday Night Live film machine nevertheless roared back into action to make the biggest and most audacious action-comedy since The Blues Brothers. First-time director Jorma Taccone, who honed his gifts working on digital shorts for Saturday Night Live, perfectly nails the look and feel of chest-beating, testosterone-poisoned 1980s action.

MacGruber could easily pass for what it’s satirizing, except that as played by Will Forte, the title character is less a hero, or even an antihero, than a complete lunatic. He’s a racist, sexist, and grotesquely narcissistic asshole perpetually willing to put the lives of his team in danger for sake of saving money on parking. Even if Forte didn’t spend part of the film naked with a celery stalk in his ass as a diversionary tactic, his performance here qualifies as boldly unselfconscious, and there’s a subversive streak in the film’s depiction of the ultimate 1980s action hero as xenophobic, creepy, and almost as evil as the people he’s fighting. Considering the dated nature of the film’s satirical target, it’s probably not surprising that the film was a huge flop, but has gone on to become a sizable cult hit. [NR]

This concludes our Movie Of The Week discussion of MacGruber. Don’t miss Tuesday’s Keynote on the film’s trajectory from box-office bomb to cult sensation in the making, and Wednesday’s staff forum on the film’s surprisingly slick visual style, its pop-culture references, and its snarky depiction of the modern American hero. Next week, we turn our attention to Steven Soderbergh’s masterful Elmore Leonard adaptation Out Of Sight.