Card #14: “Where’s Luke?”

On Christmas Day, 1977, children across the United States opened up empty boxes—and were happy to have them. Earlier that year, in April, Kenner Products had signed a contract with Lucasfilm and 20th Century Fox to produce a board game based on the movie Star Wars, which was due to hit theaters in May. The additional plan was for Kenner to start manufacturing a line of playsets the following year, by which time the movie would be long gone from theaters, leaving its universe ripe for reinvention as toys. But Star Wars hit bigger than expected, and suddenly anyone with branded merchandise to sell—legitimate or not—rushed to cash in. To get ahead of the bootleggers during the Christmas season, Kenner offered a box containing a certificate that allowed purchasers to mail away for the first four Star Wars action figures, to be released in early 1978.

In Stephen J. Sansweet’s book Star Wars: From Concept To Screen To Collectible, the author/collector writes, “In a way, having little product available in May 1977 probably helped the Star Wars merchandising phenomenon last as long as it did. For true consumer-driven demand, not some false sense of need created by a massive advertising campaign or hype, became what propelled the products.” But that wasn’t a business model that Lucas, Kenner, Fox, or anyone else who stood to make money off Star Wars wanted to follow long term. When the second Star Wars movie, The Empire Strikes Back, was released in 1980, the licensees were ready to capitalize. No empty boxes this time; the goods would be available even before the movie was.

Card #17: New Rebel Strategy

The Topps Company was one of the licensees geared up for The Empire Strikes Back. According to a 1980 trade ad, Topps sold more than 100 million packs of Star Wars trading cards between 1977 and 1980, and well ahead of Empire’s May 21 opening, fans were ready for the next wave of merchandise. Much of the culture and ritual that developed around Star Wars was new to everyone the first time around, from standing in long lines to get tickets to the fun of tearing open a wax Topps package and flipping through the contents quickly, hoping to get “A Horrified Luke Sees His Family Killed” or “Who Will Win The Final Star War?” this time. In 1980, some people were determined to get ahead of the craze by buying Empire Strikes Back cards before seeing the film it was promoting. For many, the movie arrived pre-loved.

Card #77: Warm Welcome For An Old Buddy

The Empire Strikes Back is widely—and rightly—considered the best of the Star Wars films, because it’s the one where the stakes seem the most real, and the outcome most in doubt. Star Wars (or A New Hope, for the pedantic) has an ending. It has a clean arc, with the farmboy hero Luke Skywalker eagerly embracing his destiny and helping land a crippling blow to a tyrannical regime. The Empire Strikes Back is part of a larger story, and was designed as such, so it’s more open and unresolved. Because of that—and because there wasn’t much of a tradition at the time for sequels to be as successful or as high-quality as their predecessors, outside of the James Bond series—some critics were prepared to pounce on Empire when it was released, presuming that audiences would find it an unsatisfying rehash with no conclusion. Instead, the openness proved to be a selling point. Fans followed the patterns they’d established with Star Wars, queuing up to see Empire Strikes Back repeatedly. But this time around, there was an added element of mystery, as fans speculated on what was going to happen next, using some of the more oblique lines of dialogue—preserved on trading cards—as clues.

Card #97: The Fate Of Han Solo

Here’s why The Empire Strikes Back is such a great film: The characters are faced with impossible choices, and sometimes they choose poorly, facing harsh consequences. Luke goes against the advice of his Jedi mentor Yoda and risks slipping over to the dark side of The Force. He loses his hand in the process as he confronts the villain Darth Vader—who turns out to be Luke’s father, who also once turned his back on his Jedi training. Luke’s maverick pal Han Solo takes refuge with old friend Lando Calrissian, who betrays him. Again and again, the good guys screw up. One of the failings of 1983’s Return Of The Jedi is that it insufficiently honors the ramifications of those choices. Jedi sets things right, stubbornly defying the uncertainty that makes Empire so powerful, as well as the notes of despair and darkness introduced by director Irvin Kershner and screenwriters Leigh Brackett and Lawrence Kasdan, working from Lucas’ story.

Here’s why Topps’ Empire Strikes Back trading cards are so important: For a generation of fans and collectors, the Topps cards fixed the images from the film, allowing them to be studied and fetishized. As designers and manufacturers, the Topps team displayed stunning artistry in their various card sets, but rarely with any consistency. Even cards with an eye-catching design, like the 1974 Major League Baseball set, were hampered by uninspired or outright ugly photography, and then redeemed by one stunning action shot. So it went with the Empire Strikes Back cards, where picture after picture of forgettable scenes were outweighed by the a single picture of Han Solo frozen in carbonite, powerful enough to re-conjure all the dread inherent in the original scene.

Card #63: The Secret Of Yoda

This might be hard for the spoiler-averse to believe, but there were kids back in 1980 who knew pretty much the entire story of The Empire Strikes Back before they’d even bought a ticket for the movie. The Marvel Comics adaptation, the Del Rey novelization, and the Topps cards introduced nearly every new character and revealed nearly every major plot point, with the major exception of “Luke, I am your father!” which isn’t mentioned anywhere in the first Topps Empire series. There was some precedent for this with Star Wars. The novelization—ghostwritten by Alan Dean Foster, under Lucas’ name—was published in November 1976, and sold 150,000 copies before the movie opened. But with Empire, fans had a context for the toys, comic books, and trading cards, and just as children expanded the Star Wars universe in their heads after the original movie by collecting the merchandise, some built Empire’s world before they saw it, taking the “Story Digest” on the back of the Topps cards and the pictures on the front and filling in the worlds of Yoda, Lando, and Boba Fett.

Card #22: “But Sir, I Mmh… Mffh…”

Lucas has taken some shots over the years for so aggressively merchandising the Star Wars universe, as though the movies were just commercials for the bedsheets and Halloween costumes. But from the start, Lucas envisioned Star Wars as a more fully realized version of the movie serials and syndicated TV shows he watched as a kid, and a big part of the experience of early fandom was sending away for decoder rings and buying branded plastic guns at the five-and-dime. In Star Wars: From Concept To Screen To Collectible, Lucas is quoted as saying, “My feeling is that if you develop a fantasy world in a movie, it isn’t a particularly bad thing to have kids go home and be able to simulate a fantasy world there and continue to work through whatever emotional needs have been stirred by the film.” The Topps cards didn’t let kids “play Star Wars,” necessarily, but just as they helped burn the images from the film into children’s brains, they also imposed a reassuring orderliness onto those images. One card follows another, like the panels in a comic book, with even the most random-seeming or goofy-looking card serving a purpose in the way it connects to a larger story.

Space Paintings By Ralph McQuarrie: Cloud City

When Star Wars came out in 1977, the special effects appeared so creative and seemingly advanced that a big part of the culture surrounding the film involved a fascination with how Lucas’ team pulled it off. News stories and behind-the-scenes TV specials helped feed the hunger for all things Star Wars, and when the first Empire Strikes Back card set came out, some packs included “Space Paintings By Ralph McQuarrie” cards, showing artwork by the original trilogy’s conceptual artist, whose sketches helped guide the set designers and effects team. Later Empire card sets were filled out with pictures of the movie actually being made. (How many kids out there coveted the “Kershner Directs Mark Hamill” card?) Rather than worrying about demystifying the film and robbing it of its power, Lucas seemed eager to show off a little, and perhaps encourage other young science-fiction/fantasy fans to follow in his footsteps. In the process, he made heroes of men like Ben Burtt, Phil Tippett, and McQuarrie, whose paintings on the Topps cards made the Empire Strikes Back locations look even more dreamlike and fantastical.

Card #38: Joined By Dack

If not for the Kenner toys and Topps cards, would anyone know who IG-88 is? Or R5-D4? Or Squid Head? One of the values of the Star Wars cards was how they directed attention to the weird creatures and minor characters who populated the backgrounds of the series—and gave them names, complete with little “™”s at the end.

Card #64: The Princess Lends A Hand

In Pauline Kael’s mixed review of the first Star Wars, she described Leia as a “high-school-cheerleader princess-in-distress,” and asked, “Is it because the picture is synthesized from the mythology of serials and old comic books that it didn’t occur to anybody that she could get the Force?” (Kael liked The Empire Strikes Back much more, in part because she was a longtime Kershner-booster.) But it’d be a mistake to discount the importance of Carrie Fisher’s feisty portrayal of Princess Leia to the success of the franchise overall—especially on the merchandising end, since Leia allowed Lucasfilms’ partners to market to little girls. With Empire, the addition of Billy Dee Williams’ Lando gave Kenner new inroads into the African-American market. Topps, meanwhile, had the ability to snag anybody who wondered which of their favorite characters might be waiting inside their sealed package.

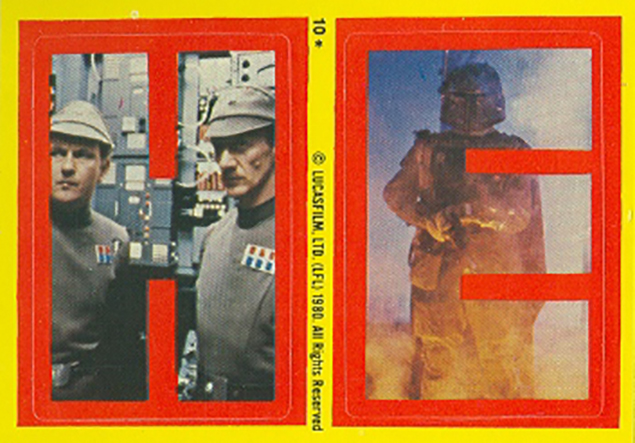

Sticker card: H & E

Each pack of the first Empire Strikes Back trading cards contained 12 cards, a stick of hard, chalky bubble gum, and a floppy card containing one or two stickers, most of which were in the shape of letters, with Empire scenes in those letters’ open spaces. The sticker of choice was the “E” that featured intergalactic bounty hunter Boba Fett, because anything Fett-related was a hot commodity in 1980. First widely introduced in an animated segment of the notorious Star Wars Holiday Special in 1978, Boba Fett became the first Empire Strikes Back toy that Kenner marketed, via a mail-in offer that was delayed briefly when the company decided to disable the action figure’s missile-firing backpack, lest it become a choking hazard. Regardless, even before he’d appeared in a movie, Boba Fett was one of the series’ most popular characters—and though he only appears on a few cards in the first Empire trading card set, he makes an impression, looking cooler than any of the actual heroes do.

Card #87: Host Of Horror

Star Wars: From Concept To Screen To Collectible includes a quote from Charles Lippincott, a USC classmate of Lucas who worked as a publicist on Star Wars and then became the point-man for merchandising deals. In Sansweet’s book, Lippincott says he was troubled by how much clamor there was for the Star Wars villains. (“The little kids went nuts over Darth Vader, and that really caught me off guard.”) In The Empire Strikes Back, though, Darth Vader in particular gains dimensions that make him both more human and more terrifying. It’s no coincidence that Vader’s head adorns the front of every package in all three of Topps’ Empire Strikes Back trading-card sets. Even in card form, Vader is a malevolent figure with an air of tragedy. This can be the dark side of iconography: It allows people to seize on the aspects of the myth that most appeal to them, even if they happen to be the most negative.

Card #132: Checklist: 67-132

If nothing else, the Star Wars trading card series allowed science-fiction fans to join baseball fans in the familiar litany of the card-collector: “Got it, got it, need it, got it… ugh, a checklist card.” But those checklists also had a function, keeping the more driven collectors apprised of what they were missing. (Besides, according to the second checklist card, in order to complete the set, fans needed both checklist cards.)

Card #72: A Need Beyond Reason

It’s difficult to fathom now, but there was a time when the Star Wars sequel was going to be filmed quickly and cheaply, using a lot of the same sets and props as the original in order to recoup some of the investment in overhead on the first film. (Alan Dean Foster’s 1978 novel Splinter Of The Mind’s Eye was originally intended to sketch out the rough outline of what could’ve been.) Star Wars’ record-breaking success changed those plans—as did the ancillaries’ success. Each new toy suggested an expanding story in an expanding universe, which is something The Empire Strikes Back had to live up to. This was the beginning of the love-hate relationship between Lucas and his fans, the latter of whom took what he created and imagined it going places and saying things he’d never intended or thought of. At times, Lucas has seemed to carry these expectations resentfully, as a burden he never asked to shoulder. But that’s just the price he’s had to pay for creating movies so beloved that people want to keep re-experiencing them in myriad ways—even carved up into little pieces and printed on cardboard.